In 1970, Linda Carter Brinson interviewed Edward Reynolds for the July issue of Wake Forest Magazine. Reynolds had graduated in 1964 as the first black undergraduate at the College. In June 2012, Brinson and Reynolds met in Santa Barbara, Calif., for another interview for Wake Forest Magazine. At both meetings, the two alumni talked about Reynolds’ experience as the person who racially integrated Wake Forest and the impact it had on his life and career. This article draws on both interviews, 42 years apart.

I recognized Ed Reynolds (’64) the minute he stepped off the train in Santa Barbara. He’s the same dignified, shyly friendly man he was in 1970; the years have taken little toll on him. We exchanged greetings as if we’d parted weeks before, rather than 42 years, and headed for a hotel patio. He was eager to talk, obviously having reflected deeply on the remarkable life journey that brought him from Ghana to Southern California by way of Wake Forest in Winston-Salem, N.C.

By anyone’s standards, Reynolds can look back on his career with satisfaction. From Wake Forest, he went on to a master’s degree at Ohio University, Yale Divinity School and a Ph.D. in African history at the University of London. He’s an honored professor emeritus of history at the University of California, San Diego, where he’s garnered many teaching awards and academic honors since he arrived there in 1971. An esteemed scholar of African history, he’s the author of several books, including “Stand the Storm: A History of the Atlantic Slave Trade” (1985), an in-depth look at the Atlantic trade in slaves from Africa. He’s also a leader and sometime preacher in the Presbyterian Church.

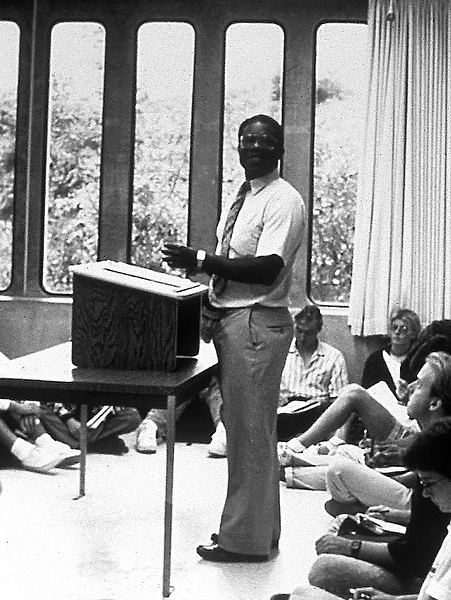

But Ed Reynolds has long applied a different set of standards to his life, a less quantifiable set. When we talked in 1970, he was teaching summer school at Wake Forest, where he had become the first black to graduate six years earlier. On the brink of finishing his dissertation and starting his career in San Diego, he said then that he wanted to be “a missionary to the United States,” promoting human relations in addition to his more formal teaching and preaching. Though he’s a modest man, Reynolds clearly — justifiably — thinks that through the years he has lived up to those goals as well.

To understand Ed Reynolds, you have to understand why he was willing to be the person to integrate the Wake Forest student body. Wake Forest’s end of the story is well known: With the backdrop of the sit-ins, sentiment for integrating the College was growing among students and faculty, although the administration appeared in no hurry to dismantle racial barriers. Organized into the African Student Program (ASP), activists hit upon the idea of contacting missionaries to recruit and finance a black African student who would be qualified as an international student. Harris Mobley, a Baptist missionary in Ghana, found Ed Reynolds. Reynolds’ initial application was rejected, so the ASP brought him to North Carolina in 1961 to attend all-black Shaw University in Raleigh while waiting for trustee action. After the College Board of Trustees’ historic vote in April 1962, Reynolds enrolled. He graduated in June 1964 with honors and a standing ovation.

When he talked with me in 1970, Reynolds said he came to Wake Forest because he “thought it would be very nice to have a part in bringing down the racial barriers in a major American university.” He did not plan to be an activist, he said, just to be himself, a young man and student.

After four more decades in the United States, in Santa Barbara Reynolds wanted to make a few other things clear.

