Editor’s note: this article was originally published in 2012. Faculty titles have been updated for 2016.

Seems like only four years ago we had a Leap Year. Because there are actually 365¼ days in a year and not 365, every four years February gets lucky with an extra day to keep calendars in sync. So with Feb. 29 on the horizon here’s a bit of quadrennial trivia with a Wake Forest twist.

Irish lore has it that St. Bridget and St. Patrick struck a deal to allow women to propose to men — one day out of every four years — on Feb. 29, or 2.29. How interesting that the official course description for Politics 229 reads, “examines classic and contemporary arguments regarding the participation of women on politics as well as current policy issues and women’s political participation.”

No year that is divisible by 100 can be a Leap Year unless it can be divided by 400. John Llewellyn, associate professor of communication and an expert in urban legends, says he learned this tidbit while listening to a Sherlock Holmes radio play. In “The Case of the Iron Box,” gold is to be awarded as an inheritance on a Leap Year birthday in 1900. When it is determined 1900 is not a Leap Year, the plot takes a nasty twist.

About the number 29. As a prime number, it has no divisors other than one and itself, notes number theorist Jeremy Rouse, associate professor of mathematics. Not only that, he adds, if you subtract six from it repeatedly, you get 23, 17, 11, and 5. All of these numbers are prime, too!

“The number 29 is also a prime number that is one more than a multiple of four,” says Rouse. “Every such number can be written as a sum of two squares in a unique way (29 = 5 squared plus 2 squared). Another number that shares this property is 27109 (the Wake Forest ZIP code), and 27109 = 78 squared plus 145 squared.” Who knew?

If you walk up 29 steps along the side of Wait Chapel you see this as you look up:

And this when you look down:

Worth a climb every four years.

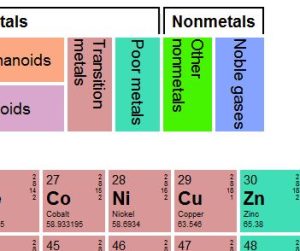

Those distinctively weathered blue-green rooftops on the chapel and other campus buildings? We owe them all to 29, atomic number of the element copper. “Copper’s conductivity is something we all plug into — literally,” says Ryan Swanson, campus architect in 2012.

Those distinctively weathered blue-green rooftops on the chapel and other campus buildings? We owe them all to 29, atomic number of the element copper. “Copper’s conductivity is something we all plug into — literally,” says Ryan Swanson, campus architect in 2012.

“But that’s not all; copper’s malleability and resistance to corrosion provide a roof overhead, pipes us clean water, coils to cool in summer and boils water to warm in winter. If it’s built to last it’s built with the 29th element.”

Browsing Level 2 stacks in the Z. Smith Reynolds Library, it appears 29 is “leapt over” as the Dewey Decimal call numbers go from 228 to 231.

And on the Reynolda Campus map building No. 29 is the Museum of Anthropology, where an exhibit titled “Art of Sky, Art of Earth: Maya Cosmic Imagery” is on display through May. The ancient Maya observed two calendar years, but neither bothered with a Leap Year.

Last but not leaped, should you feel the urge to recite verse on Leap Day, consider Shakespeare’s Sonnet No. 29, “No Fear:”

When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes

I all alone beweep my outcast state,

And trouble deaf heav’n with my bootless cries,

And look upon myself, and curse my fate,

Wishing me like to one more rich in hope,

Featured like him, like him with friends possessed,

Desiring this man’s art, and that man’s scope,

With what I most enjoy contented least;

Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising,

Haply I think on thee, and then my state,

Like to the lark at break of day arising

From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven’s gate.

For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings

That then I scorn to change my state with kings.

“The poem is about a long stretch of longing, so it might be an especially apt Leap Day sonnet since, as you can see, it’s one long verse sentence all the way through line 12,” says Olga Valbuena, associate professor of English. “It’s structured as if the poet-speaker would like to compress all the negative self-talk into the middle core of the sentence. Then with the turn (or volta) at line nine, he releases some of that insecurity by focusing anew on the beloved: ‘Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising, /Haply I think on thee . . .’ temporarily forgetting how insignificant he feels compared to the younger, hipper sort.”