They worked well past midnight on that April night in 1968; it was 2 a.m. when the three editors gathered up the copy and layout pages and climbed into the Blue Goose for the drive to the bus station on Marshall Street.

The Goose was a ’59 Chevy Biscayne, painted Wise potato chip-blue because Henry Bostic’s father was a Wise distributor and could score the paint for free. Bostic (’68) was driving, of course, and co-editor Ralph Simpson (’68) was along for the ride. So was Linda Brinson (’69, P ’00), the Old Gold & Black’s managing editor. She didn’t need to go, but like the editors, she’d stood at the back of Reynolda Hall earlier that night and seen the shadows of the fires burning near downtown Winston-Salem.

“I went,” Brinson remembers, “because I could — who was going to stop me? — and for the adventure.”

The campus paper was still printed in Nashville, N.C., in those days, the roughs bussed out early Saturday morning. They took the Blue Goose down Reynolda Road instead of Cherry-Marshall, which traversed the heart of the neighborhood rioting over the assassination, 32 hours earlier, of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., but they still collided with the National Guard. The soldiers at the checkpoints had rifles and serious questions about college kids who were out in the middle of the night.

The campus paper was still printed in Nashville, N.C., in those days, the roughs bussed out early Saturday morning. They took the Blue Goose down Reynolda Road instead of Cherry-Marshall, which traversed the heart of the neighborhood rioting over the assassination, 32 hours earlier, of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., but they still collided with the National Guard. The soldiers at the checkpoints had rifles and serious questions about college kids who were out in the middle of the night.

“They seemed surprised,” Brinson said, “but they did let us through.”

When she returned to campus that night, Brinson knew she’d have to track down the campus cop, who was invariably asleep at the power plant. In 1968, the women living in Babcock weren’t allowed their own key to the dorm. They couldn’t have cars until senior year or wear shorts on the Quad. That’s the way life was, Brinson reasoned, the burden of being a girl.

But for the moment, she was among equals, on deadline, a journalist skirting the war zone. If the rifles and the smoke were a little spooky, the freedom was exhilarating. She was from a small town and a backward high school, but suddenly she had the premonition, racing with adventure through the dark, that nothing was going to stop her.

But for the moment, she was among equals, on deadline, a journalist skirting the war zone. If the rifles and the smoke were a little spooky, the freedom was exhilarating. She was from a small town and a backward high school, but suddenly she had the premonition, racing with adventure through the dark, that nothing was going to stop her.

I recently read an interview in which the Nobel Prize-winning novelist Toni Morrison was asked why she had become a great writer, what books she had read, what method she had used to structure her practice. She laughed and said, “Oh, no, that is not why I am a great writer. I am a great writer because when I was a little girl and walked into a room where my father was sitting, his eyes would light up. That is why I am a great writer. That is why. There isn’t any other reason.”

— Donald Miller, “Searching for God Knows What”

On the question of why someone comes to write, I don’t know that many answers can match Toni Morrison’s. There’s no shame in conceding that a mélange of brick and mortar and magnolias might struggle to compete.

But when you ask around, when you push the various novelists and editors and literary all-stars to reflect on how Wake Forest figured in all the words that followed, their answers are unerringly similar and similarly inspiring.

The epiphany, it turns out, wasn’t an audience with A.R. Ammons (’49) or Maya Angelou. The unforgettable experience wasn’t the Wednesday afternoon poetry readings in Reynolda, the Friday nights on Pub Row or those Januarys with Dillon and the Guinness stout in Ireland. The creative catalyst wasn’t Elizabeth Phillips or Robert Hedin or John McNally or Bynum Shaw (’48, P ’75), bless their years in the trenches.

The literary tradition at Wake has been sustained, for generations, by something more: An open door.

The literary tradition at Wake has been sustained, for generations, by something more: An open door.

“I don’t mean to wax lyrical,” says Stephen Amidon, who has done just that in six novels since graduating in 1981, “but it was a kind of paradise for a writer. Almost any door that I knocked on was opened for me.”

When Amidon and a buddy, Jack Savage (’81), wanted to stage one of their plays, “The Fast,” Ed Wilson (’43) tendered the money that allowed them to present the existential drama in the University’s Ring Theatre. When Amidon suggested a senior paper on Sartre in 1981, Germaine Brée offered to introduce the two of them. When novelist James Dickey arrived on campus, Amidon escorted him out to the neighborhood bar.

“When you’re 18,” Amidon said, “you don’t know. That’s how I thought it was.”

