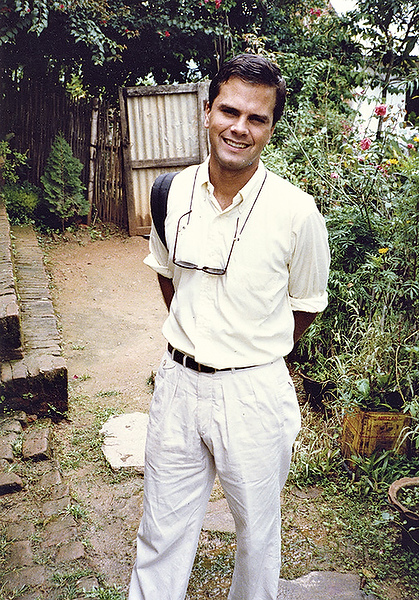

Soon after arriving in a remote area of the Dominican Republic in 1990, Dave Meyercord (’89) sensed the gravitas of John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s words that life in the Peace Corps “would not be easy but it would be rich and satisfying.”

His first task as a volunteer was to build his own one-room house from the wood of a fallen avocado tree, assisted by machete-wielding villagers. Surrounded by the rugged peaks and fertile valleys of Los Bolos, he dug latrines, built aqueducts and grew attached to a mule named Abigail who provided his daily transportation up and down a coffee orchard-covered mountainside.

As a successful public relations executive in Chicago, Jane O’Sullivan McDonald (’89) walked away from a comfortable middle-class life in 2009 to join the Peace Corps. She wanted hands-on humanitarian experience to prepare for a midcareer change. In Togo, Africa, she drafted constitutional documents, assisted with polio vaccines and ironed her clothes regularly — not to remedy wrinkles but to eradicate bugs that attached themselves during the laundering process.

Arthur Orr (’86) followed in the footsteps of Wake Forest’s more than 200 alumni Peace Corps volunteers, spending 1989-91 in Nepal after completing his law degree. He taught children and trained teachers in a one-room, dirt-floor structure. His village of Khanbari was more than two days from the nearest road; his home, a mudwall structure with a tin roof. He ate rice and lentils twice a day, every day, except when the villagers served up an occasional chicken.

Like many Wake Foresters whose personal journeys embrace the quest to live an examined and purposeful life, Meyercord, McDonald and Orr had a strong desire to serve those in need and experience international culture. They applied to and joined the Peace Corps, America’s iconic humanitarian organization observing its 50th anniversary this year. Once described affectionately by writer Paul Theroux as “a sort of Howard Johnson’s on the main drag into maturity,” the Corps’ roots and mission go back to 1960, when then Sen. John Kennedy challenged students at the University of Michigan to serve their country in the cause of peace by living and working in developing countries.

From Kennedy’s inspiration to unite American ideals with a pragmatic approach to bettering the lives of people worldwide grew an agency of the federal government — with Kennedy’s brother-in-law, R. Sargent Shriver Jr., as founding director. It has three goals: helping the people of interested countries in meeting their need for trained men and women; promoting a better understanding of Americans on the part of peoples served; and promoting a better understanding of other peoples on the part of Americans. Assignments are for 27 months, three spent training in the host country and 24 in actual service.

“The Peace Corps is more than a program; it’s an idea,” says Mark Kennedy Shriver, son of the late Sargent Shriver and Eunice Kennedy Shriver, sister of JFK and founder of Special Olympics. Shriver, senior vice president for U.S. programs with Save the Children, will speak at a Voices of Our Time event on Oct. 13 in Wait Chapel. Wake Forest, which has ranked among the top 25 small colleges and universities with more than 200 volunteers in 77 posts, will honor them on the occasion. Says Shriver, “Wake Forest’s mission to make our nation and our world a better place through service is remarkable evidence of that concept.”

An Obligation to Give Back

Now an Alabama state senator, chair of the Finance and Taxation General Fund Committee and president of the Wake Forest Alumni Council, Orr had never been out of the United States until his sophomore year when he went to Haiti for mission work. In Nepal he found teaching resources limited to a few textbooks, which teachers read to pupils, who learned by memorizing what the teachers said.

