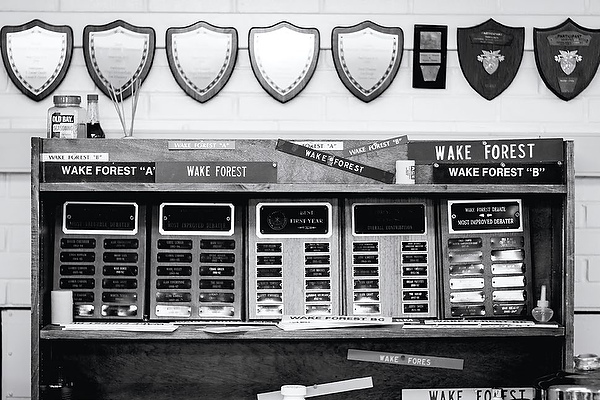

I’ve made my way to the top floor of Carswell Hall and into an attic-like room where the sole source of natural light is a large window overlooking Magnolia Quad. Along one wall are lockers; along another, trophies and plaques. At first glance it could be any classroom — students are seated around big tables, most wearing headphones and all focused intently on their computers.

But then the coffee pot catches my eye, alongside it a supply of pain relievers, allergy medicine, vitamins and cough drops. These over-the-counter clues remind me I’m not in just another classroom; I have entered the oratory outback of Wake Forest Debate, the squad room where a team of 28 student word warriors and their 12 coaches are already hard at work — a week before the semester begins — preparing for a new season of research, argument and persuasion. No wonder fatigue, headaches and scratchy throats happen here.

But then the coffee pot catches my eye, alongside it a supply of pain relievers, allergy medicine, vitamins and cough drops. These over-the-counter clues remind me I’m not in just another classroom; I have entered the oratory outback of Wake Forest Debate, the squad room where a team of 28 student word warriors and their 12 coaches are already hard at work — a week before the semester begins — preparing for a new season of research, argument and persuasion. No wonder fatigue, headaches and scratchy throats happen here.

So what am I — a writer who majored in conflict avoidance with a minor in podium panic — doing here? After all, the mere mention of debate suggests confrontation, and the team motto, “Think Hard, Talk Fast,” elicits a faint shudder. As I tiptoe to my observation point over in introvert corner, I know I’m here for a glimpse inside a diverse community “melting pot” whose members come from all over the country and represent a variety of perspectives on politics, race and gender. They have a reputation for being intelligent, inquisitive and sometimes, even quirky. I also know that I don’t fully appreciate the art of argument or its connection to a liberal arts education. What I don’t know yet is that this experience will teach me debate is about more than I ever imagined.

![]()

But let me back up a bit. To explore the Wake Forest Debate community my first stop is the Department of Communication’s Carswell Hall lobby, where glass cabinets showcase the history of debate through trophies and plaques, historical photos and a quote from Edwin G. Wilson (’43), provost and professor of English emeritus. “Long before we played football, edited publications, acted, or sang, in fact almost before we studied, we of Wake Forest talked,” it says.

That defining comment appeared in a 1940s Howler and puts into context the history of one of the country’s most revered college debate programs with its legacy of legends and loving cups. Wake Forest’s “talking” tradition dates back to 1835, just a year after the College was founded, and long before there were Greek organizations, Student Unions or myriad extracurricular and social activities to engage students outside the classroom. The history includes the first public debate between the Philomathesian and Euzelian literary societies in 1872, multiple championships and two National Debate Tournament titles in 1997 and 2008.

The program has flourished through the years, guided by visionaries such as George W. Paschal, H. Broadus Jones, A. Lewis Aycock, Franklin R. Shirley, A.C. Reid (’17, MA ’18, P ’48), Merwyn A. Hayes, Allan Louden (now chair of communication) and Ross Smith (’82). The Debate Hall of Fame honors stellar debaters who have gone on to careers including public service, law, academics, health care, think-tanks and politics.

