Tom Hayes’ (’79) documentary film about his late father, famed Esquire editor Harold T.P. Hayes (’48, L.H.D. ’89) — “Smiling Through the Apocalypse: Esquire in the 60s” — premiered in New York City and Los Angeles in September; upcoming shows include Oct. 13 at the Gateway Film Cinema in Columbus, Ohio, and Nov. 10 at the Acadiana Center for the Arts in Lafayette, Louisiana.

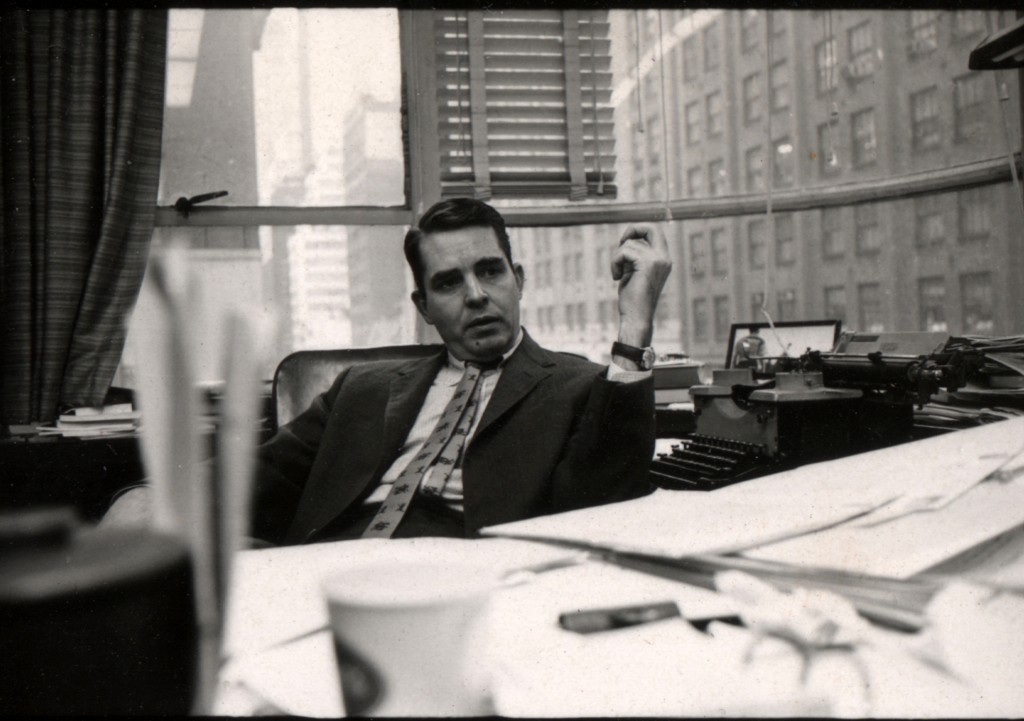

“For me, he was simply dad; to the rest of the country he was Harold Hayes, editor of Esquire magazine,” Tom Hayes says in the film. “I embarked on a journey to find out what made him become what some have said was the greatest post-war magazine editor ever.” Harold Hayes, who died in 1989, was editor of Esquire from 1963 – 1973. He was named to the Wake Forest Writers Hall of Fame in 2012. Tom Hayes talks about his father’s legacy, Gore Vidal and Hugh Hefner, and the never-published Esquire cover that revealed too much of Jack Nicholson.