He realized there were many bright students — particularly young girls — who, because of cultural mores, would probably marry early and become mothers, never achieving their academic potential. His letters to family and friends generated enough support to establish the Khanbari scholarship in the ’90s. “Over 80 students have been able to attend college because of the scholarship,” says Orr, who recently returned from a sentimental visit to Khanbari with his wife and son. “The scholarship board has gone on to extend benefits to disabled children and children of lower castes.”

While she was helping local Togo associations manage themselves more efficiently, McDonald started a girls’ club and served as liaison between Rotary Clubs in the United States and Togo to provide desks to elementary schools and playground equipment/supplies to kindergarteners. Many projects were not without their challenges as the area’s ethnic groups did not always get along, says McDonald, who returned to Chicago in July and has been making presentations to Rotary Clubs that helped fund her Peace Corps projects.

Night after night as she lay under a mosquito net watching spiders and geckos climb the walls, McDonald was sustained by the lesson of giving of one’s self unconditionally, modeled by many Wake Forest mentors — Ed Wilson (’43), Ed Christman (’50, JD ’53), the late David Hadley (’60) and the late Bill Starling (’57), to name a few. She recalled a conversation with Professor of Art Peggy Smith in which Smith discussed how, at several points in her life, she was challenged to “reinvent” herself. “The conversation has remained with me as a lesson in resiliency, patience with oneself, and never being afraid to take significant risks even if the risks make you uncomfortable,” McDonald says.

Night after night as she lay under a mosquito net watching spiders and geckos climb the walls, McDonald was sustained by the lesson of giving of one’s self unconditionally, modeled by many Wake Forest mentors — Ed Wilson (’43), Ed Christman (’50, JD ’53), the late David Hadley (’60) and the late Bill Starling (’57), to name a few. She recalled a conversation with Professor of Art Peggy Smith in which Smith discussed how, at several points in her life, she was challenged to “reinvent” herself. “The conversation has remained with me as a lesson in resiliency, patience with oneself, and never being afraid to take significant risks even if the risks make you uncomfortable,” McDonald says.

After arriving in Los Bolos, Meyercord’s job was to address their greatest need: sanitary water. “If you could get to the source it was clean but getting to it was a problem, and it always fell to the women,” says Meyercord, who is senior vice president of Elwood Staffing in Columbus, Ind. “One woman calculated the number of hours she spent every day going to get water; she determined she spent 32 days out of every year doing nothing but getting water.”

He and other volunteers designed and built an aqueduct system that brought water to the village. They built two schools and cajoled the country’s Minister of Education into furnishing desks and hiring a teacher. Another sign of progress came when a navigable road was cut where Abigail had carried him up and down the mountain. With the road in place, he got a motorcycle and Abigail went on to serve another volunteer. Theirs was an emotional farewell.

‘Even the Business School Qualified’

While many alumni were influenced to join the Peace Corps by Wake Forest’s mission of Pro Humanitate, in Charles “Chic” Dambach’s case it worked the other way around; he enrolled in the business school a decade after graduating from Oklahoma State University and serving in the Peace Corps. “The Peace Corps influenced me to want to do graduate studies at a school that embraced humanitarian value, and Wake qualified; even the business school qualified!”

Being a student of the ’60s, Dambach (MBA ’77) of Washington, D.C., says joining the Peace Corps seemed to him the natural thing to do. “I had been deeply moved by the Kennedy challenge to “ask not what my country could do for me, but what I could do for my country and the world.” At Oklahoma State University, a football teammate pulled him aside his freshman year and urged him to consider the Peace Corps after graduation. James Ralph Scales, dean of the OSU School of Arts and Sciences who would eventually become the eleventh president of Wake Forest, was influential in Dambach’s decision.

Serving in Colombia from 1967-69, he was assigned to the “invasion” barrios of Cartagena on the Caribbean coast. There he experienced the darker side of what many knew as a beautiful port city; squatters lived in shanties made of scrap wood and metal with no running water, electricity or health care. He worked with local villagers to build a school and organize a fishing cooperative and vividly remembers listening to the first moon landing on a battery-powered radio.

