An example of life for all. When I will become father, I will tell your history to my sons.

-Ivan Merli (from Italy)

E bellisimo…quel coac e un angelo

– Da Rosario

This is why I love Wake Forest. Pro Humanitate

– Amelia Knight

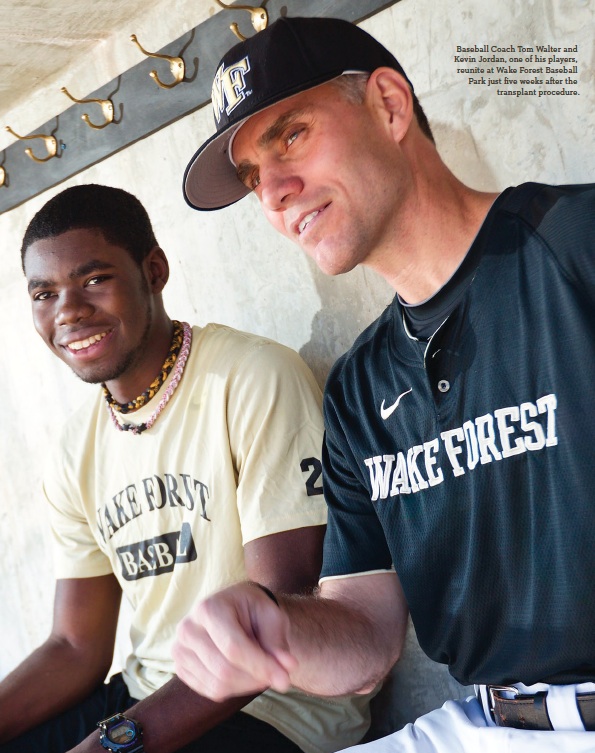

Pro Humanitate. As people struggled on the Wake Forest website and various sports blogs to find the words, in any language, that summed up the humbling exchange between Deacon baseball Coach Tom Walter and his centerfielder, Kevin Jordan, many found sanctuary in the University’s motto.

It’s not a bad place to land when you’re wrestling with a story that will, I believe, forever change the way a great many people think of Wake Forest. For a little perspective, however, Pro Humanitate is not the Latin phrase that inspired or unnerved the generation that arrived on campus in the mid-’70s.

No, that would be, In loco parentis, the admonition that the University felt compelled to serve as the chaperone, alcohol monitor and curfew enforcer we were so desperate to avoid.

In loco parentis. In place of a parent. That pledge was so ominous then … and sounds so different now for those of us who’ve brought children into the world and released them into the wild. Keith Jordan, Kevin’s father, speaks for many of us: “Sending him seven hours away from home, we were heartsick. We’d never been separated that long. It was pins and needles. But you have to have that faith, that understanding that everything happens for a reason.”

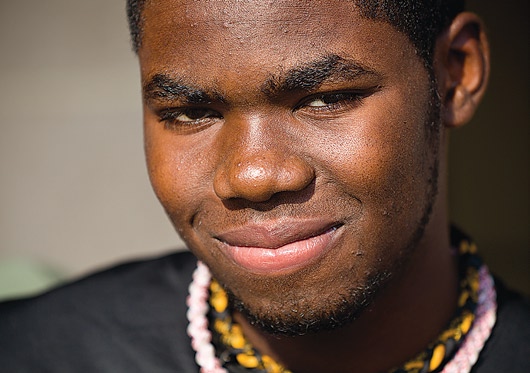

Kevin Jordan had far more of the unreasonable on his plate last year than the average freshman. In the late spring of 2010, doctors at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta finally discovered why the Columbus, Ga., baseball star was losing strength and weight: ANCA vasculitis, a nasty autoimmune disease that had crippled his kidney’s ability to function.

Between those daunting first-semester classes, Kevin was spending 11 hours a day handcuffed to a dialysis machine. He’d lost 40 of his 198 pounds, and most of his power and speed, when he and his parents sat down in August with Coach Tom Walter at the Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center to hear Dr. Barry Freedman describe Kevin’s health issues.

Keith Jordan remembers worrying the Deacons would pull his son’s scholarship: “Most schools probably would have. Here’s a kid coming to school and he can’t help my team.”

