I met a man once in a nursing home in Florida who was complaining about the state's "boring" terrain. He had moved from somewhere up north because someone told him it was the place he needed to be. The flatness and monotonous green he saw from the highway on his way down turned him off.

Though mobile and healthy, he hadn’t been out much since. Yet just across the road from that nursing home was a postcard-worthy, cypress-lined haven called Turkey Creek. A baby manatee once swam up to my kayak while I was paddling there with my son.

No, he told me, he hadn’t been there — too much trouble and too many bugs. I couldn’t persuade him otherwise. I needed a way to show him what he was missing, because Florida, where I was born and raised, is far more than what you see from highways. One of the state’s handicaps, in a sense, is its lack of altitude. Wide views are rare, so you see Florida’s beauty in pieces, but sometimes you have to do a little work. I walked away and never saw the man again.

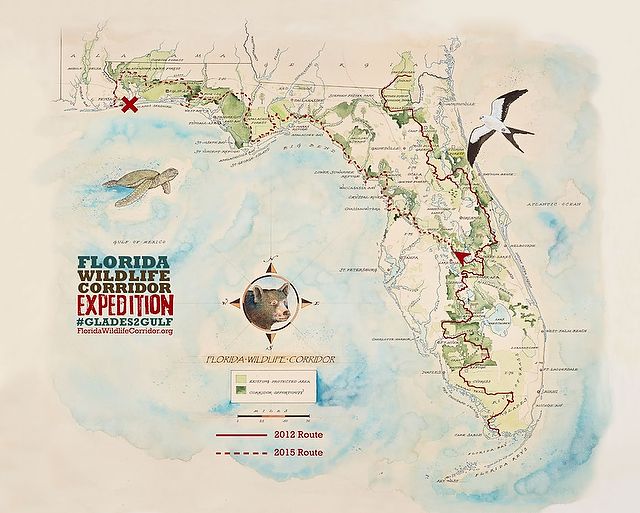

Carlton Ward Jr. and biologist Joseph Guthrie set out by foot, bike, kayak and horse on the first Florida Wildlife Corridor Expedition in 2012. On the Shark River Slough, Ward had a camera on the front of his kayak to take this photograph.

Carlton Ward Jr. (’98), a conservation photographer helping to define the profession, has met plenty of people like that man. But he’s not willing to walk away. For about a decade now he has been hiking, biking, kayaking, swimming and horseback riding throughout the state in an effort to help preserve what’s sometimes referred to as the Real Florida — something far removed from the weird human behavior for which the state has, of late, become famous.

Ward, along with colleagues, recently finished the second of two 1,000-mile expeditions by land and water up and across the state, the latest in a lifetime of adventures. His ongoing goal is to capture images and stories that reveal Florida’s wilderness to the masses in hopes of encouraging protection and inspiring connections to the land where seven previous generations of his family grew up exploring and working.

Ward’s efforts have taken on new significance, as current political and public battles will determine the fate of huge swaths of Florida land that researchers say are critical to wildlife and waterway protection. “I’m really trying to showcase and celebrate the Florida that’s hiding in plain sight to the 20 million people living here,” says Ward. “You don’t know it’s there unless you get out of the car, or out in the water.”

Suburbs to woods and back

Ward grew up in Clearwater, a heavily populated area on the state’s west coast. His great-grandfather, Doyle Carlton, was born 90 miles away in the still-tiny town of Wauchula. That was in 1885, and he went on to become governor during the Great Depression. As governor he cut his own salary, turned down bribes and stood up to Al Capone, who had just moved to the Miami area. Not surprisingly, after all that, he was ready to return to a quieter life in Wauchula, where he bought up land for $2 an acre. Ward’s great-uncle would later expand the family’s ranch in what’s known as the Peace River Valley.

Growing up, Ward visited the historic ranch multiple times a year to celebrate holidays, ride horses, grab oranges and hunt. Every year his dad and uncle hosted a Boy Scout campout on the land — fond memories from Ward’s path to becoming an Eagle Scout and an adventurer.

Today, the land has been split between different families. Several of Ward’s cousins ranch their pieces fulltime, and Ward owns his own small section. “I grew up in the suburbs, but I had one foot in the woods,” he says. “I think that really influenced my appreciation of rural and natural lands and also heightened my sense of urgency for how fast it can disappear.”

Most Floridians don’t get to see the state in the ways that have so inspired Ward. This is in part because most of Florida’s residents, like the man in the nursing home, have come from somewhere else. The populous can be especially unaware of surroundings beyond cityscapes or theme parks — so much so that even residents assume many of Ward’s photos must be from another state, or another continent. Ward shows them what they have been missing.

Physics or the law?

