Around the corner from the military medals, the rocking horse, the tea set, a sombrero, assorted arrowheads and the red plastic coin purse emblazoned with “Less fatty in the patty,” here comes Wake Forest Adjunct Lecturer Jan Detter.

“Oh, hi!” she says. “I’m looking for Civil War bullets.”

She will have no luck today in Brookstown Antiques and Collectibles, a favorite musty haunt for the queen of found objects, she who inhabits the world of “both/and,” she who serves as a connector to all she surveys. Detter presses on. A deadline awaits for a project: a female torso encrusted with stones. It will be adorned with a necklace of rusted safety pins and Civil War bullets resting above a pie tin-turned metal heart containing lichen and flax seeds. The concept honors women of that era for the pain they endured as they built strength during a time of loss.

Through a program that pairs an artist with a community leader, Detter and Lee French, CEO of Old Salem Museum and Gardens, will complete the sculpture for an auction to benefit Winston-Salem’s Arts Based Elementary School. It’s a new connection for the pair. “I’ve made a new friend,” French says. His is a common statement about Detter.

Look — and listen — around Winston-Salem. You will see Jan Detter’s shimmering mosaics and African-style memory jugs covered in mortar, then layered with shards of pottery, old glass and recycled objects. You will hear her voice online on StoryLine, where people share stories as a way to build trust across real and perceived racial and class boundaries. You will hear others speak of her. “Community artist,” they will say. “Socially courageous.” “Activist.” “Teacher.” “Mistress of mystery.” “Collaborator par excellence.”

“The students love her,” says Betsy Gatewood, director of the University’s National Science Foundation Partners for Innovation Program who hired Detter as an adjunct lecturer in 2008 to teach classes in social entrepreneurship and creativity and innovation. Gatewood has heard from students “multiple times that she can make that real connection, that she changes people’s lives because she changes their viewpoints and the way they look at the world.”

“The students love her,” says Betsy Gatewood, director of the University’s National Science Foundation Partners for Innovation Program who hired Detter as an adjunct lecturer in 2008 to teach classes in social entrepreneurship and creativity and innovation. Gatewood has heard from students “multiple times that she can make that real connection, that she changes people’s lives because she changes their viewpoints and the way they look at the world.”

Says Bill Conner, faculty director of the University’s Program for Innovation, Creativity and Entrepreneurship: “Every time I see her I just smile.” He acknowledges she does not have the typical academic background of professors at Wake Forest, but “she provides that vital link” between the University and local community. “Entre-preneurial programs really need to be on the edge or they get stale,” he says. “She keeps us edgy.”

At 58 Detter doesn’t look particularly edgy. She stands 5 feet 4 inches tall, sports a sandy brownish bob, displays a taste for flowing clothes and wears rimless spectacles that fall short of screaming artiste. She seems maternal and radiantly approachable. As with most Appalachian foothills gals, spin her a riveting tale and she’s happy. She was born in 1953 in Newton, N.C., and grew up in Maiden, a mill town in Catawba County where her family scratched out a living. Her father worked at the furniture factory. Her mother labored at the glove factory. They gardened to have something to eat, Detter says, not because it was “aesthetically interesting.” Making lard and eating livermush were common pursuits. “Even my scholarship students, they didn’t grow up killing pigs in their backyards. I’ve never found anybody yet that’s had that experience,” she says. Until she went to college at UNC Greensboro, she had never met an artist, never gone to a museum. What she did do was read constantly and yearn “to swim in a new ocean.” As she prepared to enter UNCG, she made her artistic purpose official. “My poor mother began to cry: ‘Here finally, we have someone going off to college, and you’re going to waste it on that!’ ” To her mother’s way of thinking, Detter was supposed to settle down as a Maiden schoolteacher and bear lots of children with whom she would spend lazy summers. Instead, she majored in design with a concentration in textiles, particularly tapestry weaving (“How obscure is that?”) During college she married childhood friend, Dan, a UNC grad who became a toy salesman, and waited until 40 to deliver her first and only child: Zoë. “Nobody in our family believed we had a real job,” Detter says, remembering how she and her late husband used to laugh about their families’ conclusion:” ‘That hippie thing — it ruined them.’” She acknowledges she “did the whole nine organic yards” in her young adulthood and to this day remains someone “into that whole-body thing.”