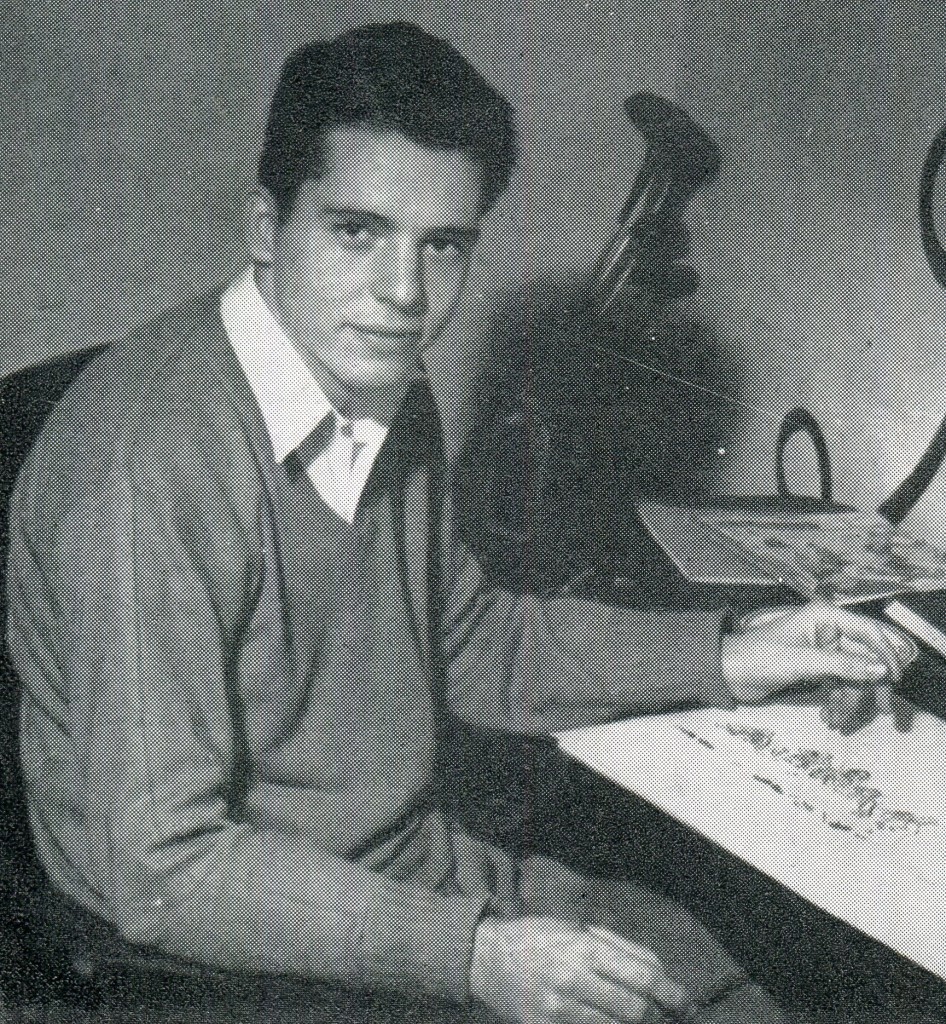

A sign of things to come: Harold Hayes revamped The Student magazine, combining strong writing, creative photography and original artwork to create what the North Carolina Collegiate Press Association called the best all-around magazine in the state.

Your dad was editor of The Student magazine when he was a student on the Old Campus. How did a small, conservative, very traditional, Baptist college influence your dad?

As the son of a North Carolina Baptist minister, Dad had already been brought up in a very conservative, traditional and religious environment. Attending Wake Forest College was an extension of this environment, and his natural exuberant irreverence didn’t have to push the envelope terribly far to begin finding his own voice.

Your dad’s personal papers are in the Z. Smith Reynolds Library. You’ve called it a “treasure trove” of material; what are some of the most interesting items in the collection?

