NEW YORK, N.Y. — From the company he built, from his offices on the 29th floor in midtown Manhattan, Mike Farrell on any day can survey the city for reminders of his father. Skyscrapers bear his father’s imprint. So do subways. Across the river, so does a primary school in Old Bridge, N.J. And soon, nearly 600 miles away, Wake Forest will, too.

MIKE AND HIS WIFE, MARY FLYNN FARRELL, of Summit, N.J., parents of alumnus Michael Edward Farrell (’10), made Wake Forest history in October with their pledge to give $10 million toward the construction of a building for the Schools of Business. To be paid over three years, the gift is the largest cash commitment by a living individual in the University’s history and the largest donation to date to the business schools.

With construction set to begin this spring, the three-story, 110,000-square-foot center estimated to cost nearly $50 million will be named Farrell Hall in honor of Mike’s late father, Michael John Farrell, and underscores the Farrells’ support of leadership excellence in business and education. “I can hear him laughing to say that’s his name up there,” Mary says from her yellow wingback chair in her husband’s offices on Avenue of the Americas in Midtown. Dressed in his charcoal-gray cardigan buttoned up Mister Rogers-style, Mike sits in a matching chair in an office that features, he points out, Deacon colors. Mike and Mary smile at the thought of their gift, this tribute to a blue-collar Irishman so intimidated by higher education that he refused to set foot on the campus of Trinity College Dublin, around the corner from where he grew up.

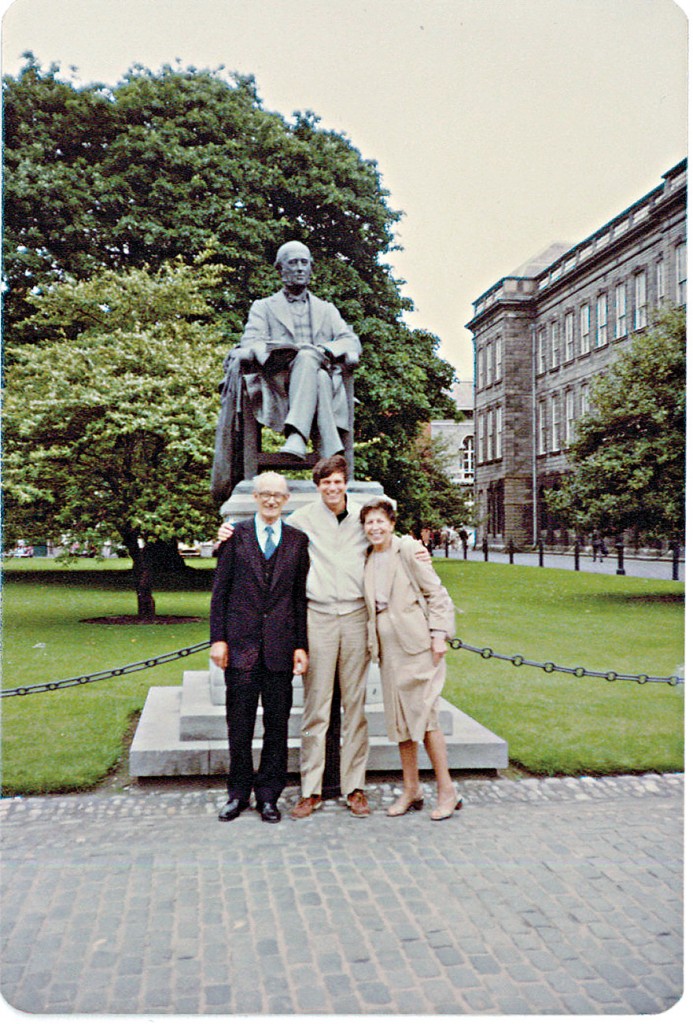

“He felt like he didn’t deserve to be around college kids,” Mike has said. “He literally had to be dragged onto the campus grounds.” Mike and Mary took him to Trinity College in 1983 when they met Mike’s parents in Dublin on a stop during their honeymoon. His father wore a suit for the occasion. The photograph from that day remains one of Mike’s favorites.

“This man had an unbelievably tough life — Depression, war, immigration,” Mike says. He was not one to speak of personal hardships, and his son says for a long time he and his father didn’t get along. They made peace before the end. His father died in 1986 at age 66. Naming the building, he says, “is an honor to him.”

IN DAYS GONE BY, ACROSS THE OCEAN, Farrell ancestors lived large. During medieval times, they were the O’Farrells, the reigning clan of Longford. They ruled from Annaly Castle in Ireland, which exists now only in family lore, and, in midtown Manhattan, in the crest dominating the logo and the handcrafted reception desk of Annaly Capital Management, Inc., the largest residential mortgage real estate investment trust listed on the New York Stock Exchange. It is the company, one of several, that Chairman, Chief Executive and President Mike Farrell has built with great success in the last two decades. His companies manage over $90 billion of primarily agency and private-label mortgage-backed securities.