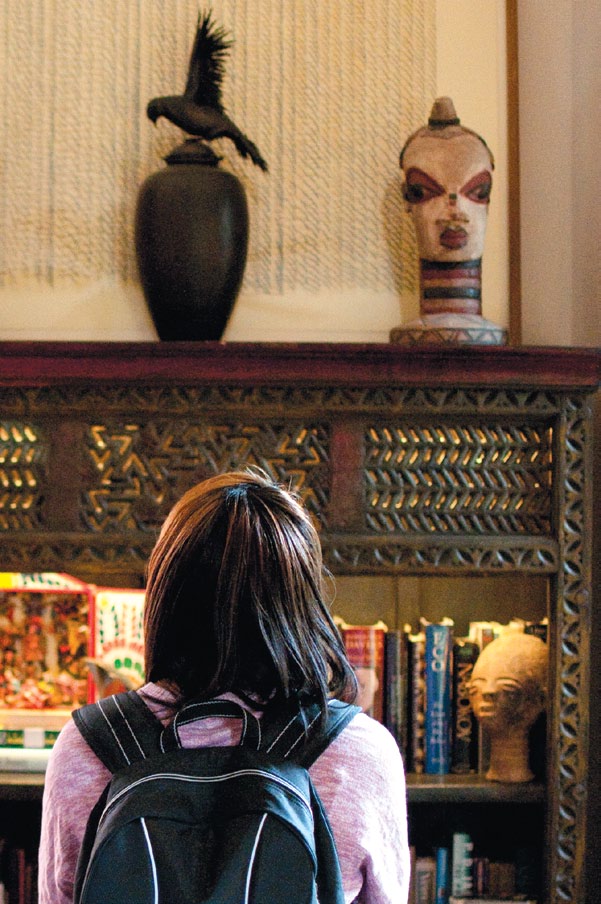

Detter’s Third Eye Studio contains thousands of trinkets, buttons and myriad collectibles that students are free to take for their Storybox projects.

From the time she found her ‘new ocean’ in art, the jobs and community roles Detter accepted constitute a list that goes on for pages, a list that speaks of an artist’s composing a life on her terms — terms that regard art not as a feast for the elite but as part of the societal fabric for all people.

When the city of Burlington, N.C., ranked as a global textile powerhouse, Detter had the good fortune to land her first job after college as the textile artist in residence for the Alamance County Arts Council. It provided an initial taste of teaching and an understanding about the need to connect with community at the deepest and broadest level. One memory: She arrived at a nursing home to expound upon the county’s textile heritage, a lecture that did not assuage residents’ displeasure over their removal from the TV. “Here I come in, slinging my spinning wheel, my yarn, my card and my enthusiasm, and I realized before I even said my first word half of them were dead asleep. I kept thinking, ‘This is good. This is going to be the goal — if you can keep one of them awake until you’re finished you will have done something today’.” Two of the 10 kept their eyes peeled.

Detter, it should be noted, is not afraid to make fun of herself or reveal to her students what she calls her “inner Chicken Little,” which was clucking overtime at the nursing home.

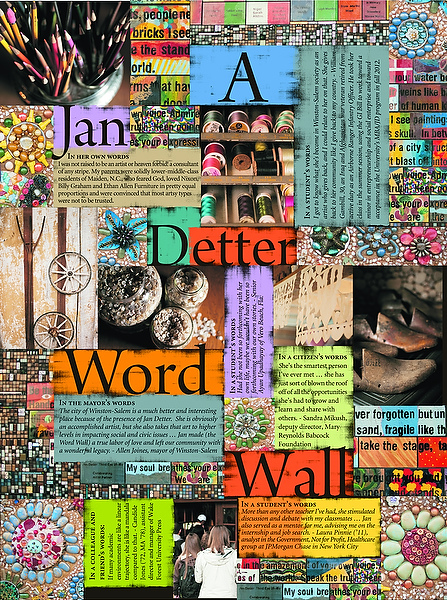

As co-owner of Urban Artifacts in Greensboro in the late ’80s and early ’90s, Detter gained experience as a business entrepreneur, helping prepare her to speak from experience years later to Wake Forest’s would-be entrepreneurs. She has served as executive director of Piedmont Craftsmen; director of the Richmond (Va.) Center for the Visual Arts; and lecturer or resident artist at a long list of venues, from elementary schools to universities, from the Penland School for Crafts to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Her giving back to Winston-Salem ranges from Habitat for Humanity of Forsyth County’s Birdfest (this art auction she founded has funded the construction of 12 houses), to AIDS care, to hospice, to the Humane Society of Forsyth County, to groups working to improve social capital in the city, to the library, to elementary schools and to Authoring Action, whose young people, with her supervision and artistry, completed a “Word Wall” outside Breakfast of Course (Mary’s Too!) restaurant on Trade Street last summer.

Detter’s sum is the combination of all the working parts in her life, the seen and the unseen, and this is her gift to her students. “I exist in community and I work in comm-unity, and because that is so important to me my work is tied up in that. I can’t do one without the other. It’s both/and.”

