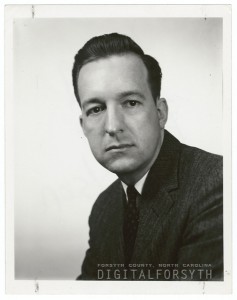

Provost Emeritus Ed Wilson (’43) harks back to his student days on the Old Campus, some 70 years ago, for his favorite Wake Forest memory. It was a cool night in late January; Wake Forest had just defeated N.C. State in a raucous Gore Gym. Walking across the quiet campus, he thought, “Wouldn’t it be wonderful to spend my life here?”

And, thankfully, he did. He shared that story with a group of freshmen last semester in a seminar on the History of Wake Forest taught by Jenny Puckett (’71). It was a quintessential Wilsonian story that had nothing to do with how he affected Wake Forest but how Wake Forest affected him.

Then Wilson told the students his worst Wake Forest moment. After graduating in 1943, he served in the Navy for three years, part of that time as executive officer aboard the USS Raymond (DE-341), a destroyer escort. In March 1946, after the USS Raymond returned from the Pacific theatre to California, Lt. (j.g.) Wilson picked up a newspaper in San Diego. The news was so startling it had made its way across the continent: a small college in a little town called Wake Forest, N.C., was moving across the state to Winston-Salem. He was heartbroken, far from a place held dear.

A young Ed Wilson ('43): Recalling his best — and worst — Wake Forest memories. (Digital Forsyth Archive)

A few months later, Wilson was discharged from the Navy and he returned to his family’s home in Eden, N.C. He planned to attend graduate school until English Professor Broadus Jones invited him back to the Old Campus to teach English. He stayed only one year before leaving for Harvard for graduate school, but he returned in 1951, never to leave again.

When the move to Winston-Salem finally happened in 1956, Wilson brought to the new campus the heritage and traditions of the Old Campus. He had found his home again, albeit in a new place. And since then his personal history and Wake Forest’s history have been intertwined.

Which is why Jenny Puckett invited him to speak to her class on Wake Forest’s history from the 1920s to the 1980s. Puckett, who teaches Spanish at Wake Forest, is passionate about telling the Wake Forest story to students. She’s following in the footsteps of those who passed on the story to her — Wilson, as well as retired history professor Ed Hendricks and the late Bynum Shaw (’48), professor of journalism.

Jenny Puckett ('71) with the Wait Chapel cornerstone: She's on a mission to tell the Wake Forest story.

As she notes, students today come from all over the country, so they aren’t as familiar with Wake Forest’s history as earlier generations were. She wants them to know the stories of the presidents, professors, students and alumni who came before them who built what they now embrace.

She teaches them about William Louis Poteat, who risked his presidency in the 1920s to defend the teaching of evolution and preserve Wake Forest’s academic freedom. She tells them about President Thurman Kitchin, who ensured the college’s survival in the 1940s. With enrollment plummeting during World War II, the college admitted women for the first time and turned over much of the campus to the Army Finance School.

She shares stories about President Harold Tribble that she discovered while writing a biography about him last year. He was an early advocate for civil rights; as a young professor at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, he was often a lone voice speaking out against the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. Tribble’s father was president of a financially struggling college in Florida that eventually closed. She asks students to consider what effect that might have had on his unwavering determination to raise money to move the college to Winston-Salem.

To help her students better imagine the controversy and passionate feelings surrounding the move, she posed this hypothetical question: Should Wake Forest accept Bill Gates’ $5 billion offer to move Wake Forest to Atlanta? How would they feel if “their” Wake Forest moved to another city? A lively debate erupted.

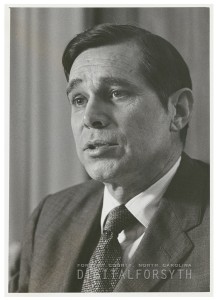

James Ralph Scales expanded arts programs and opened study-abroad houses in Venice and London during his tenure from 1967 to 1983. (Digital Forsyth Archive)

Students were fascinated to learn that their predecessors had once burned Tribble and his successor, James Ralph Scales, in effigy. But the causes couldn’t have been more different. For Tribble, it was over the widely held belief that he was de-emphasizing athletics (despite his having helped establish the ACC and having taken considerable heat for allowing the baseball team to play on a Sunday on the way to the 1955 national championship). The anti-Tribble rally fizzled when cries of “panty raid” swept through the largely male crowd.

In the late 1960s, 600 students marched up Wake Forest Road to the President’s House (now Starling Hall) to protest the Vietnam War. They presented Scales with a list of demands, including the cancellation of final exams and the end of the ROTC program. He told the students he was disappointed in their behavior and he rejected their pleas. They soon lost interest and returned to campus.

A number of alumni shared their personal stories with the students. Byrd Barnette Tribble (’54) revealed the shocking Perfume Bottle Scandal; the bottles actually contained alcohol! From Herb Appenzeller (’48), they learned that he and his football teammates weren’t really keen on playing in the 1948 Gator Bowl — until they learned they’d get a $100 stipend.

The arch on Hearn Plaza, a replica of the arch on the Old Campus, pays tribute to Wake Forest's founding in 1834 and the move to Winston-Salem in 1956.

Mike Ford (’72) described how he arrived for his first day at Wake Forest in a coat and tie, with a suitcase, a small chest, a garment bag and a tennis racket. That was it. The son of the future President of the United States didn’t need a U-Haul to haul his worldly possessions to college.

Students began to tie together the threads connecting the present and the past when former basketball star Randolph Childress (’95) described the influence of biology Professor Herman Eure (Ph.D. ’74). In turn, Eure talked about the influence of Ed Wilson and former Dean of the College Tom Mullen. Childress, who recently returned to campus as an assistant to Director of Athletics Ron Wellman, is poised to continue the pay-it-forward role with the student-athletes he is now mentoring.

Puckett’s students learned the compelling stories behind the names of campus buildings. They climbed to the top of the Wait Chapel bell tower to look down on Jens Larson’s brilliant axis plan for the campus — anchored by Pilot Mountain to the north (representing God and nature) and the Reynolds Building in downtown Winston-Salem to the south (representing man), placing Wake Forest squarely in the middle in the best of Pro Humanitate.

As Puckett is quick to point out, she’s not a historian. She’s just someone who loves Wake Forest. In that sense, she’s just like all of us who love Wake Forest and want to pass the story on to the next generation. As she tells her students, they’re now writing the next chapter in that story. Who knows what the next chapter will bring?

For more on Wake Forest’s history, see Puckett’s “Fit for Battle: The Story of Wake Forest’s Harold W. Tribble;” “Wake Forest University School of Law” by J. Edwin Hendricks; and the series of Wake Forest history volumes by Ed Wilson (’43), Bynum Shaw (’48) and G.W. Paschal (’27).