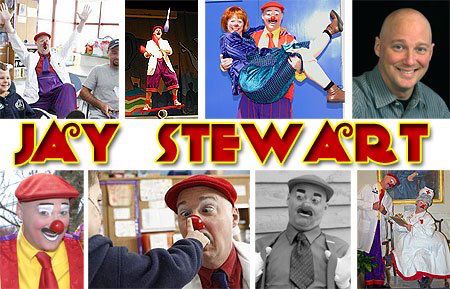

Jay Stewart (MA ’93) has traveled the country with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, taught at the circus’ Clown College and raised his kids on Clown Alley. He’s played Moe, Larry and Curly in a Three Stooges live show in Las Vegas, where he met a clown who became his wife. He’s been hit by pies in circuses from Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, to Japan and China.

Now he’s playing “Doc Skeeter,” a faux Southern doctor/inept handyman who dispenses laughs to acutely and chronically ill children. Laughter really can be the best medicine, said Stewart, a professional circus clown and variety artist who supervises the clown-therapy team at Boston Children’s Hospital and Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island. He’s there to pull some magic tricks out of his sleeve, juggle a few beanbags, run into doors and let the kids enjoy being kids and not sick kids.

Jay Stewart as Doc Skeeter (Photos courtesy of Boston Children's Hospital and Dr. George Taylor, Boston Children's Hospital)

“For those five minutes that we’re in the room, we want to help those kids and their families laugh together and be reminded that there’s still sunshine and laughter and hope in the world — and idiots who are willing to walk into walls to get you to laugh,” Stewart said. “Out of laughter comes hope, and from hope, the possibility of healing.”

Stewart, who lives in Harwich, Massachusetts, makes his hospital rounds several days a week. He looks like a normal 52-year-old until he paints a black mustache on his face and puts on a plaid red shirt, blue-jean bib overalls, a red nose and a red jug-head crown covering his bald head.

“Doc Skeeter” is neatly stitched on his white lab coat, his only nod to hospital decorum. Patches advertise his other lines of work: bus driver, lumber-yard worker, tire retread specialist, service tech. “I can’t be a doctor all the time, I have to make some money,” he explains. “I offer to service people’s tech all the time, but no one seems to take me up on it.”

The “doctors of delight,” as Boston Children’s Hospital describes Stewart and his sidekicks, use “the healing power of humor” to bring some lighthearted fun into the hospital. The clowns — including Dr. Gonzo and Dr. Mal Adjusted — are all professional clowns and variety artists who completed specialized training to work in a hospital. That means no pies in the face or buckets of water, and always asking a child for permission to enter his or her room.

“We don’t kick the door down and run in honking horns,” Stewart said. He might bang face-first into a door when he’s walking into a hospital room or “accidentally” bonk his partner clown on the head to get the show started. It can be a tough audience of sick children and scared parents. He’s liable to do some tap dancing or juggling or a goofy gag, whatever it takes to elicit a smile.

Children light up when Stewart enters the room, said Beth Donegan Driscoll, director of the child-life department at Boston Children’s Hospital. The clown-care program is supported by the nonprofit Foundation for Laughter, which partners with hospitals and schools nationwide. “Jay has such a strong passion for the work he does (bringing) moments of joy, laughter and excitement to patients and families during difficult times,” she said. “The hospital world disappears and is replaced with a world of fun and smiles.”

Stewart wasn’t one of those kids who dreamed of running away and joining the circus. He never even went to the circus when he was growing up in and around Atlanta. He had a much more serious career in mind when he enrolled at West Georgia College in Carrollton to study journalism. He changed his major to theatre after taking a theatre appreciation course. One of his professors suggested that he pursue a master’s degree at Wake Forest and study with Professor of Theatre Don Wolfe.

Stewart and a buddy from West Georgia, Sam Peabody (MA ’90), both enrolled at Wake Forest. Wolfe remembers Stewart as a hard-working student with a good sense of humor, but he didn’t see a future clown in the making. Stewart fancied himself as the next Laurence Olivier or Hamlet even though his roles leaned more toward comic relief than leading man. When he appeared as a comic pirate in a University Theatre production of “The Pirates of Penzance,” director and Professor Jim Dodding wryly observed: “You fall down well,” and suggested that Stewart try his hand at physical comedy.

"I have learned that kids in the hospital are just that — kids who happen to be in the hospital. I thought I needed to walk on eggshells and treat the patients with delicacy. I quickly figured it out; they are just kids and they appreciate getting a little rowdy sometimes!"

That was about the same time that Ringling Bros. rolled the Greatest Show on Earth into Greensboro. Stewart, Peabody and some other students, along with Dodding, made the short drive to see the show. It was the first time Stewart had ever been to a circus. The clowns mesmerized him; it wasn’t guys in whiteface blowing up balloon animals. Instead he saw in the clowns’ acts everything that he was learning at Wake Forest — physical comedy, character and story development, and how to connect with an audience.

Within weeks, Stewart had auditioned for and was accepted into Ringling Bros. Clown College in Venice, Florida. Even though that meant leaving school without finishing his graduate work, Dodding, Wolfe and Professor Harold Tedford (P ’83, ’85, ’90) were his biggest supporters, he said. “They embraced my idea to take my theatrical training and funnel it into a direction that I could relate to. I was never going to be Hamlet, but I could play the fool with the best of them.”

Jay Stewart, his wife, Kristin, and children Karen and Nick once had their own family show in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina.

After 10 weeks of learning slapstick techniques, acrobatics and makeup techniques at Clown College, he was hired by Ringling Bros. for its traveling show. He rode the circus train across the country for two years, performing 500 shows a year, until deciding to return to Wake Forest to finish his graduate thesis on, what else?, circus clowning. “Between Wake Forest and Ringling, I got everything that is important to me,” he said. “I discovered who I was at Wake, and Ringling gave me the opportunity to pursue that.”

With his graduate degree in hand, he rejoined Ringling Bros. and taught at the Clown College for four summers. He also played all Three Stooges, at different times, in Las Vegas. (“I was a bit schizophrenic. I was playing Moe one day and Curly the next. I couldn’t remember who I was supposed to hit.”) He had short gigs with circuses in Japan and China, before joining Ringling Bros. once again on the road as Clown Boss — writing and directing the clown routines and keeping the clowns in line — for four years, with his wife and children in tow.

He’s saddened that Ringling Bros. is shutting down this summer, but he’s optimistic that the circus, in some form, will survive. “There is too much history and too much tradition for it to go away forever. There’s an immediacy and authenticity to live circus performance that your television or computer can’t replace.”

Stewart, his wife, Kristin, and children Karen and Nick had their own family show in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, for several years before they settled down in Kristin’s hometown of Harwich, Massachusetts. His work on the clown-care team has been the most rewarding of his career, he said.

When parents follow him out of their child’s room and say “ ‘That’s the first time my kid has laughed in weeks,’ you can’t help but choke up. The clowns are a small part of a family’s experience at what must be the lowest time in their life. It’s an honor to be asked to try to make that experience just a bit easier.”