Producer, writer and actress Sona Tatoyan (’00) is tackling an ambitious project for her next film: An epic historical drama set against the backdrop of the mass killings of Armenians during World War I. The project is also intensely personal: Tatoyan’s family is from Armenia, and she holds dual U.S. and Armenian citizenship. Her father, Dr. Krikor Tatoyan (’73, MD ’77), is a general surgeon in Los Angeles.

Producer, writer and actress Sona Tatoyan (’00) is tackling an ambitious project for her next film: An epic historical drama set against the backdrop of the mass killings of Armenians during World War I. The project is also intensely personal: Tatoyan’s family is from Armenia, and she holds dual U.S. and Armenian citizenship. Her father, Dr. Krikor Tatoyan (’73, MD ’77), is a general surgeon in Los Angeles.

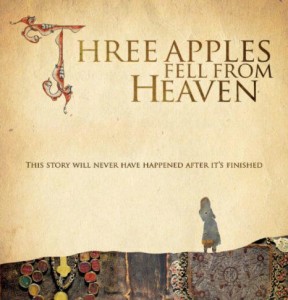

The film, “Three Apples Fell From Heaven,” is based on the award-winning novel of the same name by Micheline Aharonian Marcom. Tatoyan and her husband, Oscar-nominated screenwriter José Rivera (“The Motorcycle Diaries”), adapted Marcom’s novel for the film.

The novel takes place during what Armenians and many historians refer to as the Armenian genocide. Historians estimate that as many as 1.5 million ethnic minority Armenians were killed outright or died while being forcibly deported from present-day Turkey by Ottoman Turks between 1914 and 1917. The International Association of Genocide Scholars and more than 20 countries describe the killings as genocide. Turkey fiercely disputes that, maintaining that the deaths were the result of war and not a systemic attempt to eliminate Armenians. The United States does not officially recognize the killings as genocide; President Barack Obama has in the past promised to support the genocide charge, but last April he described the killings as an “atrocity,” stopping short of calling it genocide.

Tatoyan is the founder and president of Door/Key Productions. She lives in Brooklyn but is presently scouting locations for the film in Armenia and Turkey. She hopes to premiere the film at the Cannes Film Festival in 2015 — the 100th anniversary of the killings — followed by a wider distribution in the fall of 2015.

I know your parents are from Aleppo (Syria) but growing up, did you know much about your heritage?

I was born in Baltimore and spent some time in a small town in Alabama, but I mostly grew up in a little town called Portland in Indiana. My family moved to LA when I was 15. I did, however, spend almost every summer of my life with my mother’s family in Aleppo. We always spoke Western Armenian at home — it was mandatory. I was told the stories about the genocide from my mother’s aunt in Aleppo. To me as a child, the heritage and the culture were stifling: Old World, close-minded, conservative. All I wanted was to be a normal American kid! I didn’t want to eat Zaatar or hummus sandwiches — I wished I could eat peanut butter like everyone else. The first day of school when the teacher had to say your name for the first time was a real drag — always mispronounced and drawing attention to myself. Again, I just wanted to fit in.

You’ve written that as a first-generation Armenian-American, you didn’t feel like you belonged in either world. How did that affect your time at Wake Forest?

Well, at Wake Forest, I belonged to the theatre department. There I fit in … . And my best friends at Wake were always receiving Armenian history lessons from me after rehearsals. Drew Droege (’99) and Jeff Schoenheit (’99) had to listen to one too many horrifying genocide stories at my apartment after rehearsals!

You’ve also written that after having Maya Angelou for two classes, you felt a “kinship” with her. Was that a turning point in your life?

It was absolutely THE turning point in my life to embracing my dual heritage. Reading her autobiographies, then coming upon Peter Balakian’s book “The Black Dog of Fate” that summer between the two classes I had with Dr. Angelou, changed the trajectory of my life. I started to own my cultural inheritance in a way I never had. I started to see the value in being in this outsider/insider situation I had been my whole life. I started to realize there was actually something unique and special in this reality — and I was incredibly incensed at the continued denial of the genocide, both by the U.S. and Turkey, because of their political alliance. It was like a wake-up bell went off — a call to action in my life.

