Nikolai Vitti (’00, MAEd ’01) is in a hurry. He’s on a mission to transform one of the largest school districts in the country. It’s an unlikely quest for someone who struggled mightily in school growing up in Detroit and who left Wake Forest after a year.

Nikolai Vitti (’00, MAEd ’01) is in a hurry. He’s on a mission to transform one of the largest school districts in the country. It’s an unlikely quest for someone who struggled mightily in school growing up in Detroit and who left Wake Forest after a year.

But eventually he returned to Wake Forest, completing undergraduate and graduate studies. Since then, he’s been on the education fast track to Harvard, New York, Miami and now Jacksonville, Fla. He was just shy of 35 years old when he was named the top education leader in Jacksonville last fall. He became superintendent of the Duval County Public Schools — the sixth largest school district in Florida and the 22nd largest district in the country — and moved with lightning speed on his vision to put teachers and students first. He moved aggressively to shift money and employees from the central administrative office to the schools, hire art and music teachers, reduce student testing, increase teacher training, and expand summer and pre-kindergarten programs.

Board members believe they’ve found a rising star in Vitti, who Fred “Fel” Lee, chairman of the Duval County board of education, says can take the school system from good to great. “One day, and I truly believe this,” Lee says, “you’ll see him as commissioner of a state (education department) or even in Arne Duncan’s job” as U.S. Secretary of Education.

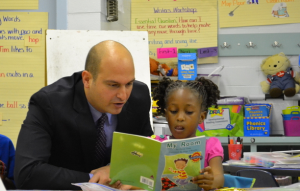

There’s plenty of work to do in Duval County first, Vitti said in mid-August, before beginning his first full academic year as superintendent. He’s focused on ensuring that the district’s 125,000 students have the same opportunities to learn and excel that he says Wake Forest offered him, a working-class kid with dyslexia. “What happened to me at Wake is what I want to happen,” he said. “The opportunity (for students) to be intellectual, to express yourself, to challenge yourself and come alive as a human being. I truly believe that can happen for every child with the right teacher and the right curriculum. That started for me at Wake.”

In the dozen years since he left Wake Forest — with an undergraduate degree in history and a master’s degree in education — he’s earned graduate and doctorate degrees from Harvard; taught at a 4,000-student high school in the Bronx; served as principal of a middle school in Homestead, Fla.; and held high-level positions at the Florida Department of Education and in the Miami-Dade County Public Schools.

***

Vitti’s ambition has been fueled by his belief that if he could overcome long odds to be successful, every child can. His enthusiasm and energy underscore a passion for children. “Our schools are a vehicle to a new life and an opportunity to open doors for children,” he told a Jacksonville television station last spring. That could sum up his personal story, too.

He grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Detroit, the son of a mother from Argentina and a father from Italy. He was raised by his mother after his parents separated when he was in third grade. His mother didn’t graduate from high school, but she earned her GED and taught her son the value of hard work and perseverance, Vitti said. His father, Antonio Vitti, moved away to join the faculty at Wake Forest, where he taught Italian from 1986 to 2010. (Antonio Vitti now teaches at Indiana University.)

Vitti recalled that his early school years were “painful.” He knew he was smart, but he struggled to read. Classmates made fun of him when he read aloud and mispronounced words. At Wake Forest he was diagnosed with dyslexia. (Even today he doesn’t like to read aloud.)

In high school his talent for football attracted the attention of small colleges. He turned down several scholarship offers to come to Wake Forest to reunite with his father and walk on the football team as an outside linebacker. After his freshman year — homesick and missing his high-school girlfriend — he transferred to a small college in Detroit.

He quickly realized that he’d made a mistake and returned to Wake Forest for spring semester. Then-football coach Jim Caldwell welcomed him back to the team, but the NCAA ruled that he would have to sit out a year before playing again. That turned out to be a blessing. “I realized my passion wasn’t football anymore,” Vitti said. “I fell in love with knowledge and books and academics.”

