Byrd Barnette Tribble (’54) of Winston-Salem first saw Betty Holliday Waddell Bowman in Bostwick dormitory on the Old Campus in 1950. At the time Byrd Barnette was settling in for her first year, having selected Wake Forest not so much for her family’s formidable history dating back to founder Samuel Wait, but, truth be told, for her unbeatable discovery in perusing college catalogs that Wake Forest students needed only one year of physical education to graduate.

“I said, ‘Sign me up.’ I knew I would be lucky to get a C,” Byrd says.

In swooped Betty Holliday, a high school basketball player, a garrulous self-described Army brat who had lived all over the country, most recently in tiny Enfield, near Rocky Mount, N.C., where her career military father, Donald Van Holliday (’29), chose to retire. “Daddy was the colonel in the Army, but (Mother) was the general,” Betty says, describing a couple she loved dearly but who seemed to resemble a modern breed known as overprotective helicopter parents.

In other words, for Betty and Byrd, both only children and first-year college students, Wake Forest introduced them to intoxicating freedom, relatively speaking, and, for Betty, to something she had been missing all her life — the stability of a true and lasting friend. Until Wake Forest her constants had been her doll collection, her books and a Scottie dog, always a Scottie dog. Now and forever, she had Byrd.

Byrd recalls, “I remember first meeting Roommate, and she had been over at Raleigh at the Debutante Ball and had gotten presented and came in with orchids and flowers. I thought, ‘Hmm. How am I going to manage this?’ ”

Betty chimes in: “You can tell the difference in us just by talking — how she was raised to be an academic.”

Byrd concedes, “I’m sort of the straight man in this setup.”

This “setup,” I contend, from personal experience, is elemental to Wake Forest, Old Campus or “new.” For those who wish to tend them, Wake Forest cultivates enduring friendships for all of life’s seasons. The allegiance between Byrd and Betty is 61 years old and going strong.

It all started this way. They were assigned other roommates. Byrd’s kept going home on weekends, baffling Byrd, who was thrilled no end to plant herself on campus for two months solid. “We just gravitated to each other for whatever reason, I don’t know,” Byrd says of Betty. They “switched out” the other students and made Bostwick 313 their new home, a headquarters for pranks and hijinks. “I said, ‘Hello, Roommate,’ and she said, ‘Hello, Roommate,’ ” Byrd says, “and it’s been that way ever since.”

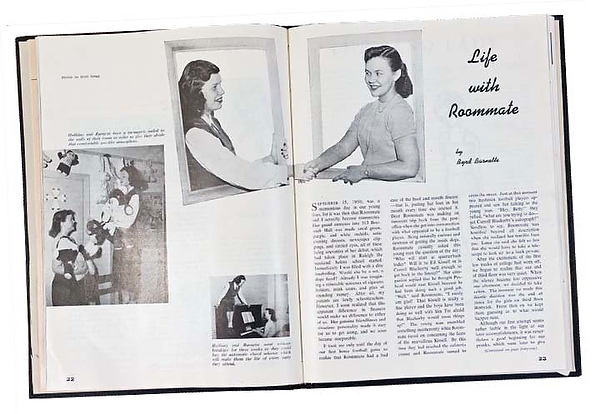

Betty Holliday Waddell Bowman, left, and Byrd Barnette Tribble (’54), right, appear in The Student magazine from the Old Campus in 1951.

Here’s where it gets tricky. Byrd is Roommate. Betty is Roommate. They address each other that way, the same way, six decades later, in Winston-Salem, where Betty lives a couple of miles from Salemtowne, Byrd’s retirement center destination after she left Tallahassee, Fla., in September 2010 as a widow. “Roommate and I don’t see each other every day, but we think of each other every day,” one will say. And the other will note their lunch plans nearby: “Roommate and I don’t go to fancy places,” preferring instead The Golden Apple on Robinhood Road.

“Roommate” might as well be the first name on each of their passports. Betty will be 80 on Oct. 3, and Byrd will be 79 on Nov. 15, but you would think otherwise on this day at Salemtowne. One minute they are sitting soberly (upholding, as Betty says, “senior citizenhood”) amid the framed colorful quilts of Byrd’s brick retirement cottage; the next they are transported to Wake Forest, N.C., — to its hamburger joints (“mystery meat,” says Byrd), curfews and magnolias — as rollicking schoolgirls of yore.

