With Cold War tensions between the United States and Soviet Union escalating in the early 1960s, President John F. Kennedy encouraged Americans to construct fallout shelters in case of a nuclear attack.

In early 1962, Wake Forest’s College Committee on Civil Defense followed the president’s lead and took action to help faculty and students survive doomsday. The committee recommended preparing fallout shelters to accommodate up to 3,000 people to shield “students and staff from nuclear fallout should such protection become necessary,” according to an article in the Old Gold & Black.

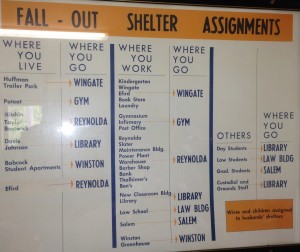

Shelters were prepared in the basements of Reynolda Hall, Reynolds Gym, the Z. Smith Reynolds Library and five other buildings, and stocked with enough water, hard candy, tins of crackers and sanitation supplies to last for 48 hours, when radiation levels were expected to be at the highest. Signs designating shelter assignments for students, faculty and staff were posted around campus. Wives (and children) were assigned to their husband’s shelter.

Shelters were prepared in the basements of Reynolda Hall, Reynolds Gym, the Z. Smith Reynolds Library and five other buildings, and stocked with enough water, hard candy, tins of crackers and sanitation supplies to last for 48 hours, when radiation levels were expected to be at the highest. Signs designating shelter assignments for students, faculty and staff were posted around campus. Wives (and children) were assigned to their husband’s shelter.

In the event of a pending attack, a siren on the water tower would alert the campus. Students were told they should grab personal items and toiletries and hurry to their assigned shelter, following the directions of student wardens in each dormitory. Student and staff teams in each shelter would be equipped with radios to communicate with the outside world and radiation-detection equipment to determine when it was safe to venture outside. “Best estimates are there will be at least 15 minutes warning, but more probably 30 to 60 minutes,” before an attack, according to the OG&B article, written by Adrian King (’64).

Living under the threat of nuclear annihilation was one thing, but the shelter signs were more than some students could bear, and some of the signs were ripped off campus buildings. In an editorial in the OG&B in March 1962, Charles Osolin (’64) wrote that that the signs were more horrifying than reassuring and argued for more efforts to erase “the threat of nuclear war, either through the abolishment of atomic weapons or through the easing of international tension.”

“He who goes all out to prepare for atomic war provides the Communists with a propaganda boost and may even be helping convince them that they would be able to win such a war,” Osolin wrote. “We must not let the bomb pervade our thoughts and work on our minds to the point where we begin to wonder if it may not be better to be Red than dead…. For those who would rather not live under the shadow of the bomb, with some hope that the human race will not destroy itself,” take down the signs, he wrote.

Despite the student protests, the signs remained posted. King and Osolin still have vivid memories of that time on campus. Civil defense was a “hot if morbid topic,” said King, who retired from the Coca-Cola Foundation in 2003 and is now director of the Pride of Kinston in Kinston, N.C. “A lot of serious-minded students and administrators gave much thought about how to save us in case the Soviets lost their minds.”

When the shelter signs first appeared on campus, many students reacted negatively to the signs’ appearance. But that overshadowed the larger issue, Osolin recalled, prompting his editorial. The signs were “symbolic of a foreign policy and an attitude in government and amongst the public (at the time) that that was a reasonable way to live, which clearly it was not,” said Osolin, a former journalist who is now a communications manager at, ironically, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory near San Francisco, once best known for its development of nuclear weapons during the Cold War.

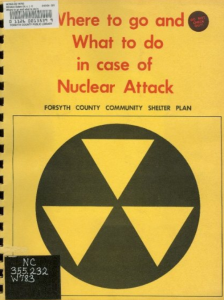

As late as 1970, the shelters were included in a Community Shelter Plan issued by the Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Civil Defense Office. Students from three nearby public schools — Speas and Sherwood Forest elementary schools and Mt. Tabor High School — were assigned to shelters on campus. The Civil Defense Office printed a special supplement in the Winston-Salem Journal warning that “millions of Americans” would die during a nuclear attack and offering this piece of advice: “never look at the flash of an explosion or the nuclear fireball.”

As late as 1970, the shelters were included in a Community Shelter Plan issued by the Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Civil Defense Office. Students from three nearby public schools — Speas and Sherwood Forest elementary schools and Mt. Tabor High School — were assigned to shelters on campus. The Civil Defense Office printed a special supplement in the Winston-Salem Journal warning that “millions of Americans” would die during a nuclear attack and offering this piece of advice: “never look at the flash of an explosion or the nuclear fireball.”

No one can recall when the shelters were “decommissioned,” although the shelter signs remained posted in campus buildings into the 1990s, long after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the cold war.

The safest place on campus during a nuclear attack may have been the basement of Tribble Hall, completed in 1963. During the building’s construction, the Department of the Navy, looking to decentralize its radio facilities in case of a nuclear attack, paid to hastily add the lowest-basement level in the “C” wing. Behind two sets of heavy steel doors, a bunker was built with its own phone hookups, utilities, water supply and special biochemical filers on the air conditioning system.

Tom Phillips (’74, MA ’78), director of the Wake Forest Scholars program, wrote about the supposedly “secret” Navy room in Wake Forest Magazine in 1994. “No Navy personnel were ever seen entering or leaving the room — just a single civilian employee who kept it in readiness for a day of doom that never came,” Phillips wrote. The bunker was converted to faculty offices in 1969.

Longtime College Registrar Grady Patterson (’24), who served on the College civil defense committee tasked with keeping students and faculty safe, also prepared to keep his own family safe. He built a fallout shelter, complete with water- and air-filtration systems, in the early 1960s underneath the patio of his home, the only such shelter on Faculty Drive. “It gave my father some peace of mind and a feeling that he had done everything he could to keep us safe,” recalled his daughter, Sarah “Sally” Patterson Barge (’57).

Cold War relics, including a radiological survey meter and a radiological dosimeter charger, collected by Ed Hendricks (courtesy New Winston Museum)

After the Pattersons moved out of the house in the 1970s, their backyard shelter was forgotten about for decades. Now-retired Professor of History Ed Hendricks bought the house in 1999 and discovered the entrance to the shelter under overgrown bushes. Down a flight of steps he found an empty supply barrel, rotting cabinets, a rusted water tank and a hand-cranked fan.

The discovery inspired him to teach a first-year seminar on “Fallout Shelters and the Cold War: Weapon, Propaganda or Survival Technique.” Students visited the bunker to understand how real the threat of nuclear war had been to an earlier generation of students. Before selling the house in 2013, Hendricks used it to store garden tools: “my version of beating swords into plowshares,” he once said.