Despite his family history and his quest, there was a time when expeditions and conservation efforts would have seemed an unlikely career choice for Ward. When he arrived at Wake Forest in 1994, he planned to study physics and then move on to graduate school in engineering, or possibly law.

With its longleaf pines, The Nature Conservancy’s Disney Wilderness Preserve, near Kissimmee, serves as a gateway to the Northern Everglades.

But liberal arts requirements pushed him into a biology class, which he loved. Later, in an anthropology course with Professor J. Ned Woodall (P ’99), he learned a lesson that he says more than anything drove him toward conservation as a profession. “I remember in that class really for the first time understanding the story of people and the planet,” says Ward, “and in doing so really becoming concerned about sustainability, and really questioning some of my built-in notions of progress and all that.”

He ended up with a biology degree, and minors in anthropology and environmental studies. As importantly, he was becoming an accomplished photographer, working for the Old Gold & Black and The Howler. Photography also played heavily into a semester he spent working in Kenya with the School for Field Studies. Based on that trip, he got a grant from the provost’s office to show his first exhibition in the Z. Smith Reynolds Library — a sign of things to come.

"I grew up in the suburbs, but I had one foot in the woods."

An Ogeechee Tupelo spreads its branches over a shallow sandbar in tannin-stained water flowing from the Okefenokee Swamp.

After graduating Ward took an internship with the photo department at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Later, through an internship at his hometown newspaper, an Amazon expedition with a mammal biologist and other work, he built a portfolio that convinced a Smithsonian team of his readiness to join them on a series of expeditions to Gabon in central West Africa. “The Gabon project is what really got me going professionally,” says Ward. “I came to understand the power of photography and visual communication for conservation.”

By late 2003, he had a Smithsonian cover shot, published his first book, “The Edge of Africa,” and placed photos from Gabon on exhibit at the United Nations in New York. He was ready for the next stage in his career and to head back to Florida.

Branding the Florida Wildlife Corridor

At home in Florida in 2006, Ward had something of a revelation. The state’s huge interior ranches had become a major focus. While photographing one in southwest Florida, Ward got to know some scientists. They were advocating protection of wildlife corridors for Florida animals like black bears and panthers that need long stretches to roam — stretches that can easily be blocked by development. Such lands play other critical roles. They can be the only places where species like the grasshopper sparrow — the rarest, most endangered bird in Florida and possibly the country — can survive. And they are essential in supporting a clean water supply for an ever-growing population.

Efforts to protect critical lands, and related research, have been underway for decades. But Ward saw an unfilled need to package such work in a form the public could more easily digest. He proposed branding these collective plans as the Florida Wildlife Corridor, and, eventually, a nonprofit he had founded to organize photographers to support land protection — the Legacy Institute for Nature + Culture — took on the name.

"The voter support for Amendment 1 gives me a lot of hope that the Florida Wildlife Corridor is still possible."

One of the researchers he met was Joseph Guthrie, at the time a graduate student. They discussed launching a first-of-its-kind expedition all the way from the bottom to the top of the state. “It was immediately apparent to me that he was an ‘up for anything’ type of person who was really adventurous, and just entertaining to be around,” says Guthrie. But he admits a bit of skepticism regarding whether Ward could pull off such a grand undertaking.

“We had no idea the scale of the task we were getting ourselves into,” says Ward. It was slow progress at first. Then, in 2008, Guthrie’s mentor and one of Ward’s inspirations, biologist David Maehr, died in a small-plane crash. “I remember the night of the accident Carlton calling me and saying, ‘We’ve got to make sure we tell this story; we’re going to do these expeditions so people know about this stuff,’ ” says Guthrie. And so they did.

On Day 26 of the Florida Wildlife Corridor Glades to Gulf Expedition, Ward dries out after a hike in St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge.

On Earth Day 2010, they unveiled a painting of the corridor with a sketchy green band running roughly up the middle of the state and a branch breaking off to the west across the Panhandle. All told there were some 15.8 million acres. About 60 percent of that is protected. The remaining 40 percent still needed protecting, or the corridor’s continuity would eventually be broken.

Finally, at dawn on Jan. 17, 2012, Ward, Guthrie — by this time a consulting biologist with the National Wildlife Refuge Association — filmmaker Elam Stoltzfus and conservationist Mallory Lykes Dimmitt, now executive director of Florida Wildlife Corridor, set out on the first Florida Wildlife Corridor Expedition. Ultimately by foot, bike, kayak and horse, and even a little swimming, they covered some 1,000 miles, capturing video, photos and stories that became a PBS documentary, a book and display material at Ward’s gallery, which he opened in Tampa in 2013. Along the way they met with ranchers, local Native American groups, politicians and reporters — just about anyone they thought needed to know about the wildlife corridor concept. “I’m always looking for that sliver of hope or the common ground,” Ward once told Watershed Radio.