For one, he may have been from Ghana, but he was more than qualified to attend Wake Forest. He recited the names of prestigious institutions where his grandfather, a Presbyterian minister, and his uncles and cousins studied: Basel, Oxford, Cambridge and Edinburgh. His relatives wrote a dictionary for Ghana, translated the Bible and penned hymnals and textbooks. Young Ed’s mentors were John Malloch, a Scottish Presbyterian missionary, and his young second wife. With their help, he was admitted to the Achimota School, a highly selective and prestigious secondary boarding school that has educated many of Africa’s leaders.

In fact, he said, some of his supporters wondered if an American education would be good enough. “You can’t be sure about American colleges,” he said, “and my dream was to go to Edinburgh. But this was a rare opportunity to do something that I thought was important. I had some uncertainty, but this is where faith comes in.“

“The whole racial integration issue was something that appealed to me — in terms of justice, equality and fairness,” Reynolds said. “It’s part of one’s basic belief and faith that there has to be justice and equality. One could go into a challenging situation and try to make a difference.”

Reynolds did not come to Wake Forest because it was his best chance to get a good education. He came because he wanted to fulfill the sense of mission instilled in him by his family and mentors, and because he admired the people at Wake Forest who were taking a stand for integration.

Looking back, he has many reasons to believe he made the right decision. For one, he did help advance the cause of integration at Wake Forest and at other Southern universities that followed its lead. He is quick to say, however, that American society still has a long way to go toward true justice and equality. “We have made some progress,” he said, “but I don’t think we are anywhere near where we should be. It seems to me that we lack the prophetic voices, the people of courage who demanded some of the earlier changes.”

He also got a fine education. “The academic programs were good. Wake Forest really prepared me for further studies,” he said. “The history program especially was excellent.”

And he made many friends among students and faculty. Not that everything was easy: There was the anonymous gorilla picture in the mail, and, more serious to him, the struggle to maintain his identity in a world where little was familiar. But he smiles enthusiastically when talking about his supporters. There was his roommate, Joe Clontz (’64), later a missionary in Togoland. “Clontz chose to room with me. He is a fun person to be with, but beyond that a very solid individual with a lot of strength. He was very protective and encouraging and made a lot possible for me.”

Reynolds knows that Clontz’ parents were not pleased with their son’s decision. “His parents might have had doubts, but his father owned a clothing store, and every couple of months he sent me clothes. Deep inside, the father realized the importance of what his son was doing,” he said.

Clothes were a problem both because he had little money and because he’d been used to wearing school uniforms. During the year at Shaw, Reynolds spent two weeks during December break with Wake Forest history Professor David Smiley (P ’74). When Smiley realized Reynolds had no overcoat, he gave him one of his World War II Army coats. “I thought it was nice and wore it,” Reynolds recalled.

Girls in the Baptist Student Union at Wake Forest were “like big sisters to me, and they would say, ‘Ed, your clothes don’t match.’ I had a hard time with this — I had on a shirt. I had on trousers. What were they talking about? I got to a place where I would try to buy all Navy blue jackets and dark ties so I would at least know I matched,” he said.

Names of other student friends came readily to his mind: Bill Brady (’65, MD ’70), Glenn Blackburn Jr. (’63), Frank Wood (’64, MA ’71), Barry Dorsey (’65), Ross Griffith (’65, P ’91). One friend even gave him a dollar a week out of his allowance. The black churches in Winston-Salem and the black people who worked in staff positions at the College also gave him great support. And his eyes glowed when he named the faculty, and, in many cases their spouses, who supported him. “These were learned people, and there was also a humanity about them,” he said. “What leaders: my good friend Smiley. Ed (’50, JD ’53) and Jean (’51) Christman. J. Allen Easley (P ’43, ’44, ’46), born in 1893 in South Carolina, but leading the debate on integration. Mark Reece (’49, P ’77, ’81, ’85). Chaplain Hollingsworth (’43). Professor Aycock (’26) and Lucille. Richard (’54, P ’81) and Betty May (’55, P ’81) Barnett. Mac Bryan (’41, MA ’44, P ’71, ’72, ’75, ’82), Charles Talbert and Phyllis Trible in religion. These were great people. Then there were young people like Tom Mullen (P ’85, ’88), enthusiastic and ready to really challenge you in terms of intellect. And Ed Hendricks, talking about how there were European colonials in North and South America, too. So many great people.”

