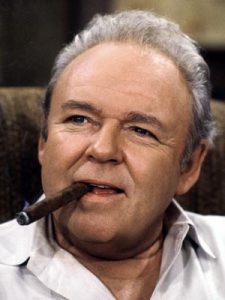

Long before he was Archie Bunker, Carroll O’Connor was a Demon Deacon. Thirty years before O’Connor played his iconic role as America’s favorite loudmouth bigot on the 1970s groundbreaking television show “All in the Family,” he was a student on the Old Campus.

Long before he was Archie Bunker, Carroll O’Connor was a Demon Deacon. Thirty years before O’Connor played his iconic role as America’s favorite loudmouth bigot on the 1970s groundbreaking television show “All in the Family,” he was a student on the Old Campus.

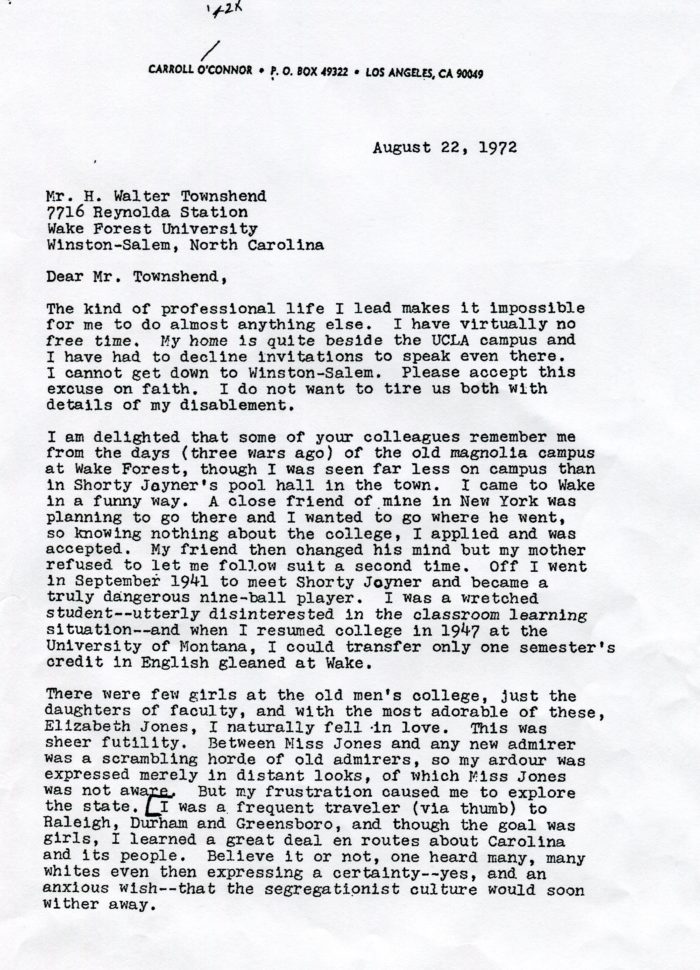

By his own account, he was a poor student who spent far more time in Shorty Joyner’s pool hall in downtown Wake Forest than in class. He dropped out before finishing his freshman year. But decades later he fondly recalled his time on the “old magnolia campus” in a letter to then-senior H. Walter Townshend (’73).

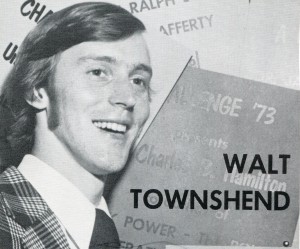

“All in the Family” was just beginning its second season in the summer of 1972 when Townshend invited O’Connor to participate in Challenge ’73, a campus symposium on higher education. “We found out that he had attended Wake and we thought that would be a great coup to get him to come speak,” Townshend said recently. “He would be a huge draw to Wait Chapel.”

Shorty’s, around 1943; no, that’s not Carroll O’Connor on the sidewalk. Note the sign on the window: Hamburgers and hot dogs for 5 cents.

Townshend, who was director of Challenge ’73, also invited Vice President Spiro T. Agnew, who declined. A number of others, including author and educator Jonathan Kozol, did attend the symposium in March 1973.

O’Connor turned down the invitation, but in a one-and-a-half page personal letter to Townshend, he offered an interesting glimpse into his time at Wake Forest. “I am delighted that some of your colleagues remember me from the days (three wars ago) of the old magnolia campus at Wake Forest, though I was seen far less on campus than in Shorty Joyner’s pool hall in the town,” he wrote to Townshend.