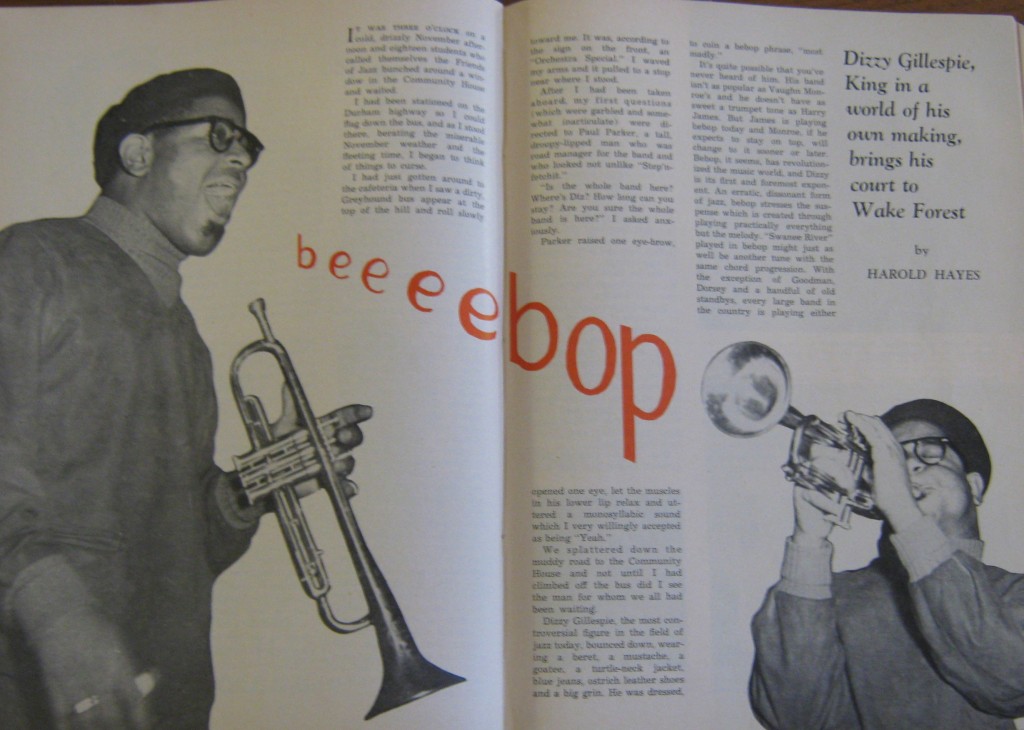

As a Wake Forest student, Harold Hayes flagged down Dizzy Gillespie’s tour bus and convinced him to perform an impromptu concert for students; he later wrote about it for The Student.

Other than my 10th grade report card, there are amazing letters and telegrams between my father and Dorothy Parker, Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Norman Mailer, Richard Nixon and Groucho Marx. One of my favorites is (from) Groucho complaining about the size of the type used in Esquire, and threatening to change his subscription to Playboy where seeing content was less of a challenge.

What compelled you to make a film about your dad some 20+ years after he died?

It was a combination of reasons. The first was not having a tombstone for him anywhere. When he died in 1989, I spread his ashes by helicopter over the wildebeest migration in Kenya, which was his favorite site on earth. Another factor had to do with my mother passing in 2007. At that time, I put together an audio/visual tribute to her which has been parked on YouTube ever since (search “Suzette Hayes”). It was one of the most meaningful projects I ever produced, and it seemed only fitting to do something similar for my father. But what really got me going was a 19-page tribute in a 2007 edition of Vanity Fair Magazine. I thought, who gets that after being gone for 18 years! What had I missed?