As Ed Reynolds talked, our Wake Forest connection drew us together. These were the great people of my college days, too. I know exactly what he means.

“Deep within me, I think that I took a lot of my experience at Wake Forest with me, in terms of my understanding of what an undergraduate education was all about — the learning and the teaching, the intellectual exchange between professors and students,” he said.

The UC San Diego where he began teaching in 1971 was just beginning to develop a full university around the nucleus of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, using a residential college system like Oxford and Cambridge — or, as young Reynolds found, like Wake Forest. He flourished, inviting students to dinner, developing a mentoring program to help minorities and women pursue graduate studies, getting to know students as individuals, joining enthusiastically into the “lovely community” that reminded him of the one in Winston-Salem.

On this day in 2012, Ed Reynolds had work to do and a train to catch. I told him how good it was to see him again, and how interesting it is that he has both taught history and had an important role in history.

“Thank you,” he said, with that grin that still seemed a little bit shy.

The Impetus to Desegregate

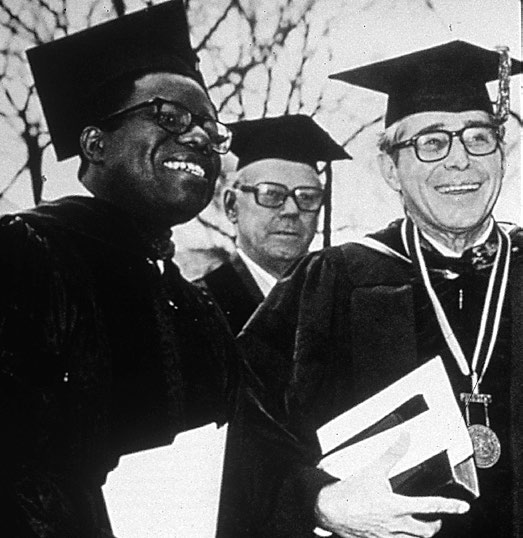

Ed Reynolds (’64) returned to Wake Forest last September to mark the 50th anniversary of integration as part of “Faces of Courage: Celebrating 50 Years of Integration,” a yearlong series of events.

During a program in Brendle Recital Hall, Reynolds recalled the support of his classmates, faculty and staff members when he arrived at Wake Forest in 1962. His roommate, Joe Clontz (’64), and other alumni, including Glenn Blackburn Jr. (’63), who headed the African Student Program, recalled that most of their fellow students welcomed Reynolds.

The program also included the premiere of a film, “The Impetus to Desegregate,” by documentary film graduate student Chris Zaluski. The film tells the story in the words of Reynolds, Provost Emeritus Ed Wilson (’43) and Chaplain Emeritus Ed Christman (’50, JD ’53). “If you assume what you’re doing is right … then you do it,” Christman says in the film. “And Ed Reynolds, that was the right thing to do.”

President Nathan O. Hatch presented Faces of Courage awards to Reynolds, Blackburn, Wilson, Ed and Jean (’51) Christman, Joe and Eva (’64) Clontz, Barry Dorsey (’65), Ross Griffith (’65, P ’91), Martha Swain Wood (’65), David Matthews (’62) and retired Dean of the College Tom Mullen (P ’85, ’88). He also presented Faces of Courage awards to the family of the late religion Professor G. McLeod Bryan (’41, MA ’44, P ’71, ’72, ’75, ’82), who was active in the desegregation movement, and to the Drayton family, Reynolds’ surrogate family in Winston-Salem.

The documentary film, a video of the panel discussion and more information on the award winners are available on the Faces of Courage website.

Linda Carter Brinson (’69, P ’00) spent nearly 40 years in the newspaper business, most recently as the editorial page editor of the Winston-Salem Journal. She writes and edits from her home in rural Stokes County and has a book-review blog.