He worked in the Z. Smith Reynolds Library on Friday and Saturday nights, giving him plenty of time to read and study. He met his future wife, Rachel Burke-Thomas (’99) — a standout soccer player — in a sociology class, and he proposed to her six months later. (They have four children, ages 10, 8, 6 and 4.)

Vitti attributes his academic growth to professors Leah McCoy in education, Carolyn Matthews in English and Sarah Watts and Richard Zuber in history. “Part of my awakening was the opportunity — compared to a lot of the kids I grew up with — that education could make a difference to open up doors for kids like me and kids who have challenges even more profound than I had,” he said. “I saw my own awakening intellectually and realized how education could be used as a vehicle for social change and empowerment.”

He considered attending law school or becoming a documentary filmmaker before choosing a career in education and setting his sights on graduate school at Harvard. He did so poorly on his first attempt at the GRE that he shelved his plan. He taught in the New York City schools while studying to retake the GRE. It paid off when he did well enough on his second attempt to receive a nearly $200,000 Presidential Fellowship to Harvard. He likes to tell that story to students to show the value of perseverance to realize one’s potential.

***

After moving to South Florida in 2007, he took on some of the toughest assignments in the Miami-Dade County Public Schools, strengthening low-performing schools. He was chief academic officer for the Miami-Dade schools when he was named superintendent in Duval County.

After moving to South Florida in 2007, he took on some of the toughest assignments in the Miami-Dade County Public Schools, strengthening low-performing schools. He was chief academic officer for the Miami-Dade schools when he was named superintendent in Duval County.

Lee, the board chairman in Duval County, said the board was searching for a transformational leader when it hired Vitti. “We knew he was capable of doing it, but your people and system have to be prepared because he’s willing to move quickly. He’s a dynamic, aggressive, thoughtful, highly intelligent guy who really wants to take care of children.”

Even as other school districts around the country struggle financially, Vitti has funded a number of new initiatives through the district’s $1.7 billion budget for this academic year, using a zero-based budget approach and challenging how every dollar is spent. Under a previously negotiated agreement with the Duval Teachers United, the budget includes a “step” increase for teachers, based on years of experience, providing an average salary increase of about $827 per teacher.

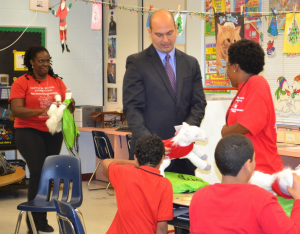

Vitti has cut 300 administrative positions while adding reading teachers, a disciplinary dean at each school and math coaches at underperforming schools. Security guards or police officers are now in all 183 schools. He’s increased teacher-training programs, expanded the district’s Pre-K programs and started a Parents’ Academy to increase parent engagement. The New York Times featured the district’s expanded and revamped summer school program.

Much of Vitti’s focus has been on “developing the whole child” by adding art and music teachers at each school. He recalls being exposed to art for the first time during an art history class at Wake Forest. “I was the kid who didn’t get that growing up. My mind was like a firecracker; it just lit up,” he said. “School shouldn’t just be about reading a passage and answering A, B or C. It should be about developing human beings. We have lost sight of what education should be about.”

Vitti is praised for being accessible and honest with teachers, said Chris Guerrieri, a veteran Duval County teacher who writes a blog focused on education issues. Guerrieri hasn’t agreed with everything Vitti has done, but he has been largely supportive on his blog. “He has an infectious way of making one feel both optimistic and enthusiastic about the direction the district is going,” he wrote recently.

Vitti’s most controversial decision has been replacing about 30 percent of the district’s principals, a move some parents criticized. As the new school year opened, he asked parents to remain patient as his plans unfold. He realizes that rapid change can cause angst and uncertainty, but he said his frequent visits to schools keep him moving forward. “When I go into a school and walk into a classroom and see children learning, it all becomes worth it,” he said.