The Farrell patriarch would follow the hardscrabble path of European emigrants to 1940s Manhattan, a journey worlds apart from his son’s. But first, as a young soldier, he saw combat. A member of the Irish Guards, he was part of a failed, devastating campaign by the Allies in September 1944 known as Operation Market Garden. Thousands of British troops died, among them an Irish tank driver named Austin Michael Murphy. “I found out recently that my dad was the only one to walk away from the tank,” Mike says. His namesake is that tank driver, his father’s friend, buried in Arnhem Oosterbeek War Cemetery in the Netherlands, his gravestone visible when Mike did a Google search combing for signs about whether to make the Wake Forest donation and lend his father’s name to the cause.

AFTER THE WAR, THE ELDER FARRELL and his wife, Vera, left Europe for America, and it was in New York that Mike’s dad found a place in the real estate boom. Waterproofing and caulking skyscrapers: those were his jobs. He clocked in workdays atop scaffolding hanging from unimaginable heights until he could bear it no more. Vertigo in his early 50s sent him to toil for the betterment of the city’s depths, no longer its heights. He became a painter of subway cars for the New York City Transit Authority. Later, he would land his prized job: janitor at an elementary school in Old Bridge, N.J. He cleaned the kindergarten and first-grade classrooms, where students would leave him notes. “He glowed when he would bring those notes home,” Mike says.

Mike was born in Brooklyn in 1951, Mary in Long Island in 1957. Neither finished college. Calling his “an interesting journey,” Mike graduated high school at 16, set on becoming a commercial artist. He ended up, as he says, a tall, skinny kid playing basketball in New Mexico in a strange land of cowboys and guns, crop reports and Yankees fans as scarce as water in the desert. He ran out of money and dropped out, heading back East to become a rock star. That plan went bust. His ascension in the financial world began when he proved himself fit on an IQ test for E.F. Hutton & Co.’s management training program. He mastered Wall Street, learning all aspects of the business. “I understand how the stuff is made and where it goes. I liken myself to a mechanic,” he says, a skill set he credits with saving him many times during his career, “including the latest mess.”

Mary grew up in Long Island, the daughter of a father who worked at a Ford dealership and a mother who worked at a community bank. “They said, ‘You can apply to one college. If you get in, great. Figure out how you’re going to pay for it.’” Mary was ready to begin her senior year at St. John’s University in Queens when she thought twice about adding to her mountain of student debt. She dropped out. “That was my education,” she says. “I do wholeheartedly believe this: We went to the school of hard knocks.”

THEY MET AT A WALL Street firm — Mary was a sales assistant for a time — and married. The Farrells’ financial success created a markedly different life for their three children. Their eldest, Caitlin, graduated from College of the Holy Cross in 2008. Their son majored in finance and economics at Wake Forest. Their youngest, Taylor, is a high school senior. Caitlin works for her father in his Boston office, Michael Edward in New York, “a taxpayer now,” his father notes by way of introduction.

The Farrells praise their son’s experience at Wake Forest as intellectually rigorous and socially vibrant. “We believe in the school,” Mary says. “It definitely comes under what our philosophy is, where things should be going.” The Farrells speak of the values-based education they saw at the University, with Mary’s definition of values as “civility, responsibility and accountability.” A founding member of the Schools of Business Board of Visitors, Mike was struck by Bill Leonard’s speech marking his retirement as dean of the divinity school; President Nathan Hatch’s quest to educate “the whole person” and his willingness to discuss faith; and Provost and Professor Emeritus Edwin G. Wilson’s (’43) speech about Wake Forest’s being a unique institution where friendliness and honor remain touchstones.

“We went there looking for academics,” Mike says, “and we found a place where there was a discussion about community service, faith, academics.”

WHILE THEY ACKNOWLEDGE QUIETLY providing donations for educational causes in the past, particularly Catholic schools in their area, the pledge to Wake Forest is their largest and most public gift. Farrell Hall, expected to open in the summer of 2013, will use state-of-the-art technology and groundbreaking design to foster heightened faculty-student engagement, which the Farrells hope will encourage Socratic inquiry, mentoring and conversations among graduate and undergraduate students that might spark innovation.

Despite the sluggish economy, Mike sees the push for the new building as timely: “The Empire State Building, the Rockefeller Center –— these things were built during the Depression when people didn’t think they were achievable. When people are confused and scared and concerned about direction, you need to send a strong message that we can’t stop thinking about the future … We need to make sure we have the right leaders in place, and places like Wake create those leaders.” They want their gift to pull others to the cause of supporting a University that, as Mike puts it, “has not gone corporate.”

If his father were alive to see the building taking shape, Mike has no doubt he would be assessing it differently than would his son the businessman. He would cast a construction worker’s eye on the Georgian brick and say, “Let’s make sure we get this lined up right.”

Mary says, “He would get a real kick out of this. He really would.”