At a great many universities, there is a pecking order, a waiting line, and a TA at a distant podium, advising you to play by the rules. “My dearest friend in high school went to Yale,” Amidon said, “and she basically didn’t see a professor until she was a junior. At Wake, the minute you hit the ground, you were face to face with (Jim) Barefield or (Donald) Schoonmaker (’60) or Alan Williams or Dillon Johnston. If you had a passion for theatre, you were immediately right there in the thick of it. There was no sense of being in the minor leagues, having to cool your jets for two years, to redshirt.”

When Malcolm Jones (’74), author of the memoir, “Little Boy Blues,” was a junior, he asked Germaine Brée, the celebrated professor of French literature, if he could spend a winter-term with her studying Albert Camus. “I thought I was too late,” Jones said. “It turned out I was the only one who asked her. And she said, ‘Yes.’ I spent a month studying Camus with someone who knew Camus. I’m not saying that’s unique to Wake Forest, but it was always my experience that it was easy to get to Germaine Brée or the other professors. There was never a line at the door.”

And there were few checkpoints where we had to flash credentials, pay our dues or beg for permission. When we were still clueless, Wake Forest allowed us to make waves and mistakes. When we were still searching for God knows what, the University encouraged us to push the limits, exploit our immaturity, even take our innocence abroad to London, Venice or Ireland.

You want to know why so many Wake grads became writers? Because when we walked into the room with a novel idea, someone’s eyes lit up.

On many occasions, that someone was the provost, Ed Wilson. When Dillon Johnston, who taught in the English department for 30 years, approached Wilson in 1976 about starting the Wake Forest University Press to publish the Irish poets whose work rarely crossed the Atlantic, Wilson stepped up with financial support and the University’s imprimatur. “He was encouraging, as he was with so many things,” Johnston says. “He was a person you could go to with ideas.

On many occasions, that someone was the provost, Ed Wilson. When Dillon Johnston, who taught in the English department for 30 years, approached Wilson in 1976 about starting the Wake Forest University Press to publish the Irish poets whose work rarely crossed the Atlantic, Wilson stepped up with financial support and the University’s imprimatur. “He was encouraging, as he was with so many things,” Johnston says. “He was a person you could go to with ideas.

He welcomed that.”

Wilson set a tone that the University embraced. Shane Harris — a ’98 graduate who won the 2010 Gerald R. Ford Journalism Prize for his reporting on national defense for Washingtonian magazine — was inspired by Shakespearean scholar Doyle Fosso, theatre director John E.R. Friedenberg (’81, P ’05) and the morning 15 students showed up on the first day of Maya Angelou’s class with drop-add slips … and she let every one of them in. But his defining Wake Forest experience was the freedom he found in writing for a sketch comedy troupe, the Lilting Banshees.

The Banshees specialize in uncensored satires and parodies of campus life; the troupe’s semi-annual shows are Wake’s version of “Saturday Night Live.” What Harris loved was the freedom he was given to test the limits of reason, humor and maturity.

“We were getting away with things you wouldn’t get away with at other schools,” Harris said. “It wasn’t because Wake Forest is smaller. It was just the way things were. No one got in the way. No one said, ‘No,’ or looked for a way to stop us. What defined me as a creative person happened outside the classroom. It was four years of living in an environment where you could take all kinds of risk. A comedy show? Sure. Why not?”

“We were getting away with things you wouldn’t get away with at other schools,” Harris said. “It wasn’t because Wake Forest is smaller. It was just the way things were. No one got in the way. No one said, ‘No,’ or looked for a way to stop us. What defined me as a creative person happened outside the classroom. It was four years of living in an environment where you could take all kinds of risk. A comedy show? Sure. Why not?”

Why not invite former President Thomas K. Hearn Jr. in for a cameo? Why not showcase the two guys who manned the grill at the Benson Center? Why not go for broke?

That is not to diminish what has long gone on inside the classroom at Wake, especially in the company of the Romantic poets or the interdisciplinary honors free-for-alls that welcomed Carswell Scholars to campus. “It’s not extraordinary for a fortunate student to have that catalytic encounter with a professor,” said Penelope Niven (MA ’62), the biographer of Carl Sandburg and Thornton Wilder. “That happens to a lot of people. But Ed Wilson doesn’t happen to a lot of people.”

Neither do Johnston, John Carter, E.E. Folk (’21) or Bynum Shaw, who — for 28 years — persuaded young newspaper writers that he could teach them more about journalism than they could possibly acquire while trapped in the J-school at Carolina.

