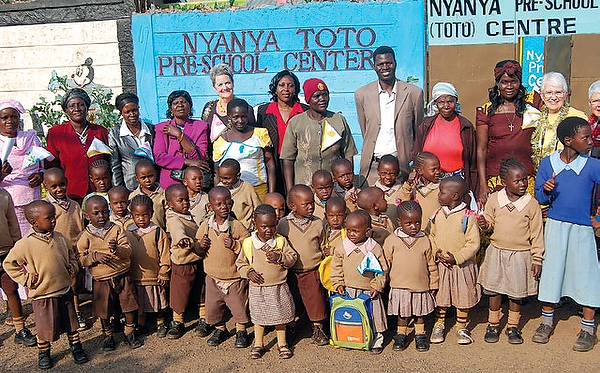

Niepold (back row, fifth from left) at a celebration with nyanyas and preschoolers in Kenya, July 2011.

It wouldn’t be wrong to say that I followed my brother his entire life. Dwight was my only sibling, two years older, and even in our small hometown of Lexington, N.C., I needed someone to show me which way to go, or, at least, which was the most interesting way. Eventually, I followed him right to Wake Forest.

Last summer, almost 50 years after we were both students here, I was walking down a narrow alleyway in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya, and memories of Dwight were everywhere. Dwight Pickard (’61) had died in March, and just a few yards in front of me a door said “Dwight’s Place Sewing Center.” I had named this tin-sided room for him because of his love and support of a nonprofit I had founded. The Nyanya Project teaches skills to African grandmothers (nyanyas) raising grandchildren orphaned by AIDS, and shortly after Dwight’s death, we in The Nyanya Project built this sewing center to generate income for a preschool we opened a year earlier. We were making a small dent in the struggles of AIDS orphans in Ken-ya, Rwanda and Tanzania being raised by women who are illiterate, widowed and forgotten by their own governments.

Our preschool and sewing center are located in the largest slum in Africa. As I stood there, surrounded by 42 small children, all laughing, they ran toward the new tin room with the sewing machines behind their school.

I beamed at the door with Dwight’s name on it and remembered being a small child and wanting to be like him. At age 6 or 7, Dwight would ride downtown with someone in the family, come back to our grandparents’ home, and a room full of relatives, including me, would sit spellbound as he told what happened when he met the automatic alligator down at Mr. Eames’ gas station. I wanted to be just like him. Telling stories, making everybody laugh.

So it was no surprise that I followed him to Wake Forest. Our grandfather, U.S. Rep. Charles Henry Martin, had graduated from Wake in 1872 and taught Latin and Greek here. Next was our father, Dwight L. Pickard, who had finished undergrad and law schools here in the late 1920s. Dwight entered in 1957. I followed soon after, and now my 14-year-old grandson, Aiden, wants to continue the legacy.

Wake Forest had informed our entire family. Everything about this campus had directed an impulse to think of others — then helped us put feet on our words.

Then-Dean Ed Wilson (’43) illuminated the need to honor truth. The late English Professor Elizabeth Phillips was the first woman I had known who spoke her own mind so unflinchingly. The late E. E. Folk (’21), also an English professor, repeated the dictum: “The only way to write is to write.”

And so I did. Dwight had majored in English. So did I. He had been editor of The Student magazine and asked me to write for it. I said I didn’t know how. He said, “Yes, you do.” I did. My freshman year, he told me that his fraternity brother, George Williamson (’61, P ’94), was organizing folks for civil rights demonstrations downtown and over in Greensboro. “Go help him.” “I don’t know how.” “Yes, you do.” I did.

Wake’s influence would gather momentum. I was active in Vietnam War protests, became a journalist and decades later, found myself sitting in an office in Tribble looking directly across the street into my old dorm room in Johnson. Now I am telling students: “The only way you can learn to write is to write.”

The Nyanya Project was born in 2007, and Wake Forest is inseparable from what we do. Students intern with me for the project. In 2008, six students, including Alphonso Smith (’08), a cornerback with the Detroit Lions, went to Tanzania to build a house for nyanyas. A sorority has baked pancakes for us, and the Office of Entrepreneurship has honored us. Ed Wilson, Betsy Gatewood and Sylvain Boko serve on our board.

Every fall, as I return to campus after weeks in Africa, I share how Pro Humanitate has taken root in a continent where hundreds of families no longer feel forgotten and new generations are being educated for the very first time.

I also see how my brother was my first teacher and thank heaven that I followed him here.

Mary Martin Pickard Niepold (’65) is a senior lecturer of journalism and 2009 Purpose Prize Fellow. She has written for The Philadelphia Inquirer, The New York Times, Associated Press, Scripps Howard and others. She was executive editor of Tricycle: The Buddhist Review and is currently working on “The Roots and The Light,” a book about African grandmothers and the Nyanya Project.