What does Tom Walter remember? “Looking at our trainer (Jeff Strahm) with my mouth hanging open. I couldn’t believe what this young man had gone through.”

And he couldn’t stomach what Kevin would have to deal with unless he received a kidney transplant. “The wait time on the donor list is a minimum of three years,” Walter said. “Fifteen people die every day waiting for a kidney.”

At the end of Freedman’s candid update, Walter didn’t hesitate. “I wanted to be tested,” he told the Jordan family, “because I think I might be a match.”

“I think we have it covered,” Keith Jordan said.

He didn’t know how wrong, nor how right, he was.

Walter — in his second year coaching the Deacons — grew up in Johnstown, Pa., and survived one of the great floods that deluges the town every 50 years or so. And he was coaching at the University of New Orleans, on the rim of Lake Pontchartrain, when the floodwaters of Hurricane Katrina swamped the city in 2005.

His Privateers spent the next six months practicing and playing at New Mexico State and South Alabama before finally returning to New Orleans in early February 2006. The baseball field remained the eye of their storm. “We called it ‘The Alamo,’” Walter said. “Everything around us was devastated, but the flag was always flying in centerfield. It was our sanctuary, no matter how bad things were around us.”

Walter always believed he was meant to be in New Orleans when the hurricane hit. He felt a similar sense of intervention and the divine when he realized Kevin could not find similar sanctuary at Wake Forest, even as the freshman was slowly drained of energy and hope.

When Kevin’s mother, Charlene, and his brother did not qualify as a donor match, the Jordans turned to his coach. After the tests were complete and the transplant was scheduled, Walter called his parents, who now live in Virginia.

“Are you okay with this?” his mother, Anne, remembers him asking.

That she’d raised a son who was willing to make that kind of sacrifice? Yes. She was okay with that.

“All I could think of was Charlene, Kevin’s mother. All I could do was put myself in her place,” Anne Walter said, “and think how I would feel if it were the other way around.”

There were two surgeries on that February morning at Emory University Hospital. Dr. Ken Newell operated on the 42-year-old donor and Dr. Alan Kirk on the 19-year-old recipient, and it’s safe to say the immeasurable gap between giving and receiving vanished in the private waiting room reserved for their families.

Tom Walter’s parents were there with Keith and Charlene Jordan. They sat together through that anxious morning, and there was nothing, Anne Walter said, quite like the moment when Kirk arrived to say the new kidney was in and — e bellisimo! — working like a charm.

“The look on their faces,” Anne said, “particularly Charlene. I was holding her hand. I get teary-eyed thinking about it. She was unbelievably happy.”

“You live in faith. You have to understand that piece of it,” Keith Jordan says, two months later. He is still getting calls from people who want to talk about his son and the kidney they have decided to donate.

Tom Walter still struggles a bit to catch his breath when he climbs a flight of stairs, but he’s back at the local Alamo with the Deacon baseball team, hitting fungos and tending the flock.

And Kevin Jordan — who is back up to 185 pounds and will be back on campus for summer school in July — is working out again at Momentum Physical Therapy and Northside High School in Columbus.

“It’s pretty tough to do a sit-up,” he admits. “The area where the surgery was is real sore. But swing a bat? I don’t feel it. Run at full speed? I don’t feel it.”

He and the original owner of his kidney talk every week.

Not long after he emerged from surgery, Kevin Jordan said this: “I’m just really thankful. I don’t think I have the words for it in my vocabulary.”

Few of us do. That’s why we turn to the Latin.

In loco parentis.

The belief, the hope, the promise that another parent — or community of parents — will care for your son or daughter with the same devotion that you do.

Some of us are lucky. We happened upon Wake Forest, often by chance, and when we’re asked why we love the place, we remember Sunday mornings on the Quad, Saturday nights at the stadium and Wednesday afternoons with the romantic poets.

But everyone else? This is the story they will remember. When they hear the words “Wake Forest,” they will celebrate the kidney that passed from Tom Walter to Kevin Jordan, a gift as big as life.

And when they become fathers, this is the history they will tell their sons.

Steve Duin (’76, MA ’79) is metro columnist for The (Portland) Oregonian. He is the author or co-author of six books, the latest “Oil and Water,” a graphic novel illustrated by New Yorker cartoonist Shannon Wheeler and to be published this fall by Fantagraphics.