Dambach, president and CEO of Alliance for Peacebuilding who wrote “Exhaust the Limits: The Life and Times of a Global Peacebuilder,” came back with a different definition of success and prosperity, taught him by the people of Cartagena. “Bigger cars and TV sets became irrelevant; deeper friendships and time to enjoy them became a priority,” he says. “I gained tremendous respect and appreciation for the people who are born with nothing of material worth but enormous human spirit and resilience.”

Other Peace Corps alumni, including Bobby Ray Gordon (JD ’86), credit Wake Forest’s emphasis on ethics and service with reinforcing their humanitarian values. “I strongly believe that those who were fortunate to be born in a developed country have a duty and obligation to give back to those who were not so fortunate,” says Gordon, who interviewed Vietnamese refugees in Hong Kong to determine if they were eligible for asylum. Now a humanitarian operations adviser for a Department of Defense organization in Honolulu, he adds, “I wanted to make a difference in the world and, for at least a few persons, I know that I did.”

Kelly Chauvin (’08) owes a debt of gratitude to two Guatemalan staff members who worked in Efird residence hall, Reina and Marciano Alvarado. They helped her practice Spanish and learn about their country, where she is in her third year as a volunteer specializing in ecotourism. “Every day I am rewarded by people who are friendly and want to talk with me about a new idea or a new recipe, or invite me to a soccer game,” says Chauvin, from Hillsborough, N.C. “It is a wonderful way of life and many aspects would be good to incorporate more in our lives in the U.S. I am grateful to Wake Forest for giving me the tools I needed to be successful here.”

A trip to Honduras as a Hope Scholar was a formative experience during Scott Richards’ years at Wake Forest. Assigned to the Bolivian village of Quechua, Richards (’01) worked with children on gender and self-esteem issues. He was known as “Big White” because of his ability to reach out and touch a basketball net. “I was the only foreigner and the only white guy,” says Richards, who works at a microfinance investment firm in New York City. “It was my first time feeling that I was an outsider; after the Peace Corps I had a desire to go somewhere and be completely anonymous.”

New Perspectives on Life’s Blessings

To this day Arthur Orr holds dear a painting that depicts a man with a mallet breaking up stone to be used as aggregate for mortar. It’s a practice he saw many Nepalese families do 14 hours a day just to make a meager living. “Unless you understand poverty it’s difficult to understand the greater world and how it operates,” he says.

Time spent in Africa made Jane O’Sullivan McDonald more appreciative of life’s blessings, helping her to better understand the difference between “want” and “need.” After living in a country sorely lacking in roads, sanitation systems and the means to provide a minimal level of public education, she has a healthier respect for the services and goods her tax dollars support.

Dave Meyercord returned from the Dominican Republic with his future wife and a profound appreciation for his homeland. “No matter how much you fancy yourself as a do-gooder, there’s a certain level of arrogance that can come with that: ‘I’m going to help these heathen natives’ — that was the old-school mentality,” he says. “One of the things you realize is that you learn as much, if not more, than you teach. You learn about yourself and your capabilities, and you learn a lot more about the U.S. by leaving it rather than being in it.”

Those who served speak of heartbreaking poverty and heartwarming smiles, annoying bugs and affectionate children, unimaginable despair and indescribable triumphs. With a new global perspective and humbling sense of self, they remember their Peace Corps experience not in terms of what they did for their country, but what their countries did for them.

Campus exhibit honors local Peace Corps volunteers

The Museum of Anthropology is observing the Peace Corps’ 50th anniversary with an exhibit that brings to life the service of Triad-area volunteers, many with Wake Forest connections.

The exhibit, open through Dec. 16, includes a documentary film as well as photos, clothing and objects brought home by returning volunteers. “We wanted to explore how the Peace Corps experience changed their view of their own world and their country’s culture,” said Steve Whittington, MOA director.

A reception for alumni who were in the Peace Corps is planned for Oct. 14 during Homecoming Weekend, from 4:45 to 6 p.m.

Senior anthropology/sociology major Abbey Keener and documentary filmmaker Roman Safiullin (MFA ’11) produced the exhibit. Keener earned academic credit for the internship project, that included interviewing Peace Corps veterans and organizing items for display. Safiullin, who graduated from the Documentary Film Program in May and co-directed “Bound by Haiti,” videotaped the interviews and edited them into a short film.