At the beginning of the 20th century, R.J. and Katharine Reynolds became one of the region’s most influential couples in business and society, creating an estate that would one day be sacred ground to the Wake Forest community. Kahle Family Professor of History Michele Gillespie shares the following excerpt from her new biography, “Katharine and R.J. Reynolds: Partners of Fortune in the Making of the New South.”

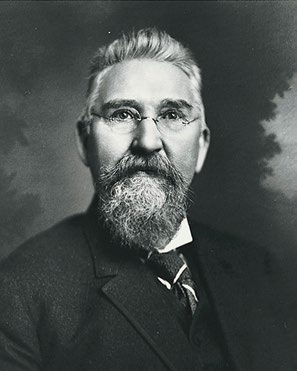

R.J. Reynolds, the founder and president of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, had never been a romantic. He preferred shrewd deals and hard living to sentimentalism. But his love for his first cousin once-removed, Mary Katharine Smith, thirty years his junior, proved deep and abiding. Kate’s decision to marry the famous captain of industry brought him great joy. Finding her spirited and opinionated, striking rather than beautiful with her black hair and sparkling eyes, Dick Reynolds loved his cousin with the abandon of a far younger man with far fewer responsibilities.

R.J. Reynolds, the founder and president of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, had never been a romantic. He preferred shrewd deals and hard living to sentimentalism. But his love for his first cousin once-removed, Mary Katharine Smith, thirty years his junior, proved deep and abiding. Kate’s decision to marry the famous captain of industry brought him great joy. Finding her spirited and opinionated, striking rather than beautiful with her black hair and sparkling eyes, Dick Reynolds loved his cousin with the abandon of a far younger man with far fewer responsibilities.

R.J.R. may have been deeply smitten but he was nobody’s fool. He had long skirted matrimony. His commitment to expanding his business through good times and bad had discouraged him from settling down. In Victorian fashion, his role as favorite son and bachelor caretaker for his extended family had also contributed to his postponement of a family of his own. But in 1903, Nancy Susan Reynolds, his widowed mother, died at the age of 77. Her death left him heartbroken, he explained in a letter to his young cousin Kate. “I have been so much absorbed in business that I feel much grieved from the fact of my … [not] spending more of my time with my dear beloved mother.” His eyes now opened to the passing of time, R.J.R. felt free to consider marriage. He immediately began pursuing Katharine, who did not mind his attentions. “Dear cousin,” she wrote R.J.R., whose company had turned the market town of Winston, North Carolina into a thriving New South city, “I was so sorry to hear of Aunt Nancy’s death.” Ten days later he invited his “Dear Cousin Kate” to join his nieces and himself on a trip to New York. “It will give me great pleasure to have you with us.”

R.J.R. may have been deeply smitten but he was nobody’s fool. He had long skirted matrimony. His commitment to expanding his business through good times and bad had discouraged him from settling down. In Victorian fashion, his role as favorite son and bachelor caretaker for his extended family had also contributed to his postponement of a family of his own. But in 1903, Nancy Susan Reynolds, his widowed mother, died at the age of 77. Her death left him heartbroken, he explained in a letter to his young cousin Kate. “I have been so much absorbed in business that I feel much grieved from the fact of my … [not] spending more of my time with my dear beloved mother.” His eyes now opened to the passing of time, R.J.R. felt free to consider marriage. He immediately began pursuing Katharine, who did not mind his attentions. “Dear cousin,” she wrote R.J.R., whose company had turned the market town of Winston, North Carolina into a thriving New South city, “I was so sorry to hear of Aunt Nancy’s death.” Ten days later he invited his “Dear Cousin Kate” to join his nieces and himself on a trip to New York. “It will give me great pleasure to have you with us.”

Why was R.J.R. so drawn to Kate? The most reductionist of interpretations would focus on their kinship. Marrying Kate Smith, the eldest daughter of his first cousin, meant he could keep his great wealth in the family, an age-old strategy for protecting fortunes. But if this had been his only criterion for choosing a bride, other cousins would have filled the bill much earlier. Kate Smith was more than kin. She was an exceptional young woman. R.J.R. respected her force of personality, and ultimately loved her for it. If R.J. Reynolds epitomized Henry Grady’s New South man, his wife-to-be embodied the next generation’s New South woman. Intelligent and determined, emboldened by familial affluence and the benefits of higher education, she used this set of attributes to secure considerable autonomy for herself, albeit through conventional means — first as an elite, single white woman in the early twentieth-century South, then as a married one.

