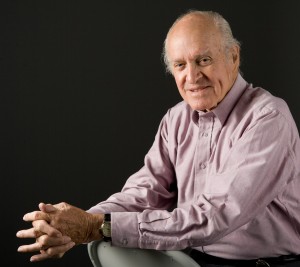

Weston P. Hatfield (’41), a past trustee who was one of Wake Forest’s most influential leaders, has died.

Weston P. Hatfield (’41), a past trustee who was one of Wake Forest’s most influential leaders, has died.

Hatfield died of lung cancer at his home in Winston-Salem on Oct. 19. He was 92. A celebration of his life will be Nov. 7 from 5 to 7 p.m. at Old Town Club in Winston-Salem.

“Wes was a great friend. He was a valued leader, adviser and supporter of his alma mater,” said President Nathan O. Hatch. “His keen intellect, progressive spirit and eloquence will be missed.”

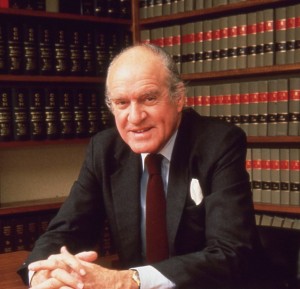

A longtime Winston-Salem attorney, Hatfield served three terms on the University’s Board of Trustees between 1977 and 1990 (1977-80, 1982-85 and 1987-1990). During his two terms as chair, in 1984-85 and 1988-90, Wake Forest grew in stature and increased its national reputation.

He presided over some of the most significant changes in Wake Forest’s history, including the University’s break with the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina, a major campus building program and the start of the University’s largest capital campaign at the time. “He was one of the most important men of his generation for Wake Forest,” said Provost Emeritus Edwin G. Wilson (’43), who first met Hatfield when they were both students on the Old Campus.

Hatfield is survived by four children: Anne Hatfield Weir (MBA ’76), Heidi Hatfield Karelis, Andrea Hatfield O’Leary and Weston Warren Hatfield; and 11 grandchildren including Howard Weir IV (’07), Lisa Weston Weir Mangiapani (’08) and Howard O’Leary III (’09). His wife of 59 years, Lisa Katerine Hatfield, died in 2008.

Condolences may be sent to the Family of Weston Hatfield, P.O. Box 5843, Winston-Salem, NC 27113. Memorial gifts may be made to the Salvation Army or the Weston P. Hatfield Fund, Wake Forest University, P. O. Box 7227, Winston-Salem. NC 27109. Read his full obituary and sign his guest book. Read more on Wes Hatfield in the Winston-Salem Journal.

“My father loved Wake Forest, and his life and work embodied the University’s philosophy of Pro Humanitate – giving back to the community,” Anne Hatfield Weir said. “He was so proud to have played a significant role in its transition from a regional Baptist school to a nationally ranked University.”

Hatfield served on the selection committee that tapped Thomas K. Hearn Jr. as Wake Forest’s 12th president in 1983. The two men — both born on July 5, but in different years — became close friends on the tennis courts and in board meetings. Hatfield worked closely with Hearn and other trustees to resolve the governance issue with the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina and a crucial shortage of academic and student-life space on campus.

During his first term chairing the board, he presided over the process that eventually resulted in Wake Forest breaking its governing ties with the Convention. Convention delegates turned down a plan in 1985 that would have given Wake Forest more authority to select its own trustees. A month later however, Wake Forest’s trustees decided to elect their own successors anyway. A year later Convention delegates approved a “fraternal, voluntary relationship” with Wake Forest and ended all formal governing ties.

Wilson said Hatfield played a key role throughout that process. “Much of the success of the agreement finally reached was a tribute to his legal skills, to his understanding of the problems and to his talents that enabled him to bring opposing sides together,” Wilson said.

An article in the Wake Forest Magazine in 1986 noted Hatfield’s “cheerful willingness to spend hours planning board strategy and questioning details in affairs the Trustees must deal with.” But it wasn’t a sacrifice to give his time to the University, he said: “It was a labor of true affection.”

Hatfield became chair of the board again in 1988. During his second term as chair, Wake Forest continued an ambitious building program – the largest since the move to the new campus – with Olin Physical Laboratory, the Benson University Center, Worrell Professional Center for Law and Management, the Wilson Wing of the Z. Smith Reynolds Library and an addition to Winston Hall, all built in the late 1980s or early 1990s. He also pushed for construction of what became Lawrence Joel Veterans Memorial Coliseum.

