In 1933, nine black teens were charged with the rape of two white women on a train in Jackson County, Ala.

They became known as the Scottsboro Boys, and history would go on to determine they had been falsely accused, wrongly convicted and punished for a crime they did not commit.

All the Scottsboro Boys served prison time; convictions against five were overturned and the charges dropped in 1937 by the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles, and a sixth was pardoned in 1976. Recently, at a historic hearing on Nov. 21, the remaining three received justice when the board voted to posthumously pardon them, a gesture made legally possible in large part through the efforts of Arthur Orr (’86), an Alabama attorney and state senator.

Orr helped draft and sponsored legislation — unanimously approved last spring by both the state House and Senate — to allow the parole board to grant posthumous pardons in cases with elements of racial and social injustice. The pardons essentially absolved the men of criminal misconduct and closed what The New York Times described last week as “one of the most notorious chapters of the South’s racial history.”

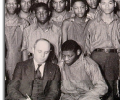

The Scottsboro Boys were represented by chief defense attorney Samuel Leibowitz. (Bettman/Corbis)

Orr grew up in Decatur, where the second round of trials were held, and he said the pardons were simply the right thing to do. “Unfortunately they’ll never know about it,” said Orr, whose personal commitment to social justice and serving those in need fueled his passion to right a wrong.

Sheila Washington, who founded the Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center in Scottsboro, began a campaign to seek pardons for the men in 2009. She learned that while Alabama officials were willing to consider pardons, they lacked the legal mechanism to grant them posthumously. Her campaign led her to Orr, and he took up the cause.

“We can’t change history, and I’m not suggesting we try,” he said, “but if there is something we can do, why not? Rather than saying we don’t have a posthumous pardon, fortunately we were able to change things.”

As one of Wake Forest’s more than 200 alumni Peace Corps volunteers, Orr spent 1989-91 in Khanbari, Nepal, after completing his law degree. He taught children and trained teachers in a one-room, dirt-floor structure and lived primarily off rice and lentils twice a day. He has also served Wake Forest as president of the Alumni Council.

A march on Washington in May 1933.

The pardons represent a cathartic moment for Alabama, said Orr, who was busy last week giving national and international media interviews as well as hearing from Scottsboro Boys’ family members who were gratified by the pardons.

“We cannot go back in time and change the course of history, but we can change how we respond to history,” he told The New York Times. “This hearing marks a significant milestone for these young men, their families and our great state by officially recognizing and correcting a tremendous wrong.”