Following their chaperoned trip to New York, R.J.R. invited Katharine to work for him as one of his personal secretaries, the only woman in that role. Her willingness to take on this position hints at her commitment to a more complex self-determination. Winston was a big city compared to Mt. Airy. But it was also a world in which young women of her race and class had been confined to narrowed feminine roles to justify the exclusion of black men from the body politic. On the national scene, women were just beginning to enter the professions, including teaching and nursing, but also as department store clerks and business secretaries. Though these new opportunities were increasingly available in the urbanizing South, they were not necessarily socially sanctioned ones for respectable young ladies. The prevailing racist ideology justified its public vilification of black men, and the removal of their civil rights as the best strategy for protecting vulnerable white womanhood. Young privileged white women’s presence as paid workers in public places complicated that argument.

Still, as R.J.R.’s secretary, Katharine could experience the new freedoms that came with employment while under the protection of the most important man in Winston. She discovered a youthful city in the throes of rapid demographic and economic growth, much of it due to the burgeoning R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. By 1900, over 17,000 residents called Winston, and the Moravian enclave of Salem right next door, home. Nearly a third, mostly African American, were employed in the tobacco factories nine months out of the year. The city embraced the ambition generated by the industry. In one week alone, the local papers bragged, the city had shipped out 800,000 pounds of plug (chewing) tobacco on 29 rail cars, breaking all world records.

Katharine also found a cultural milieu in the twin cities of Winston and Salem. High and low culture in the form of plays, concerts, operas and operettas, musical comedies, vaudeville and minstrel shows were commonplace. Silent motion pictures played at Nissen Park on summer evenings. Salem Female Academy and College had long embraced the importance of education, and women’s education at that. National black spokesman Booker T. Washington gave a public speech raising money for the R.J. Reynolds Slater Hospital for African Americans, with orchestra seats reserved for whites, the balcony for blacks. Katharine found herself in a vibrant new community, full of innovation and contradiction. Despite the novelty inherent in Katharine’s new home, with the thrill of modern capitalism at full tilt and plentiful arts to entertain her, she still had to consider her social standing. Protecting her reputation as a single working girl living away from home mattered. As another educated young woman who also worked in Winston politely noted about this period, “[I]t was not so generally accepted then as it is now for a girl to go into an office.”

Intelligent, hard-working and meticulous, Katharine began her wage-earning career on April 16, 1903, and quickly distinguished herself. The twenty-two year old not only kept the company accounts, but balanced R.J.R.’s personal accounts too, including his stock portfolio. A quick study, she parlayed her monthly salary into well over $10,000 worth of stock profits in less than eighteen months at a time when less than five percent of American men owned stock, and only a minuscule number of women.

Although only a handful of love letters from R.J.R. to Katharine have survived, they are remarkable in their sweetness and sincerity, and show a different man than the powerful public figure. After nearly two years in his employ, Katharine accepted R.J.R.’s marriage proposal, allegedly irritated that it had taken him so long to put forward. He replied by the next post,

My Dearest of All,

The 6thinst naming the 28th day of March as the day you will be my wife, gives me the greatest undescribable pleasure. … I feel that no one on earth … is blessed with a more noble earnest sincere lovely & sweeter or better wife than I will have in you. I love and respect you so much more than I ever did any one else, that I realy feel that I never before knew what real true love was, & it must be gods blessing in having me to wait for you & receive more happiness than earlier marriage would have given me.

R.J.R. , who rarely wrote anything down, trusted Katharine so implicitly he had poured out his heart, and with nary a concern for his lapses in spelling and grammar.

The wedding was held at 8:00 a.m. on a Monday morning in late February 1905 in Katharine’s parents’ home in Mt. Airy. The bride and groom entered the parlor, overflowing with fresh flowers, to the piano strains of Mendelssohn’s Wedding March and the Reverend D. Clay Lilly, minister of the First Presbyterian Church in Winston-Salem, presided over their exchange of vows. The newlyweds caught the next train to Greensboro, made their connection to New York, and headed for the Grand Tour on an ocean liner bound for Liverpool the very next morning. The two would share a thirteen-year partnership before R.J.R.’s death in 1918. They would conduct a far-ranging social life and, under Katharine’s direction, build a breathtaking estate and a model farm under Katharine’s leadership. R.J.R. would be credited with launching two of the most successful brands in history, Prince Albert Smoking Tobacco and Camel cigarettes. The two would provide leadership to a series of progressive reform movements and business innovations, and they would help drive one of the South’s best examples of rapid urbanization and changing race relations in the city of Winston-Salem. Together they two would become one of the New South’s most influential couples.