James G. “Jim” Jones (’55, MD ’59) didn’t come to Wake Forest to be a trailblazer. A Lumbee Indian who grew up on his grandparents’ farm in Pembroke, N.C, he simply wanted to follow in the footsteps of his hero, Albert Schweitzer, and become a medical missionary in Africa. It wasn’t until years later that he discovered he was the first Native American student to graduate from Wake Forest.

James G. “Jim” Jones (’55, MD ’59) didn’t come to Wake Forest to be a trailblazer. A Lumbee Indian who grew up on his grandparents’ farm in Pembroke, N.C, he simply wanted to follow in the footsteps of his hero, Albert Schweitzer, and become a medical missionary in Africa. It wasn’t until years later that he discovered he was the first Native American student to graduate from Wake Forest.

Jones, who turns 79 this month, never made it to Africa. Instead he became a national crusader for family medicine and a passionate advocate for delivering medical care to poor and rural communities.

“I gradually came to understand I hadn’t been divinely inspired,” he says of his decision in medical school to refocus his life’s calling closer to home. “Someone once said that I created my own mission field in eastern North Carolina.”

Jones also opened the doors for other Native Americans to attend Wake Forest, including his cousin, the late Lonnie Revels (’58, P ’82). Jones, Revels and Lucretia Hicks Dawkins (’10, MAM ’11), who founded the Native American Student Association, were honored in November at a ceremony that was part of the “Faces of Courage” yearlong celebration of 50 years of integration at Wake Forest. In 1962, after the Trustees voted to end desegregation, Ed Reynolds (’64) became the first black student to enroll.

A colleague once described Jones as a “giant in medicine in North Carolina.” A country doctor who started his practice in Jacksonville, N.C., Jones became one of the state’s most forceful advocates for establishing a new discipline called “family medicine.” He founded the family medicine program at East Carolina’s new medical school in the 1970s — and prodded UNC, Wake Forest and Duke to start similar programs — and chaired the department for two decades.

He used the bully pulpit of the presidency of the American Academy of Family Physicians in the ’80s to raise awareness of the need to train doctors for rural areas. And, as North Carolina’s top health-planning director in the ’90s, he warned of a coming health crisis and advocated greater accessibility and affordability for health care.

Nothing in Jones’ background suggested the influential role he would play in medicine. He was only 5 years old when his parents left him and his four brothers and sisters with their grandparents. “It turned out to be a blessing,” Jones says. His grandmother, a teacher in a one-room school, instilled in him religious and educational values and a strong work ethic.

He decided early on that he wanted to become a medical missionary after his high school biology teacher sparked his interest in medicine and a Baptist missionary his interest in mission work. “I was inspired when I was quite young,” Jones says. “I felt a strong urge to commit myself for service in the church or whatever God led me to do.”

He transferred to Wake Forest after two years at Mars Hill Junior College. He doesn’t know if anyone at Wake Forest realized he was Native American when he applied. It never occurred to him that his race might be a problem. “I wasn’t arrogant; I was just naïve,” he says.

He became active in Student Government — learning political skills that would serve him well decades later leading medical associations — and waited tables in Francis’ Grill in downtown Wake Forest. Other than one roommate who told “Indian jokes” — but there was nothing malicious about it, Jones says — he was treated well.

Despite a stellar academic record, Jones faced hurdles when he applied to Wake Forest’s medical school. He feared that he would not be admitted following what he calls hostile, racist questioning in his medical-school interview.

Decades later he learned that one of his professors at Mars Hill had strongly encouraged the medical school to accept him. It was an act of kindness he never knew about at the time, he says. He flourished in medical school and was elected class president two years.

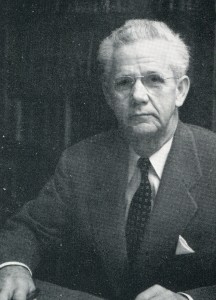

Half a century later, Jones still remembers the friendships with classmates and the mentoring in the college and medical school, especially by philosophy professor A.C. Reid (’17, MA ’18, P ’48) and medical school professor Wingate Johnson (1905, MA 1906). For much of Jones’ career, he kept framed photos of Reid and Johnson in his office.

“I was blessed at Wake Forest and Bowman Gray (School of Medicine) with faculty showing personal interest in me and guiding me,” Jones says. “Did they do that because I was different? I don’t know. Maybe it’s my naiveté. I think they saw a student that they wanted to help. The personal touches with faculty meant so much to me and have guided my life.”

Jones credits Reid with changing his life after the two got off to a rocky start. Registering for classes one semester, friends warned him against taking Reid for an ancient philosophy class. When he signed up for philosophy — back in the days when professors sat at long tables to personally enroll students — he told the professor he wanted anybody but Reid. The professor replied that he had good news and bad news: The good news was there was an opening in his class, but the bad news was that he was Dr. Reid.

His relationship with Reid didn’t improve when he received a C on his first paper. He recalls storming into Reid’s office demanding to know how he could receive such a poor grade. Reid’s answer has stuck with him: “Have you ever thought about thinking?”

Jones had to admit he hadn’t. “That was a novel idea. I had never truly learned the discipline of thinking. You memorize and give answers back without much thought.” Jones went on to make an A in Reid’s class, and they became close friends.

Forty years later, Jones received an unexpected call from Reid’s grandson, Dr. Lachlan Forrow, president of the Albert Schweitzer Fellowship program, based in Boston. The Schweitzer program supports approximately 250 graduate students annually who develop yearlong service projects to meet the health needs of underserved communities. Forrow had read about Jones’ affection for his grandfather Reid in Wake Forest Magazine and wanted to know if Jones would help him expand the Schweitzer program to North Carolina.

Jones helped launch the N.C. Schweitzer Fellows Program in 1994. Since then, about 350 fellows — including nearly 50 students from Wake Forest’s School of Medicine as well as law and divinity students — have served their communities, in much the same way as Jones.

“I’ve had a blessed life,” says Jones, officially retired on the North Carolina coast but maintaining an active schedule of conferences and public speaking. “Who would have thought a little boy abandoned on a little farm in nowhere, North Carolina, would have had a chance to do all this? I owe a lot of that to Wake Forest.”