Were there other professors who inspired you?

Dr. Cindy Gendrich (in the theatre department) had a profound influence on me as a young actor. She mentored me on my senior directing project and introduced me to the work of José Rivera — who is now my husband and artistic collaborator.

How personal is this film to you?

My ancestors are survivors of this genocide. My great-grandfather was beheaded in Kharpert. My grandfather was born on Christmas Day in 1915 to my great-grandmother after this tragedy occurred. She somehow made her way to a refugee camp in Aleppo with an infant, walking. This project couldn’t get more personal. The need to tell this story for me is vital.

Can you give a quick synopsis of the film?

The film, in essence, follows a handful of characters whose lives intersect in various ways in the town of Kharpert as it is being dismantled during the years from 1914-1917. We see life before it starts, and watch the different course each of these lives takes as it’s happening. One of those characters is the real historical figure of Leslie Davis, the American pro-consul who was stationed in Kharpert at the time. His firsthand accounts of what happened were later published as a book called “The Slaughterhouse Province.” He tried to the best of his ability to help save as many people as he could, which was not many at all. The Turkish government was very good at outfoxing his efforts. In a lot of ways, it speaks to the American misunderstanding of the Middle East.

The title of the book “Three Apples Fell From Heaven” is based on an Armenian saying that three apples fell from heaven, one for the storyteller, one for the listener and one for the eavesdropper. Now you’re the storyteller; why did you want to tell this story?

The title of the book “Three Apples Fell From Heaven” is based on an Armenian saying that three apples fell from heaven, one for the storyteller, one for the listener and one for the eavesdropper. Now you’re the storyteller; why did you want to tell this story?

It’s actually also a Turkish saying. Both cultures share it. This is a story that hasn’t been told yet — not in this way. The film we’re making will be the first historical epic on the Armenian genocide. The term “genocide” was coined by Raphael Lemkin in the early 1940s to describe what happened to the Armenians during World War I and the destruction of the Ottoman Empire. It’s always been so ironic to me that what happened to us is why the word genocide exists … yet it is denied by the current government of the perpetrators and the U.S., and largely unknown in the world. It was the first genocide of the 20th century, a blueprint for the Final Solution.

You’re also playing one of the main characters, Lusine. Are there similarities with your great-grandmother Lucine?

There are. Lusine is pregnant when her husband’s head is brought back to her. She has to raise her son alone.

The director of the film, Shekhar Kapur (“Elizabeth” and “The Golden Age”), called your script the most beautiful script he had ever read. How could something that describes such horrific events be “beautiful”? And, on a personal level, I know you’ve been living with this project for years, how are you able to immerse yourself day after day in reliving these horrific events?

That is exactly what drew me to the book that this is based on — the beauty of the writing, all the while describing these horrific events, and the film does that in cinematic translation, gorgeous images of terrifying content. There is beauty in suffering as well, in loss, in being brave, in persevering and struggling for what you believe in, in survival. How do I immerse myself in this everyday? By crying a lot … by opening my heart to catharsis … by remembering why I am doing it — to tell the story of my ancestors, which hasn’t been told yet, not in this way — by knowing that this will somehow heal me in the long run. The only way out is through, and I’m in it.

You’ve said that by making this film you feel that you’re “turning poison into medicine,” that the telling of this story is a form of activism. What do you hope comes from the film?

I hope a dialogue comes from this film. I hope we are able to explore each other’s humanity through this film. I hope as a result of that, that there can be the beginning of healing for us as Armenians, to be heard, to have our catastrophe witnessed. That for the Turks, they, too, can come to terms with their past and get over the trauma that their denial has caused for so long. That those who have not been educated, inside and outside of Turkey, can have the opportunity to learn. And as crazy as it sounds, I hope for more love.