In 1989, Hatfield presided over the start of the $150 million Heritage and Promise capital campaign, which ultimately raised more than $170 million for faculty development, student financial aid and new buildings on the Reynolda Campus.

In 1989, Hatfield presided over the start of the $150 million Heritage and Promise capital campaign, which ultimately raised more than $170 million for faculty development, student financial aid and new buildings on the Reynolda Campus.

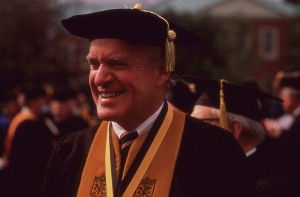

Hatfield left one other permanent mark on Wake Forest – he commissioned the Presidential Chain of Office, a goldplated necklace of medallions bearing the names of former Wake Forest presidents, that is now part of the academic regalia worn by the president at Commencement and convocations.

When Hatfield received the University’s highest honor, the Medallion of Merit in 1991, he was praised as a “true exemplar of heritage and promise. He helped to plan for Wake Forest a future of freedom and of growing national recognition which at the same time would preserve the values of the college he came to know 50 years ago.” He received an honorary doctor of laws degree in 1996 and the Distinguished Alumni Award in 1985.

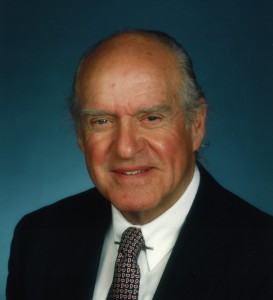

Friends remembered Hatfield as a gracious man and an eloquent writer and speaker, with an urbane and cosmopolitan manner, and deep intellectual curiosity. He loved music and was a talented singer and pianist. He had a wide range of interests, from medieval history to real estate.

He wrote an unpublished biography of Joan of Arc, a bestselling guide to commercial real estate investing and three novels: “Murder at First Baptist,” “The Governor’s Choice” and “Where There’s a Will.” He also wrote articles on the lives and musical theater of Gilbert and Sullivan. A short story, “The Barnstormer,” that he wrote after taking his children to an air show at the Smith Reynolds Airport in 1960 was published in The New Yorker.

A native of Hickory, N.C., Hatfield received a scholarship to attend Wake Forest. “One reason I’ve been so loyal to Wake Forest is my memory of how wonderful people were to me when I was in school there,” he said in a newspaper article in 2002.

He was a member of the debate team and Omicron Delta Kappa as a student on the Old Campus, and his leadership skills were evident even then, Wilson recalled. “He was one of the most eloquent and versatile young people I’ve ever known. He always spoke and acted with conviction and with passion. He was a formidable debater and orator, and those skills continued with him as long as he lived.”

Hatfield attended Harvard Law School, where his studies were interrupted by three years of service in the U.S. Army, 32 months of which were spent overseas. He landed on Utah Beach as a radio correspondent three days after the historic invasion of Normandy, and subsequently joined the army’s criminal investigation division. At war’s end, he was in Ansbach, Germany, responsible for the denazification of Upper and Middle Franconia; during this time, he met his future wife, Lisa Knueppel, a native of Hamburg, who was an interpreter for the American Military Government. The couple wed in New York three years later.

Hatfield attended Harvard Law School, where his studies were interrupted by three years of service in the U.S. Army, 32 months of which were spent overseas. He landed on Utah Beach as a radio correspondent three days after the historic invasion of Normandy, and subsequently joined the army’s criminal investigation division. At war’s end, he was in Ansbach, Germany, responsible for the denazification of Upper and Middle Franconia; during this time, he met his future wife, Lisa Knueppel, a native of Hamburg, who was an interpreter for the American Military Government. The couple wed in New York three years later.

After graduating from law school, he returned to North Carolina and eventually opened his own law practice in Winston-Salem. He was a judge on the old Winston-Salem Municipal Court from 1955-1958. He joined the North Carolina and American Bar Associations in 1947 and held numerous leadership roles in both organizations. As chairman of the ethics committee of the North Carolina Bar from 1982 to 1985, he led a subcommittee that rewrote the state’s legal code of professional conduct.

At the time of his death, he was of counsel to the firm of Hatfield, Mountcastle, Deal, Van Zandt and Mann.

Hatfield received Winston-Salem’s Distinguished Service Award in 1956. At various times, he served as president of the Chamber of Commerce, the Winston-Salem Symphony Association, Goodwill Industries and the Winston-Salem Arts Council. In 1947, he chaired a sub-committee which helped plan the ground breaking for Wake Forest’s new campus in Winston-Salem.