“We were there for the good and the bad,” says Byrd (left). “The miles haven’t seemed to matter to us.” Until she met Byrd at Wake Forest, Betty counted on her books and Scottie dogs to keep her company.

Dressed in black and wearing elegant gold jewelry, Betty helps set the scene when she takes from her sturdy straw bag adorned with a black ribbon a worn copy of the student literary magazine of the time, The Student.

“Oh, no!” says Byrd. She covers her lined face with her fine small hands. Why? I ask. “It’s so silly,” she says.

“It was the time. I’m not ashamed of it,” Betty says with conviction. “We didn’t have computers. We had people.” The article? “Life with Roommate.” The author? Byrd Barnette.

The Student had what Betty calls some “very solemn articles,” and its pantheon of editors included student literati, such as William F. McIlwain (’49), who went on to become editor of Newsday, and the late Harold T.P. Hayes (’48), who gained fame as editor of Esquire. Departing from perceived solemnity, The Student accepted the roommate piece that centered on pranks and included Byrd’s musing about Betty’s appearance on the scene with her debutante gear: “Would she be a sot, a dope fiend? Already I was imagining a miserable semester of cigarette holders, mink coats and piles of money.” Despite the differences in finances, Byrd wrote, “Her genuine friendliness and vivacious personality made it easy for us to get along, and we soon became inseparable.”

Says Byrd today, “They wanted me to expand on it because they said at this point it’s just a description of a bunch of tricks, which was true.”

“I guess that’s all they had to go on,” says Betty.

“I never did expand on it,” says Byrd.

The pranks: Greasing doorknobs with cold cream. Lighting smudge pots to smoke up the bathrooms. Sending secret-admirer letters. Waking hall mates at 3 a.m., exclaiming, “Say, aren’t you going to class? The first bell has already rung!” That one didn’t go over so well.

“We were famous,” says Betty.

“Infamous,” says Byrd.

“Well, whatever. I prefer famous,” says Betty. “We made people laugh.”

The roommates had two years together. They can recall the ambiance of the Old Campus and the fun they had flouting the rules. (Remember freedom?) Students needed parents’ permission to ride in cars or go to dances. They couldn’t date every night. There were curfews that required signing in and out of dorms. “I don’t know if I should say this or not,” says Betty:

“You’d sign out and go to the library, and you’d climb out the window.”

“You had to be resourceful,” adds Byrd.

Betty remembers how students liked to go on dates on the benches that were hidden by low-hanging magnolia branches. “You always had somebody with you, like double-dating,” she says.

“Not always,” says Byrd.

Betty is surprised by this revelation. “Not always?”

“No, it was mostly just the two of us,” says Byrd.

And therein, speaking of courting, arose a portent of things to come.

A few weeks after sophomore year, Byrd got a shocking letter from Betty. She had run off with her actor boyfriend to Durham. Betty Holliday and Bill Waddell (’52) had eloped. To this day Byrd speaks of it in a lowered voice: “Devastating.” The only ones more devastated were Betty’s parents, who managed a turnaround once the groom gave up acting and became a physician in Galax, Va.

The roommates went separate ways but not in spirit. Betty got her degree from the University of North Carolina in 1954. She was a Navy wife for three years and became a housewife; Byrd taught high school for a while and with her lawyer husband settled in Miami to rear their children. The roommates were apart, sometimes thousands of miles apart, but their friendship never wavered. It saw them through the birth of Betty’s two children and Byrd’s three, Betty’s divorce, Betty’s marriage to George Bowman, the decline of both sets of parents and their deaths, and the illness and loss of Byrd’s husband, Jim Tribble (’55), three years ago.

To nurture a friendship for six decades, Byrd says, “You have to want to.” Says Betty, “It’s not just ‘I’ll see you at the next reunion.’ ”

They have supported each other. They have visited each other’s homes on road trips. They have loved Wake Forest (“my first love,” says Betty), they have cared, and they have kept on laughing. “We only had two years. If I hadn’t got married, no telling what would have happened,” Betty says. “If we had had four years, we could have really been famous.”