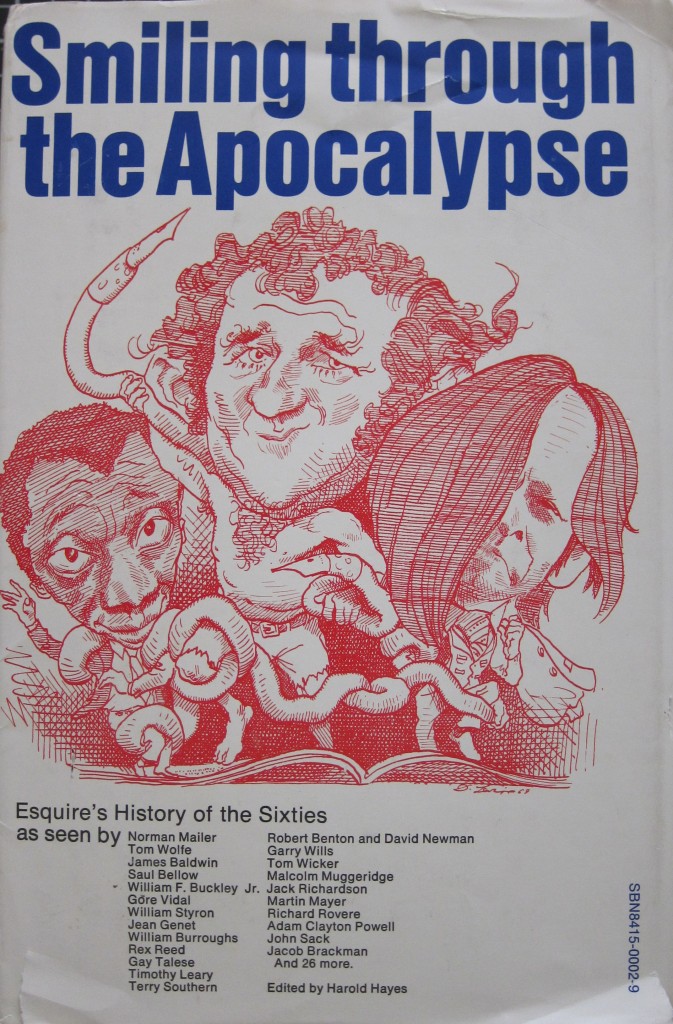

The name of your film actually came from your dad and Esquire’s review of the 1960s, “Smiling through the Apocalypse: Esquire’s History of the Sixties,” published in 1969. Were your dad and the ’60s made for each other?

I would say he had everything going against him to interpret the havoc of this fast-moving decade of change. The magazine was low-budget, had impossible lead times to be current, was not permitted to publish nude women or profanity, paid their writers poorly, didn’t cover pop music, and was forced to cater to advertiser requirements in their fashion pages and classical music columns. All of these obstacles promoted innovation, and may have been similar to the obstacles Dad faced in making The Student magazine provocative and still tasteful at Wake.

I would say he had everything going against him to interpret the havoc of this fast-moving decade of change. The magazine was low-budget, had impossible lead times to be current, was not permitted to publish nude women or profanity, paid their writers poorly, didn’t cover pop music, and was forced to cater to advertiser requirements in their fashion pages and classical music columns. All of these obstacles promoted innovation, and may have been similar to the obstacles Dad faced in making The Student magazine provocative and still tasteful at Wake.