From the semester’s first days, she tries to convey this outlook of going deep and finding connections. It’s not about doing all that’s expected, she tells students; it’s about looking inside and making sure if one does what’s expected “it’s what you really want to do.” She agrees with other artists who write that humanity finds itself beyond the information age. She says we are now in the conceptual age, where “boundary-hopping” prevails and where the mastery of a single discipline and “binary thinking” about “an either/or world” no longer suffice to serve us. “To be in the conceptual age is to be a synthesizer,” she says.

“Art isn’t about the object you make. I think art is about the object that imbues what life has taught you,” Detter says.

Perhaps above all, her lessons are about story. To her story provides depth, context and connection. Without story, the words are simply information “all dressed up with no place to go.” Detter teaches through her own stories, having come to appreciate the lessons from her childhood in a tight-knit mill town. “My artistic journey began here after all,” she will say.

Students — and Detter herself — regard the seminal event in Detter’s classes as the Storybox project. What objects can students bring in a box to show classmates and tell them a story that could teach the class something about themselves and “perhaps teach you something about yourself that you didn’t know until you told the story?” The assignment unsettles many at first. Detter knows she is asking them to be vulnerable in front of their peers, to “do a radical thing.” So as a gesture of solidarity and fair exchange, she first offers them her own experience — of pain and suffering of the hardest kind. It is the story of how she watched helplessly as her husband, who had been her friend since age 13, lose his fight against melanoma. He died in 2005.

The grief was debilitating. For four years Detter wanted to create a sculpture to honor his memory but could not bring herself to start. It wasn’t until North Carolina filmmaker Cara Hagan asked to shoot her working in her studio that she gathered the courage to begin. The students see the result, “Art for the Living,” including the documentary’s poignant moment when Detter begins crafting the sculpture but is overcome and must leave the room to vomit. “Confronting our discomfort zones is how we learn,” Detter has said.

Lest the exercise sound like a glorified show-and-tell, students regard it as anything but. They treat it with seriousness and say it has led to an openness and closeness among classmates unique to these classes. The Storybox project, they say, teaches them how to sell an idea by giving them confidence in their own story and provides a laboratory for empathy and discovery.

“You’re selling not only what you’re holding; you’re selling yourself,” says freshman Stephen Steehler of Erie, Pa. Ayan Upadhyay (’12) recalls classmate William Gambill’s story in 2011 summer school about a mortar attack in Iraq that blinded a friend and fellow soldier. Gambill’s mementos included a Ranger badge delivered to class in a diaper box signifying that Gambill, now 30, was the father of an infant daughter. Upadhyay says he struggled with his own box until he realized he could “go back and say ‘What did you learn?’ ” about a car accident two years before that caused him to drop out of college until he healed and learned to walk again. One of the items in his Storybox was the old leg brace. Among the many lessons he gleaned from the class: “Just because something bad happens there can be redeeming value to it, and that’s something that I had never fully explored.”

Says senior Daniel Richard, “I really dug down deep and found out what I wanted to do with my life, and it came from her course.” (His goal is to open “a full production art gallery, (with) eclectic organic cuisine and a venue where live performances of notable artists are a regularity” on the Shinnecock Native American Reservation in Southampton, N.Y., where he grew up.) In Los Angeles, Cameron Stephens (‘10) works as a production assistant at Sony Pictures Image Works and plays guitar in two different bands. “I took her class when all these feelings for me that I wanted to pursue were coming to a head. She gave me a book to read about a guy and his guitar and a collection of stories.” He had played guitar only five months when he began Detter’s class and “she tried to get me to embrace that … I ended up writing a song for her class.”

Kitty Amos, retired dean of the divinity school, was the first academic who invited Detter to teach at Wake Forest, in 2002. Despite her “inner Chicken Little” clucking its loudest against the notion because the call was to teach among many distinguished Ph.Ds, Detter finally agreed. Through 2004, she taught spirituality and art, to Amos’ and students’ delight. “She is to me the best of the best,” Amos says. “She is a transformational entity. She transforms people and does it in a way that makes them happy and wanting to be transformed.”

It was Amos whom Detter called in excitement one day by her discovery of a new word in Manhattan at the Paraclete Book Center. “A Paraclete urges us on to evolve, to develop and to become more enlightened,” Detter says, “someone who urges us on toward our larger self.”

Ever since, Detter has set her sights on that word and its fruits. “That’s what I try to be in my class,” she says, “a Paraclete.”

And for the many who know her good works in community, the artist’s efforts don’t stop at the classroom door. After all, for Jan Detter, ours is forevermore a “both/and” world.

FROM THE SYLLABUS: {“Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation” by Steven Johnson {“Out of Our Minds: Learning to Be Creative” by Ken Robinson {“A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future” by Daniel Pink {Jill Bolte Taylor’s talk “My Stroke of Insight” at TED.com {Parker Palmer on “the shadow side of leadership” {Field trip to the Platinum-level LEED-certified Proximity Hotel in Greensboro, N.C., “greenest hotel in the USA”