“He was truly inspirational,” said Brinson, who survived that adventure in the Blue Goose to become the first woman to set her name on the masthead — as the editorial page editor — of the Winston-Salem Journal. “When he told us stories of how he covered the march across the bridge at Selma, he made you feel as if journalism was the most important thing about preserving the democracy and the pursuit of the truth.”

And by insisting that we learn how to think, not merely learn how to write, Shaw — like Folk, his legendary predecessor — dared many of us to carry that pursuit forward.

If Shaw had concerns about Brinson’s future in those male-dominated newsrooms — “He hoped I wouldn’t begin to curse” — he had a contagious faith in her talent: “Bynum believed I could do anything in terms of writing.”

Yet the freedom and access these writers discovered outside Tribble Hall is the blessing that has remained with them over the years. Jane Bianchi (’05), who edits Daily Health News, an electronic health newsletter in New York, remembers finding creative expression at the Old Gold & Black, the literary magazine, wind ensemble and as a DJ at the campus radio station. Laura Elliott (’79) flourished on Pub Row, as editor of The Howler, in the music department and theatre, and as the drum major on the football field.

The variety and stretching exercises were invaluable. “You have to be able to synthesize a lot of information from a lot of disciplines to write a difficult story,” said Elliott, a young-adult author perhaps best known for “Under a War-Torn Sky.” “You write about a thousand different topics, and the important thing as a writer is to be a constant learner and to enjoy that … and that all came from Wake Forest.”

The variety and stretching exercises were invaluable. “You have to be able to synthesize a lot of information from a lot of disciplines to write a difficult story,” said Elliott, a young-adult author perhaps best known for “Under a War-Torn Sky.” “You write about a thousand different topics, and the important thing as a writer is to be a constant learner and to enjoy that … and that all came from Wake Forest.”

Or as Niven said, “You have to live a certain depth and breadth and length of life before you have the audacity to write about another life.”

“What I remember about Wake Forest and the various communities that existed side by side is how permeable they were,” Malcolm Jones said. “If you wanted to try different things, you could.”

You weren’t boxed in. The door was invariably open. The door between disciplines in the Honors program. The door that led, after hours, to Michael Roman’s English department office or Dillon Johnston’s home. The door to the magical mystery tours at Casa Artom and Worrell House.

The doors that so often separate the community of writers from all the crazy things worth writing about … or the architects of the University’s ethic.

“I always wanted to transfer to the students the same thing I’d acquired at Wake Forest a generation earlier,” Wilson said. “I remember taking Shakespeare, the Romantic poets and Chaucer, on the one side, even as I read Virginia Woolf, D.H. Lawrence and James Joyce, at a time not long after the ban on bringing ‘Ulysses’ into the United States had been lifted. And as I sat around the table as a 20-year-old, and talked about Woolf and Lawrence, I realized I was entering into a world quite different than the one I knew in the other classes. I was being brought into the modern world.”

The invitation into that world was open to everyone at Wake Forest. Not everyone crossed the threshold or tested the lock … but the future novelists and essayists and playwrights did.

When they look back now, Malcolm Jones remembers a writing exercise on epitaphs with Jonathan Williams, who founded Jargon Press, in which Williams suggested they weigh each word as if it were meant to be carved in stone. “I’ve carried that humble lesson with me my entire life,” Jones said.

Laura Elliott can still hear Elizabeth Phillips — “unabashedly and wickedly smart” — lecturing on Emily Dickinson and “the idea that small observations carry the most profound meanings.” Dillon Johnston still revels in the semester in London when Worrell House boasted the best poetry reading series in the city.

Stephen Amidon still remembers what happened when he “tried to keep doing the things I’d done at Wake in the real world. I was crushed. If I wrote a play, no one wanted to put it on. If I wanted to work in journalism, no one answered my letters. That’s when I realized what a golden opportunity I’d been given as a writer.”

And Penelope Niven, the biographer, speaks for so many of us when she simply notes, “Wake Forest and I came together at a fortuitous time.”

When anything was possible. When adventure called and, the chapel lit up in our rear-view mirrors, we raced after it, convinced that no one could stop us.

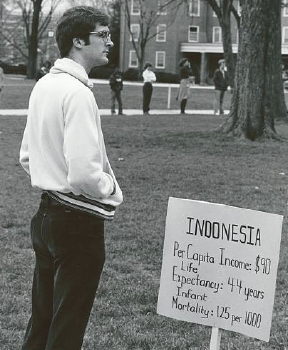

Photos courtesy Forsyth County Public Library Photograph Collection, the Wake Forest School of Medicine Dorothy Carpenter Medical Archives, Digital Forsyth Collection, and Winston-Salem State University Archives