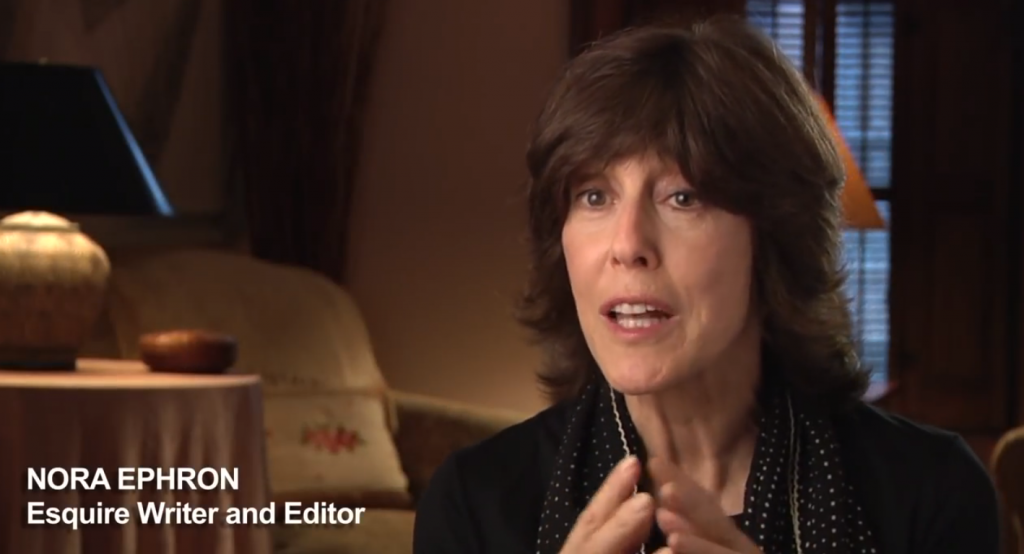

A unique voice and attitude had to be developed that would raise eyebrows, and in turn readership. Certainly the editorial risks he took did not happen without consequence … But for whatever advertiser or management peril he faced, it was the integrity of the writers’ voice that was paramount, and he would go to any length to defend their craft. This is why he attracted so much talent. Everyone knew they could explore and develop their voice under him, and feel safe. As Nora Ephron put it, “It was an absolutely unfiltered you.” This is also why so many people consider their best work was published by him at Esquire.

You were very young when your dad was editor of Esquire. What did you learn about him?

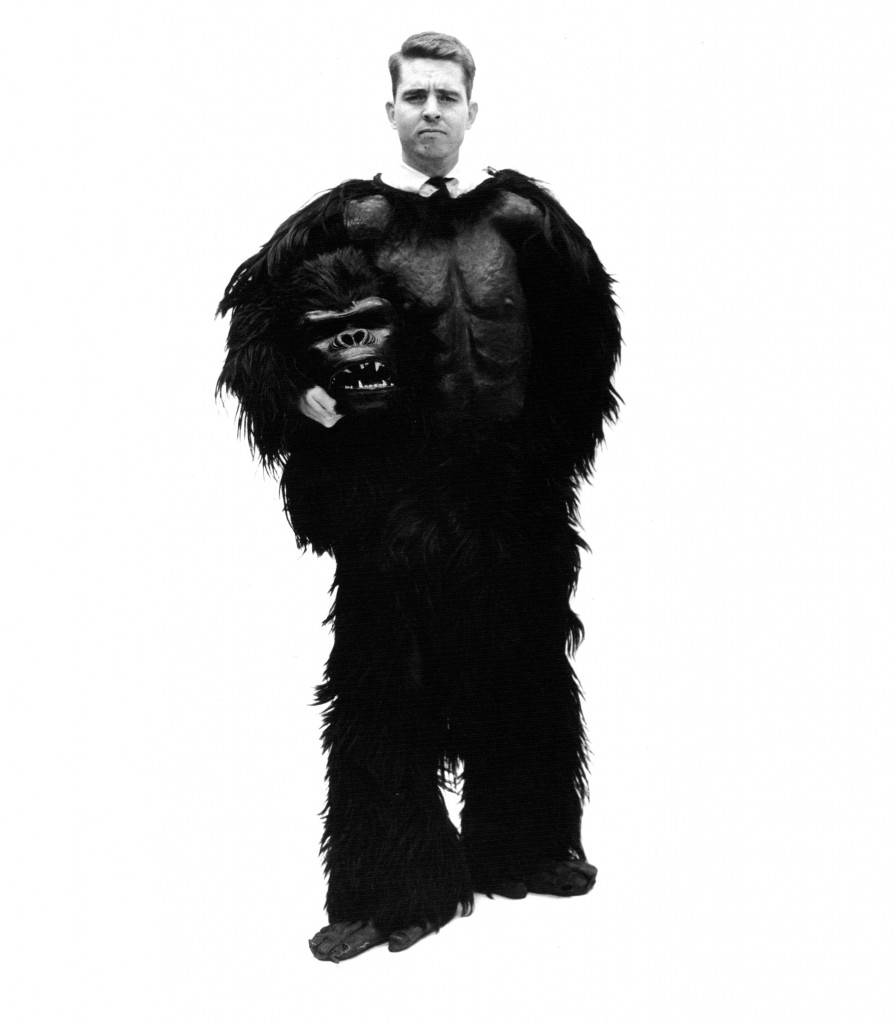

I suppose what I learned most, and quite frankly, am still learning, is how he would look at something, and put a spin on it that would be so completely outside the box. I think this was around us all the time at home, and we just didn’t see it as anything unusual. It was the kind of sensibility where anything obvious or conventional was boring, and only became interesting if you looked past what everyone else was seeing, and tilted it on a specific angle. It certainly didn’t make me any more popular at school and was something I found myself gripping to understand.