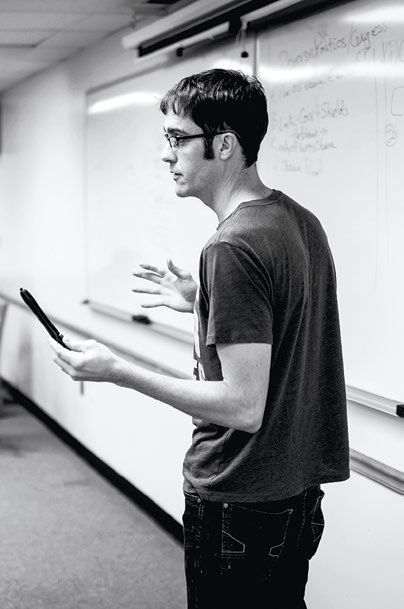

Back in the squad room I see these talkers are spending a good bit of time being quiet. Prolonged silence is punctuated by the tap of fingers on keyboards — there’s no more paper research in debate — as they intently surf the Web looking for information to support arguments for and against the energy-related policy resolution they’ll be debating this season, which culminates with the 2013 National Debate Tournament March 28-April 1.

Then, as the silence is broken by an impromptu back-and-forth on vegan versus vegetarian — complete with friendly barbs and laughter — I begin to understand why, when other students are outside tossing Frisbees on a warm summer day, debaters are holed up inside volleying terms like carbon capture and gasification. Debate’s culture is a passionate blend of camaraderie and competition in which personal success is valued second only to the success of the team.

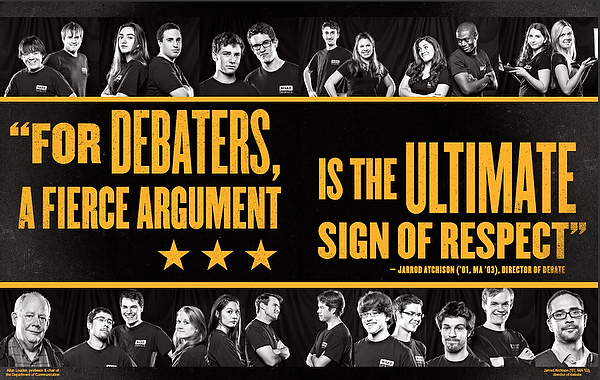

“For debaters, a fierce argument is the ultimate sign of respect,” says Jarrod Atchison (’01, MA ’03), a veteran of Wake’s team who returned “home” in 2010 as director of debate after three years in a similar position at Trinity University in San Antonio. “It means that you agree that another perspective is worthy of a rigorous analysis and you are willing to invest the time and effort into testing the idea. As a result, the debate community is largely defined by students who are passionate, intellectually curious and excited to engage in a battle of ideas rather than sitting around and assuming they have the whole world figured out.”

When we first meet, Jarrod is about to embark on a six-week summer recruiting trip. He’s looking for students with the raw intellectual talent to compete at the highest level — and who are ready to set goals and make the sacrifices it takes to win a national championship.

He’s both ecstatic and humbled to have been offered his dream job — a bittersweet opportunity brought about by the death of his mentor and friend, Ross Smith, in 2009. He met his wife, Becca Eaton Atchison (’03), on the team and, as many debaters do, he formed lifelong friendships including one with his debate partner, Justin Green (’99). Last fall he brought Justin back to Wake Debate as head coach.

We talk about debate culture and Jarrod says that while it’s easy to articulate the program’s longevity, the community itself is constructed year in and year out. “Debaters have lots of dorky things in common including being far more passionate about politics, philosophy, history and argumentation than their peers,” he says. “More fundamental, however, is the notion that things are not as black and white as they sometimes appear.”

Contrary to what some may think, debaters are not necessarily egotists. “Debate is a method of arriving at a decision, so when a community adopts debate as its central method of resolving conflict it actually reduces the role of ego, making it easier for people to change or to articulate their beliefs without resorting to personal attacks,” he adds.

Fast-forward to an 88-degree day just before the fall semester starts. I’m sitting at a table outside Z. Smith Reynolds Library with Drew Thies (’13) of Kansas City, Mo; Luke Sullivan (’16) of Aspen, Colo., Lauren Sisak (’14) and Joe Perretta (’14), both from Miami, Fla; and Lee Quinn (’15) of Birmingham, Ala. They are smart, amiable and psyched to be Deacon debaters. Even during our casual conversation their words are artfully chosen, delivered with cadence and confidence. I know if they tried they could persuade me today is a snowy day in December.

I ask what compels them to give up nights, weekends, holidays — and even come back to school early — to prepare for a new season of Wake Debate. It’s because debate is their passion — a “sport” at which they want to win. For Drew it’s not just about argument and persuasion — it’s about advocacy. For Luke, it means learning humility and resilience. For Lauren, it’s about mastering communication skills that will help her excel in the world of finance.

