The Bedouins spoke of them as “The Five.” They had come to the foot of Mount Sinai in Egypt, to the remote St. Catherine’s Monastery, and they did stick out a bit. They had crossed the desert with a strange load of equipment described with some creativity to customs officials, they were American, and one of them stood 6’8″ tall. The team was there on a technological aid mission of sorts, aiming to digitize the pages of ancient manuscripts for preservation, and to reveal secret texts hidden for centuries. They were hoping that the men outside the monastery, the ones from the Egyptian government speaking Arabic into walkie-talkies, weren’t going to interfere.

This desert sojourn was the latest in a string of adventures in history that began in 1999 when Michael Toth (’79), the tall one, offered his services to a museum group embarking on an unprecedented study. They were about to analyze one of the oldest known copies of works by famed scientist and mathematician Archimedes, who lived in the third century B.C.

Taking part in such a project wasn’t an obvious extracurricular path for Toth, but it wasn’t a bad fit either. Arriving at Wake Forest in 1975, Toth (pronounced like “oath”) began as a biology student, but he shifted to history after realizing he didn’t want to spend the money or time it would take to go on to graduate school and become a scientist. “I wanted to get out in the world,” he says. And that he did, quite literally.

He went to work for the Foreign Broadcast Information Service, a non-secret branch of U.S. intelligence that once monitored publicly available news in regions around the globe. Youngsters will have to imagine a world where you couldn’t get nearly every piece of news available on the planet from a device that fit in your pocket. You had to work for it, and that’s what Toth did.

The service needed well-rounded people who could follow a wide range of topics, and Toth’s liberal arts studies at Wake Forest helped convince them he could do it. He would end up managing teams of translators and technicians in Central America, Southeast Asia and Southern Africa. “It was the best job in the world. We listened to the radio, watched television and read newspapers,” he says. “We just had to do it all at the same time.”

Eventually, he shifted to working on satellites for NASA and the Department of Defense, even supporting a classified space shuttle mission in 1989, which meant a welcome chance to spend time in Florida, where he grew up. By 1999 he was the policy director for the National Reconnaissance Office, a secretive surveillance branch of the U.S. government.

That year, 1999, also marked the beginning of the historic effort to study a remarkable, if decidedly unattractive and moldy, handwritten book now known as the Archimedes Palimpsest, or “Archie.” An anonymous donor known only as Mr. B had just picked it up at auction for $2 million, and he intended to pay for an advanced analysis of the manuscript’s pages.

When Toth, who lives in Virginia, read about the project in The Washington Post, he contacted Will Noel, the curator overseeing the project at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. Toth suggested that he might be able to help with Archie’s advanced imaging thanks to his experiences handling satellite imagery for the intelligence community and his connections among scientists and technicians who conduct such work. Noel and Mr. B liked the idea so much that Toth became the project manager.

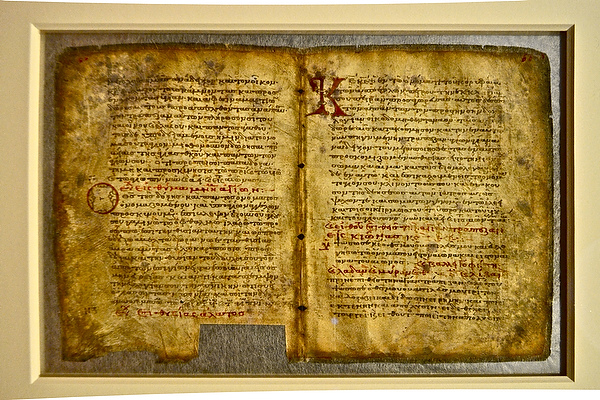

Palimpsest Leaf in natural light with the sole extant copy of the Archimedes “Method of Mechanical Theorems” in the undertext

In its original form, produced centuries after Archimedes’ death, Archie was a 10th century A.D., handwritten copy of seven of Archimedes’ most important works in the original Greek, including the only known copies of “The Method, On Floating Bodies” and “Stomachion.” Though probably best known for his law for calculating buoyancy, Archimedes’ works were foundational in mathematics, physics and engineering.