A double-crested cormorant spreads its wings from the perch of a submerged sabal palm in the Rainbow River.

Funding land protection is challenging, but in November 2014, Florida residents approved a state constitutional amendment allocating new funds to purchase and manage conservation land. And they did it by a seemingly impossible margin given the current political climate: 75 percent. “The voter support for Amendment 1 really gives me a lot of hope that the Florida Wildlife Corridor is still possible,” says Ward, “and a lot of motivation to help share the story and give a face to these places we need to protect.”

"Most of the 20 million people in Florida don't have any idea of this Florida."

Manatee mother and calf come to the surface to breathe in Three Sisters Springs, Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge.

Determining how to spend that money has become a major political battle, one likely to continue for years. Some are wary of the state acquiring new lands it then has to manage. While that may be appropriate in some cases, of the 40 percent of the corridor still in need of protection, the vast majority is in private hands, in tree farms and large family or corporate ranches.

Such land can be protected through conservation easements. The state pays owners for their development rights, ensuring that the land remains agricultural while owners continue to handle all management. For families struggling to avoid selling off their land to developers as the state’s property values have climbed, the easements offer an influx of money, reduced taxes and a way to retain their lands, which offer relatively more natural wildlife and water protections compared to housing developments.

Two historically disparate groups see this as a positive outcome. “It always seemed like it was the cowboys or the tree huggers,” Ward’s cousin Doyle Carlton, a rancher, explains on the first Florida Wildlife Corridor video. “Then we finally got the barrier broke down and found out we have a common interest. We just need to create a common language to come up with a way to get to the same place, and I’ve seen a huge change in that on the positive side.”

Helping maintain the old Florida

Carlton Ward Jr. (’98) photographed this white egret near the Shark River Slough in Everglades National Park to bring attention to declining wading bird populations.

On Jan. 10 of this year, Ward and his team launched their second major trek, dubbed The Glades to Gulf Expedition, to highlight the western branch of the Florida Wildlife Corridor. U.S. Sen. Bill Nelson of Florida was there to see them off. “This is important for Florida’s traditions and legacy,” he said. “Carlton is bringing to life the real Florida and creating an environment in which the old Florida can still exist. Most of the 20 million people in Florida don’t have any idea of this Florida.”

But even those of us who think we know Florida can learn from what Ward is doing. Recently I joined him on a couple of flights over what’s called the Big Bend, where Florida bends to the west.

“This is about as vast and wild as it gets in the Eastern United States,” Ward said over the headphones, and I couldn’t see anything but green. Viewing the corridor from this angle helped me understand what a loss it will be if we break the corridor into pieces. What Ward is trying to show people, both literally and figuratively, is this grand bird’s-eye view. “I can’t yet say a piece of land has been protected because of this, but I hope that will be the case in the future,” says Ward.

"I came to understand the power of photography and visual communication for conservation."

To preserve ‘the real thing’

Before he died, Ward’s great-uncle, the one who expanded the family’s ranch holdings, set up something called Cracker Country at the Florida State Fair, a living history display that includes Gov. Doyle Carlton’s actual house. It’s a reminder of what life in Florida once was — which, like everywhere else, bears little resemblance to a world of interstates and air conditioners. But there are still expanses of land that look very much as they did then, and Ward is hoping generations to come can see and experience the real thing, the Real Florida, rather than a recreation of something long gone.

Between politics and development, he fears it’s not a done deal. But for now at least, in places like the Big Bend, you can fly and fly and see little else but green expanses cut by ribbons of blue. That includes a 570,000-acre parcel going up for sale — a sign that things could change dramatically and quickly if conservation efforts fail.

An American alligator glides through the reflection of spring-leaved cypress trees at Babcock Ranch Preserve in Charlotte County.

“I think one of the things that has kept me going as a photographer,” Ward says, “is the sense that I’ve been able to share a side of Florida with people that they haven’t previously known or appreciated.”

Guthrie, his biologist friend, says that sounds about right. “This is where Carlton really plays in,” he says. “I’m not sure too many people will understand the techno-jargon corridor language, but everyone can recognize beautiful imagery and start to realize that is what a lot of Florida actually is.”

"I am motivated to help foster a truer sense of place for the 18 million people who call this place home."

Carlton Ward Jr. set up his camera to capture time-lapse images as he explored Crawford Creek in the Chassahowitzka River delta, where Florida’s Nature Coast meets the Gulf of Mexico.

Mark Schrope (’93) graduated with a BS in biology. Based in Florida, he writes for such publications as Nature, Popular Science, The Washington Post and Sport Diver.