So what of camaraderie among debaters? “We definitely have a squad culture,” says Lauren, noting that later they are heading to a group cookout. “Between meetings, practice and tournaments, the group spends so much time together they’re almost like siblings.” Adds Joe, “What makes our relationships unique is that it’s not uncommon to tell war stories because we have similar experiences.”

We talk about the squad’s annual preseason retreat to the Blue Ridge Highlands of Virginia and the year they got a visit from 1997 National Debate Tournament co-champion Daveed Gartenstein-Ross (’98), now a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. “He is one of the most influential think-tank scholars in the world, and he came to a log cabin in Fancy Gap and slept on an air mattress,” says Lee. “We got to talk to him as much as we wanted about anything.” Adds Lauren, “I cannot think of another college debate team that has such a strong alumni network.”

At a squad meeting weeks later, Justin zips through the business items. The weekly shoutouts — debate’s equivalent of the attaboy/girl — follow and are acknowledged with snap-finger applause. There’s time for one brief flashback to a ’70s poetry slam (I’m undoubtedly the only one in the room who recalls the ’70s) and we’re on to serious stuff again — the National Earlybird Tournament Wake Forest is hosting that weekend. Debaters are reminded their responsibilities include tracking furniture and knowing how to locate extra toilet paper. “You are not volunteers,” says an assistant coach. And in this situation, I don’t hear any argument.

Walking to my car after the meeting I reflect on what I’ve learned in the last few weeks, namely that debate is about more than fast talking and persuasive argument. It’s about conquering challenges, building character and confidence, nurturing teamwork and responsibility — and most of all, self-discovery. Debate teaches lessons and provides opportunities that help students learn who they are and how they will lead examined and purposeful lives. In that regard it is a microcosm of the University community and the values that define Wake Forest.

I wonder, had I known back in the day what I know now, how the debate experience might have changed me. Maybe I’d have been more outspoken in meetings. Heck, I might even have dominated meetings. I might have grabbed that “notice me” seat instead of slinking to introvert corner. Maybe I would have engaged in spirited arguments, questioned authority or made my personal motto “Bring it on.” Perhaps, at the sound of my confident, persuasive voice, my children would have stood at attention, eager to listen and obey. But I suppose that last one would have been a stretch — even for debate.

Did you know this about debate?

- After a 1909 debate team victory over Randolph-Macon College in Virginia, a student writing for the 1910 Howler recalled the celebration this way: We look back with joy to Thanksgiving night, and we can still hear the old college bell ringing out, “Another victory won,” and the music of the pans as the howling mob woke up the town. Some of the speeches which certain members of the Faculty, clad in scanty apparel, made when called from their slumbers, still linger. Particularly do we remember Professor Carlyle’s speech in rhyme, as is his wont, which closed with this inspired couplet:

“While the moon is shining bright,

Now I bid you all good night.”

- Wake Forest’s long tradition of hosting high school debates began in 1917 with the first “Declamation Contest.” A $50 scholarship and a gold medal (reportedly worth $12.50) are the first prize; a gold pin, valued at $5, is second prize.

- As reported in a 1943 Old Gold and Black, Martha Ann Allen (’44, P ’80) joined the debate squad on a trip to Charlotte, becoming the first “member of the weaker sex ever to represent Wake Forest in any varsity debate tournament.”

- Franklin R. Shirley, who had a long-standing interest in the history of public speaking and rhetorical theory, became chair of the Department of Speech in 1963. Under his direction the debate program attracts national attention.

- Wake Forest offers a few competitive debate scholarships, including one named for Franklin R. Shirley, but most debaters are walk-ons.

- Two former mayors of Winston-Salem were Wake Forest debaters: the late Franklin Shirley and Martha Swain Wood (’65), who met her husband in the debate program.

- In 1988 Gloria Cabada (’88) became only the second woman ever to be named a National Debate Tournament Top Speaker.

- Brian Prestes (’97) and Daveed Gartenstein-Ross (’98) won Wake Forest Debate’s first National Debate Tournament title in 1997.

- Wake Forest hosted a “National Debate-In” on issues surrounding Sept. 11, 2001, and its aftermath.

- In 2008 Seth Gannon (’09) and Alex Lamballe (’09) won Wake Forest’s second National Debate Tournament title.