In 1229 A.D., Archie ran into some troubles. Animal hides were in short supply, and a priest needed a new prayer book. This seemed more important at the time than the Archimedes text, which he scraped away to scribe his new book. Pages thus recycled are known collectively as a palimpsest.

The entire history isn’t clear, but in 1899 Archie was in Jerusalem, in the possession of the Greek Orthodox Church. In 1906, a scholar named Ludwig Heiberg discovered the Archimedes writings hidden below the prayer text. Details are even fuzzier after that. There may have been some involuntary exchanges. But despite a legal challenge by the church, which U.S. courts ruled baseless, the manuscript sold to Mr. B at Christie’s auction house at the end of 1998.

Once Mr. B had it, he dropped Archie off without fanfare at the Walters Museum in an off-limits work area that also houses a 17th century Shakespeare collection, a Napoleon diary and letters from Catherine the Great, among case after case of other treasures.

With Mr. B graciously picking up the tab, Noel and Toth assembled a team that included experts to handle long-term manuscript preservation, scientists to do the imaging, and language and Archimedes scholars that could make sense of what the work revealed. “It was a very complicated problem because you’re trying to integrate all these different worlds,” Toth says.

One of Toth’s jobs was to help line up the academic groups, several of which were applying for the privilege, to image the book’s pages. At the time, many experts believed that past studies had already revealed everything that could be gleaned from the pages. But Archie had never been subjected to the most advanced technologies. A multi-institution group of U.S. scientists would ultimately use something called multispectral imaging to make a series of revelations.

This technology involves taking high-resolution photos using different colored lights, including some not visible to human eyes. The color of light is determined by the distance between the peaks in the waves of energy that emanate from a light source. Those waves interact differently with different types of materials, such as inks. A crime scene investigator using fluorescent lights to detect otherwise unseen blood represents an example of this principle because light in fluorescent wavelengths resonates with blood molecules, causing them to reemit light visible to the human eye.

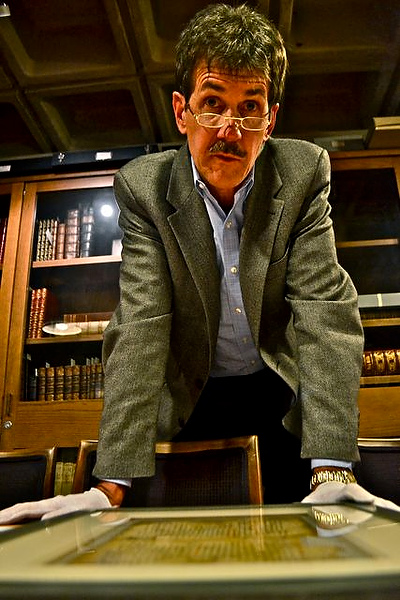

A cultural sleuth, Michael Toth (’79) travels the world to examine rare documents with sophisticated digital imaging.

But multispectral imaging is decidedly more complex than a spot-check for blood. The researchers used computers to process numerous images of a given Archie page, each taken under a specific color. Then they digitally manipulated slight differences between these images to enhance the faint traces of underlying ink that recorded Archimedes’ works, as well as those of other authors, and to suppress the prayer book text. It took years, but the work was remarkably successful.

Sadly, there were four pages that a forger, probably sometime around 1940, painted over to make the book more attractive to collectors. To “see” through this gold paint, the team turned to a different group of scientists who used a powerful X-ray beam at Stanford University’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, which was able to produce images of iron used in the ink of the underlying text.

In 2008, just hours before a self-imposed one-decade deadline, the team publicly released images of all the pages on the Web. And in October of this year, the Walters Museum will begin a long-awaited exhibition of select leafs.