Making this film permitted me to go deeper inside my father’s head and get a better understanding about the editorial he published, which made an impression on me as a child, but always on a level of understanding I could never access. I got to understand the dynamics of his thinking and how his brilliance was able to overcome the obstacles he faced in a monthly magazine trying to not only keep up with the times, but also to stay ahead.

I suppose the most surprising thing I learned about him was that he wasn’t perfect. I think many people look up to their parents as models of how you’re supposed to behave, think and act in any situation. Tom Wolfe told me, “Parents should never show their weaknesses.” I got to see a side of my father that humanized him, learning not just about his weaknesses, but also his vulnerabilities. I think this side of him caused me to know him better as a total person, than just as a father.

Your dad nurtured many young writers who went on to become literary giants; can you tell us about some of those you interviewed for the film?

Each interview was special, and many times I was ill-prepared, because I didn’t have a clue as to what I would learn. One of the first was flying to LA to interview Gore Vidal. He wanted me to arrive and then give him a call to arrange the time, but as he said, “not too far in advance, otherwise I won’t do the interview.” Peter Bogdanovich, who’s been a family friend since I was five, knew him and had arranged for his cooperation, which finally led to an invitation to his home in Beverly Hills. I was not prepared for his frankness about his legendary feud with William F. Buckley Jr. or some of the other memories he shared. But he was, as my father had observed, an intimidating person, somehow “tinged with condescension” yet extraordinarily brilliant. Once back in New York, I found it extremely difficult editing around his storytelling and the Scotch he nursed that morning. Nevertheless, I was very fortunate to have interviewed him before his passing.

Nora Ephron was also an interesting encounter. She was actually listed in the telephone directory, which prompted me to call and simply leave her a message on her answering machine. She responded through her assistant to let me know she had about 20 minutes of material and would schedule a time during her publicity campaign for her soon to be released movie, “Julie and Julia,” so that I wouldn’t have to pay for hair and makeup.

The day came and we (my cameraperson and I) were given an address to wait outside on the stoop, and wait for a text message to ring the doorbell. The text came, and we found ourselves in the middle of another interview with her, which was about David Geffen for the PBS Series “American Masters.” Since the 10-person production crew was just breaking for lunch, we were invited to use their setup for our 20 minutes with Nora. We slipped our camera onto their tripod, turned on their lights, and suddenly she was glowing about my father and Esquire in that time. I had never heard such admiration or praise for him in the way she spoke. It turned out to be one of the best interviews … and we were very lucky to get her when we did.

I was the first to interview Hugh Hefner exclusively about Esquire. He had started with Esquire in 1951, but left when the company moved to New York when they wouldn’t give him a $5 raise. I had interviewed him for another project in 1995, and he wore exactly the same red pajamas as he wore then, and it was also in the exact same room. As it turned out, he documented me documenting him by having an in-house cameraman shoot our interview, which would be added to his extensive Playboy archive. He was incredibly vivid in his memories of that time, and very generous with his time. He even tweeted me after I left.

In the film, you describe Esquire as “the red-hot center of journalism … irreverent, brash, fearless … rich with attitude.” What was the magic of Esquire and “new journalism”?