O’Connor grew up in Queens, N.Y., and had just turned 17 when he enrolled at Wake Forest in the fall of 1941. “I came to Wake in a funny way. A close friend of mine in New York was planning to go there and I wanted to go where he went, so knowing nothing about the college, I applied and was accepted. My friend then changed his mind, but my mother refused to let me follow suit a second time. Off I went in September 1941 to meet Shorty Joyner and became a truly dangerous nine-ball player. I was a wretched student – utterly disinterested in the classroom learning situation.”

Townshend, president and CEO of the Baltimore Washington Corridor Chamber of Commerce, has O’Connor’s letter framed and on display in his office, alongside letters from President Gerald R. Ford (P ’72) and Admiral William O. Studeman, former deputy director of the CIA and director of the National Security Agency. It’s an interesting conversation-starter, he said.

“I can almost remember the day I went to the post office and there was the letter from Carroll O’Connor,” he said. “I was disappointed that he couldn’t come, but because of who Carroll O’Connor was and more importantly the warmth and elements that he placed in the letter — talking about Shorty’s pool hall and not being fond of Tar Heels — it’s an interesting part of Wake Forest history and television history.”

In his letter, O’Connor also writes about the “few girls at the old men’s college” and the “sheer futility” of falling in love with the daughter of a faculty member. He took to the road, “via thumb,” to visit Raleigh, Durham and Greensboro. Decades before he played Archie Bunker and later the more tolerant Southern police chief Bill Gillespie in “In the Heat of the Night,” he learned some things about racial attitudes in the South.

“Believe it or not, one heard many, many whites even then expressing a certainty — yes, and an anxious wish — that the segregationist culture would soon wither away. … I knew a number of racists of the bird-brained wind-bag type but my larger impression of Carolinians (forgive me, but I am not fond of ‘Tarheels’) was not at all of a hard people, but of a very sweet people — probably trapped and confused, as James Baldwin believes, in their own incomprehensible American history.”

O’Connor dropped out of Wake Forest in the spring of 1942 before finishing his freshman year. He later attended the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy and served briefly aboard a freighter during World War II and then as a civilian seaman until the end of the war. He last visited the Old Campus in 1945, he wrote Townshend.

“I was a merchant seaman then — a fireman on an oil tanker, and we were lying useless in Miami with a broken boiler when Truman dropped his persuaders on the Japanese. I quit my ship and found a fellow who was driving to New York, and when we came through Wake Forest we stopped at Mrs. Wootten’s guesthouse on Route One. I roamed around the town that evening saying hello here and there, and I was touched and surprised almost to the point of disbelief that so many people remembered me – and not only remembered me, but welcomed me back, welcomed me home with love.”

O’Connor never again visited Wake Forest. Twenty-five years later, Bob Mills (’71, MBA ’80), assistant vice president for University Advancement, invited O’Connor to campus to visit the new Shorty’s, which had just opened in the Benson University Center in 1997.

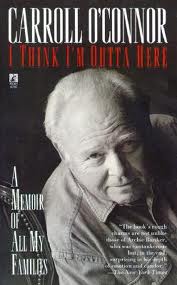

Hoping to spark O’Connor’s memories, Mills included a copy of O’Connor’s 1972 letter to Townshend. Mills never heard from O’Connor. A year later, he was surprised to see his letter to O’Connor and O’Connor’s letter to Townshend in O’Connor’s autobiography, “I Think I’m Outta Here: A Memoir of All My Families.”

O’Connor included both letters in an eight-page section that offered more details on his time on the Old Campus and hanging out with local “philosophers” at the railroad depot. His mother accompanied him on a passenger train when he came to Wake Forest in August 1941 to convince the dean to allow him to enroll, he wrote. (O’Connor doesn’t identify the dean, but it was probably Dean of the College D.B. Bryan.)

“My mother told me she would have to come down to Wake Forest with me to persuade the dean that three bad years and one good year (in high school) deserved, in my case, serious consideration, for they proved that a genius was finally germinating,” O’Connor wrote. “Somehow I knew how to sound plausibly like a genius, so Mama and I, a pair of city slickers, put one over on the kindly dean. I felt true remorse when, as the months wore on, he called me in once or twice and expressed his dismay that the germination had apparently aborted.”

When O’Connor returned to college years later at the University of Montana, only one credit in English transferred from Wake Forest. He graduated from Montana with degrees in drama and English in 1951 and later received a master’s degree in speech.