Why would an architectural historian spend more than a decade writing a book on, of all things, the architecture of American ski resorts?

Why would an architectural historian spend more than a decade writing a book on, of all things, the architecture of American ski resorts?

I’ve wanted to ask Margaret Supplee “Peggy” Smith that ever since I heard years ago that she was writing such a book. I’m one of the many students who fell in love with architecture in her seminal course on modern architecture. Smith retired as Harold W. Tribble Professor of Art in 2011 after 32 years at Wake Forest.

To her legion of alumni fans, she was our ever-enthusiastic and engaging mentor as we discovered Frank Lloyd Wright, Phillip Johnson, Miles van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. In the basement of the Scales Fine Arts Center, we explored Fallingwater and Farnsworth; the Chrysler building and the Johnson Wax building; the Guggenheim and the Pompidou Center. But she never once mentioned A-frames, rustic lodges, luxury condos and faux Alpine villages that make up “ski resorts.”

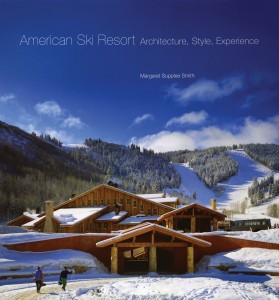

She makes up for that in her lavish new book, “American Ski Resort: Architecture, Style, Experience” (University of Oklahoma Press, 352 pages), that meticulously traces the architectural evolution of ski resorts from the 1930s to the 1990s. She presents a compelling case that ski resorts are a distinctly American type of architecture and one worthy of study. It’s just what you’d expect from Smith: to draw you into something and leave you captivated.

But it turns out that Smith once had the same question that I had, she told me when we sat down in a quiet nook of the Z. Smith Reynolds Library to discuss her book. For most of her career, she blissfully overlooked the architecture in mountain villages as she pursued her favorite pastime. As she explained in the book: “I had long ago come to terms with separating what I did for a living — architectural history — with what I did for recreation” (that would be skiing).

She began the long journey that led to “American Ski Resort” when she turned a critical architectural historian’s eye to studying how and why ski-resort communities developed. It needs to be pointed out first that it’s not a book about skiing — “the physical experience of skiing downhill,” as “swell” as that is, she writes — although the history of skiing is certainly a part of the story.

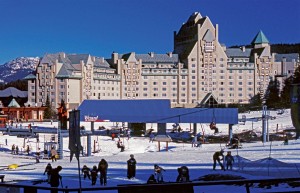

It’s actually two stories in one. The first is the evolution of ski resorts: from modest beginnings as rustic cabins and unpretentious lodges in the 1930s; to second homes for the newly upwardly mobile middle class pursuing the good life in the postwar period when skiing exploded in popularity; and finally to supersized postmodern vacation homes and corporate-owned, carefully planned mountain villages offering a “total” vacation experience in the 1980s.

Smith tells the often-intriguing stories behind the founding of such familiar resorts as Aspen, Deer Valley, Snowmass, Sun Valley, Sundance, Stratton, Squaw Valley and Vail. North Carolina’s infamous Sugar Top condominium, built atop a flattened Little Sugar Mountain, even merits a mention; its construction sparked stronger environmental laws.

The backstory is the increasing popularity of skiing and other recreation activities amidst social, economic, environmental and cultural shifts. In other words, ski resorts didn’t happen in a vacuum; many forces influenced the choices architects, builders, developers and homeowners made. “It’s another way of understanding the American experience — from the ski industry’s start in Depression-era work projects, to the expansive postwar boom in recreation and rise in disposable income, the environmental pushback in the 1970s, and the overreaching hubris of the 1980s and 1990s,” she writes.

Smith considers herself an intermediate skier who came late to the sport. Even though her parents had an A-frame (dubbed Chateau Buttercup by her mother) in Mount Snow in Vermont, it wasn’t until after she and her husband, Jackson, moved from Florida to Boston that a single afternoon of skiing on Mount Snow hooked her to the “pleasure of skiing down the mountains.”

It would be another 25 years before she took her first skiing vacation out west, to Snowmass, Colo. On that 1994 trip, Smith saw for the first time that there was rhyme and reason, and yes, architecture, to the planning, design and construction of ski resorts. The eastern resorts where she had skied for decades were developed in hodgepodge fashion; the West felt different.

“I felt a logic in the resort planning that reminded me of design principles I regularly taught in modern architecture classes,” she writes. “I saw design ideas of the German Bauhaus, urban planning concepts of Le Corbusier, site sensitivity characteristics of Frank Lloyd Wright and postwar consumer capitalism transplanted to the American Rockies.”

Before she could begin that project, she had to complete her book on “North Carolina Women: Making History” (University of North Carolina Press, 1999), co-authored with Emily Herring Wilson (MA ’62). After a dozen years working on that book, she was eager to explore new territory. The architecture of ski resorts was completely uncharted. A couple of historians study ski history and the environment, but no art historian had ever studied the subject in depth, Smith told me.

Before she could begin that project, she had to complete her book on “North Carolina Women: Making History” (University of North Carolina Press, 1999), co-authored with Emily Herring Wilson (MA ’62). After a dozen years working on that book, she was eager to explore new territory. The architecture of ski resorts was completely uncharted. A couple of historians study ski history and the environment, but no art historian had ever studied the subject in depth, Smith told me.

She was fortunate that many of the architects and major players were still alive and willing to be interviewed. Many of them were expert skiers; some had trained at Bauhaus and Taliesin. She includes biographies of more than 100 ski resort architects and landscape architects, which offer interesting tidbits. For instance, Harry Weese, who designed vacation houses in Vail, Aspen and Snowmass, also designed the Washington, D.C., metro system.

Smith actually finished the book five years ago and delivered the manuscript to her New York publisher on the September day that Lehman Brothers’ collapsed, sending the economy into recession. Terrible timing for a luxury book. The publisher balked at putting the money into developing the book that Smith was envisioning, and author and publisher soon parted ways. Two years later, she found the University of Oklahoma Press, which had never published an architecture book before but supported her vision. The wait was worth it.

Even if you’re not an art historian or a skier — and I’ve never been anywhere near a ski resort — Smith has written a thoroughly readable, lively book about architecture uniquely found in the mountains of New England, the Rocky Mountains and the Far West. When you finish reading the book, you might ask as I did, “Why hadn’t anyone thought of studying ski-resort architecture before?”

Starting with the gorgeous cover — featuring Deer Valley Resort’s Snow Park Lodge — the book is visually stunning, filled with more than 200 color and historical photographs, vintage posters and magazine covers, and architectural drawings, set in a crisp layout.

It’s a hefty book — 260 oversized pages, not counting notes and architect biographies — but fascinating details keep you reading ahead. Who knew, for instance, that veterans of the U.S. Army’s 10th Mountain Division, which trained in the Colorado Rockies and saw combat in the European Alps during World War II, played a major role in increasing skiing’s popularity in the postwar period? Or that you could buy a pre-fabricated A-frame house, complete with yodeling balcony, for about $3,000 in the 1960s? Or that former President Gerald R. Ford (P ’72) bought the first residential building site in then-struggling Beaver Creek in 1979?

Following our conversation, Smith had one final lesson to share. “The thing that is so great about architecture is that once you learn a few basic things and a modest appreciation, you are able to apply them for the rest of your life. No one can escape architecture — it is constantly around us.” Even on ski slopes.