The magic of Esquire was its ability to embrace almost anything. It was the magazine that could be counted on to publish the unexpected. Tom Wolfe commented, “I remember when there was a 5-6 page spread about Chickens!” Articles from the absurd to pivotal articles by leading literary stars could be counted on in every issue. Experimentation was the norm, and satire was the undercurrent. To get around the problem of long lead times to report on current affairs, Dad encouraged his writers to report from the sidelines and employ novelistic techniques such as lots of dialogue, vivid scene setting, character description and interior monologue. Although Tom Wolfe is responsible for identifying the components of New Journalism and credits Pete Hammill for first using the term, my father believed it was a false category that always existed as literary journalism, and can be noticed as far back as Charles Dickens and Mark Twain.

What was Harold Hayes, the dad, like?

Although he worked hard, he did his best to spend quality time with my sister and me. He would go out of his way to give us meaningful experiences, and share with us what he enjoyed, from old movies to canoeing trips to Handel’s “Messiah” sing-alongs. He had this amazing ability to find value in many things others would quickly write off, and a boundless curiosity that showed there was always a different way to look at something. I think this is what he preached at home, and was certainly what helped make his magazine.

One reviewer praised the film as a “memorable time capsule for those who miss the smart magazines that will never return.” Is there any magazine today that comes close to Esquire in its prime?

You have to remember media at that time consisted of three national TV networks, the press, a couple of weekly news magazines, and then a dozen oversized general and specific interest monthly magazines. It was much easier for a magazine like Esquire to stand out then. I don’t think any magazine today stands out like Esquire did in those days.

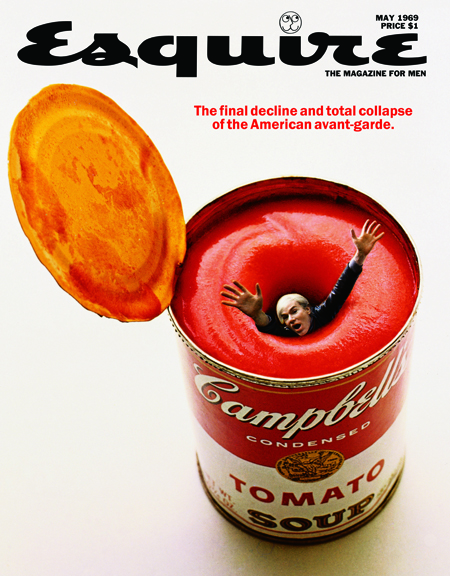

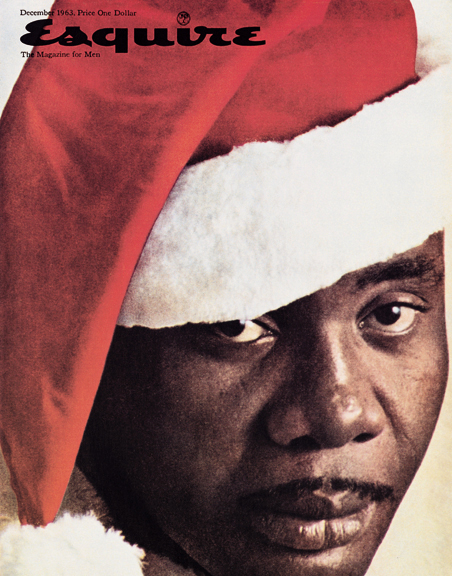

Esquire was known for its provocative covers designed by George Lois; what’s your favorite?

I’m not sure if I have a favorite, because they’re all good. The best ones are those without cover lines, where the graphic says it all. Certainly Sonny Liston with a Santa Claus hat is a favorite, and was also pivotal for my father’s career in that it was the first issue where he was Editor in Chief.

But there are also other favorites like “Oh My God, We Hit a Little Girl!” Muhammad Ali as St. Sebastian, and Andy Warhol drowning in a Campbell’s Soup can.

There’s also one that was never published showing Jack Nicholson sitting nude by the poolside. It was never published because Jack’s manager thought it was tasteless and paid a tidy sum to have it pulled. Peter Bogdanovich called Jack on my behalf to see if he would be interviewed, but Jack declined saying “if it was pulled then, it should probably remain buried.”