“With all the projects I’ve worked on the goal is to always ensure the data become available for the public good,” says Toth. In the process, they developed standards for data storage and preservation that are becoming widely used for other historic projects.

Even before releasing the images, team scholars had found evidence in Archie’s pages that Archimedes understood and worked with a more advanced concept of infinity than anyone had realized, and that he had described the foundations for the science of probability. All of this further supports the notion that Archimedes was one of the most influential thinkers in history.

LIVINGSTONE, LINCOLN & JEFFERSON

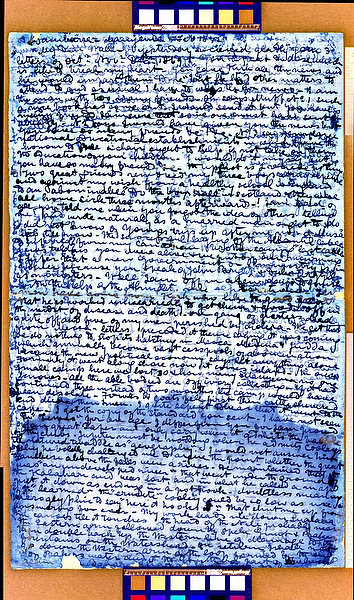

By the time the Palimpsest project was complete, Toth had retired from his government job and shifted to historical work nearly full time. Among other projects, including imaging a diary of famed Scottish medical missionary and African explorer David Livingstone written on old newspapers, he has worked extensively with the U.S. Library of Congress. There, curators are studying treasured historical documents using techniques similar to those applied to Archie. In a lab space next to one of the library’s several vaults, Toth helped them set up a spectral system. There, in a room painted black, when the regular lights go out, a precisely tuned cycle of colors illuminates a document as a high-resolution camera captures the images.

Computer-processed spectral images of one of famed explorer Dr. David Livingstone’s 1870-71 diary pages from his last Africa expedition overwritten on a piece of newspaper.

If this sounds like something out of the movie “National Treasure,” where Nicolas Cage’s intrepid character finds hidden secrets on historic documents, that’s because it is. The movie’s producers requested a photograph of the group’s spectral setup to recreate for the film.

There are about 145 million items in the Library’s collection, so curators allow that they can’t quite give each one the attention they might like. There’s no telling whether secret codes may be lurking somewhere, but the work has already revealed treasures of a sort.

While reviewing an enhanced image of the original draft of the Declaration of Independence, Library preservation scientist Fenella France noticed something odd. Some letters seemed to be smudged out and replaced with the word “citizens.” The erased word, spectral imaging revealed, was “subjects.” As Thomas Jefferson wrote, he must have remembered the ramifications of the Declaration. Toth says, “You can see the mind going there, ‘We’re not subjects anymore; we’re citizens.’ ”

It was Toth himself who made the next attention-grabbing discovery. Working with a copy of the Gettysburg Address that Lincoln may have used when he delivered the famous speech, Toth spotted another smudge. The document was tri-folded, perhaps to fit in Lincoln’s coat pocket, and the smudge is a fingerprint right about where Lincoln’s thumb might have been. France is working with the Army’s Criminal Investigation Lab to see if they can find a Lincoln fingerprint somewhere for comparison.

Of several other documents they’ve worked with, Toth especially enjoyed the chance to study a handwritten copy of one of Beethoven’s concertos. It revealed no hidden text or ink markings, but he says the score’s big, bold, black curves seemed to match the music. “Sometimes you’ve got to pinch yourself and go, ‘Beethoven himself wrote this,’ or ‘This was Abraham Lincoln writing,’ ” says Toth.

Toth using spectral imaging at the Library of Congress to examine the Gettysburg Address in search of Lincoln’s thumbprint.

WHAT FATE AWAITS MODERN INFORMATION?

One thought-provoking theme that runs through all the projects is the nature of information and how we handle it. “Where is Jefferson’s smudge in the 1s and 0s? Where is that?” Toth wonders of today’s computerized information.

Perhaps an even more important question is where all our 1s and 0s will be 100 years from now, or 1,000. Writing by hand on animal hides may be archaic. But the fact remains, at least some documents from 1,000 or more years back are still around and readable. Yet as Toth points out, how many of us can even pull information from a 1985 floppy disk? For his work, he seeks not the most cutting edge electronic storage options but the most basic and well-established ones most likely to remain accessible. “That’s the real challenge we face,” he says.

One of Toth’s newest projects drew him and his colleagues to the Sinai desert. The St. Catherine’s Monastery, known formally as The Sacred and Imperial Monastery of the God-Trodden Mount of Sinai, was built at the order of Roman Emperor Justinian I in the 6th century, mainly to protect a trove of documents now second only to the Vatican’s massive collection.

Under the leadership of His Eminence Archbishop Damianos of Sinai, monks protect these manuscripts, other artifacts, and what many — including a steady stream of pilgrim travelers — believe was the actual burning bush from the Old Testament, just as they have for more than 1,400 years. The gongs of an ancient wooden bell still mark prayer times and meals. “It’s amazing. It’s one of those once-in-a-lifetime experiences to work there,” Toth says of the monastery, “It’s a ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ type thing.”

Until relatively recently, the pilgrimage to St. Catherine’s meant days on camelback. Today there is a paved road and an Internet connection, albeit a slow one. Toth and his colleagues traveled there in 2009 to test whether they could image palimpsests in such a remote location to preserve them, and to reveal hidden texts. They have now begun a multiyear project aimed at setting up a permanent system that the monks will be able to use to protect and study the monastery’s manuscripts, including at least 129 known palimpsests.

That first trip happened to coincide with the discovery of pages from an important historic document that had been stolen from Egypt, sparking new tensions over Toth’s team’s work. That’s one reason why there were government security officers with walkie-talkies outside St. Catherine’s thick ramparts. But the crew had been open with Egyptian antiquities officials about their plans. There would have been no way for such a conspicuous group to sneak into the facility anyway.

To reassure leaders, Toth says, “We talked to the Ministry of Antiquities over tea and everything died down, as is the way of the Middle East.” Still, they worked as quickly as they could. “We were trying to stay ahead of the various new authoritative decrees they were issuing to get everything done, get the data out and get ourselves out.” They then processed the data and returned copies of the manuscript images to the monastery for further study.

Team leader Mike Phelps, from the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library in California, thinks Toth will remain a major asset as the team navigates a range of political and technical challenges ahead. “Mike has boundless energy, he’s extremely enthusiastic, and he’s very generous with his time and knowledge,” says Phelps, who thinks Toth adds a dose of needed reality at times. “Part of his job is sometimes to scare us,” he explains, “to say, ‘I don’t think that’s going to come together like it should, so we need to step back and rethink procedures. That’s what Mike does.”

Provided the political situation doesn’t get too dicey, they’ll be returning to Egypt in December. Preserving the monastery’s manuscripts, some of which are so brittle they’ll crumble at a touch, is a primary goal. But there is a very real attraction in what will be revealed.

Images from the 2009 test run have already uncovered hidden text from at least nine languages and pages from a pre-Christian Greek medical text. There’s simply no way to predict what the monks and their partners will be able to find as work expands. Those pages could easily hold secrets equal to or surpassing the importance and excitement of Archie, Jefferson’s smudge or the Gettysburg Address fingerprint. Toth says, “We just really don’t know what we’re going to find.”

Mark Schrope graduated with a BS in biology. Based in Florida, he writes for such publications as Nature, Popular Science, New Scientist, The New York Times and Sport Diver. He is writing “The Blowout Experiment,” a book about the Gulf oil spill.

See thewalters.org for more information about the Archimedes exhibition opening on Oct. 16.