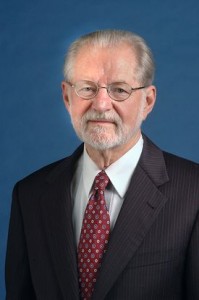

Prominent historian John Boles once described Pete Daniel (’61, MA ’62, P ’90) as a “shaper of Southern history.” Daniel is a retired senior curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and an award-winning author who has written extensively on the transformation of the South in the 1950s. He spoke at a number of events at Wake Forest in February

Prominent historian John Boles once described Pete Daniel (’61, MA ’62, P ’90) as a “shaper of Southern history.” Daniel is a retired senior curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and an award-winning author who has written extensively on the transformation of the South in the 1950s. He spoke at a number of events at Wake Forest in February

As a son of the South growing up during segregation, did your background inspire you to become a historian?

Growing up in a small North Carolina town (Spring Hope) in the 1950s, attending a segregated school, observing the contradictions in segregation, participating in sports, being active in church activities and Boy Scouts, attending movies, listening to rock ‘n’ roll, and feeling the tremors of changes along the color line created tensions that have endured throughout my life.

My curiosity about the changes in rural life that swept through the South over my grandfather’s lifetime and my own led to “Breaking the Land,” a book that covered the transformation in the rural South for the century after 1880.

The 1950s was a decade of enormous tension and transformation in the South, and as I got older I looked back with curiosity on a time mislabeled as dull and unimportant and discovered layers of unexpected and unexplored issues. “Lost Revolutions” was in one sense an exploration of my formative years but in another a challenge to the consensus take on the decade.

Books by Pete Daniel

- “Dispossession: Discrimination Against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights” (UNC Press, 2013)

- “Toxic Drift: Pesticides and Health in the Post-World War II South” (LSU Press, 2005)

- “Lost Revolutions: The South in the 1950s” (UNC Press, 2000)

- “Standing at the Crossroads: Southern Life in the Twentieth Century” (Hill and Wang, 1986)

- “Breaking the Land: The Transformation of Cotton, Tobacco, and Rice Cultures since 1880″ (University of Illinois Press, 1985)”

- “Deep’n as it Come: The 1927 Mississippi River Flood” (Oxford University Press, 1977)

As a student in the late 1950s and early 1960s can you describe the racial environment on campus at the time and how that shaped your life and your thinking?

Just before orientation in 1957, I went to a Baptist retreat and there met lasting friends — George Williamson (’61), Charles Chatham (’61) and Byron Moore (’61), to mention a few. In my home town Spring Hope there were few people who would openly discuss segregation and the implications of the Brown v. Board of Education decision, but at the retreat I discovered a freedom to discuss what had been taboo. Wake, of course, was segregated, but many students favored its (segregation) demise. As president of the freshman class, I supported integration in the student legislature. I also learned parliamentary procedure from (politics professor) Don Schoonmaker, a master, who later taught my daughter, Laura, at Wake. There were, of course, … racists in the student body, and this created lively discussions.

Freshman Class officers in 1958 (from left) Pete Daniel, president; Ann Yongue, secretary; and Larry Ward, vice president.

During these years the Montgomery Bus Boycott took place elevating Martin Luther King Jr. to national prominence, the crisis at Central High in Little Rock unfolded, and in February 1960 the Greensboro sit-ins launched South-wide sit-ins and arrests and, importantly, led to the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. I think that there were many white Southerners who wanted segregation to end, but they were reluctant to speak out for fear of being shunned. Segregationists were vocal, threatening and abusive. It was only when researching and writing “Lost Revolutions” that I discovered the complex layering of prejudice and the events that ran beneath the surface of life.

I understand that Professor of History David Smiley and Professor of History and Asian Studies Balkrishna Gokhale were major influences on you; how did they influence you?

David Smiley was a great teacher. His lectures were exciting, intellectually challenging, witty and profound. He was eccentric in his delivery and with his grimaces, and he scorned conventional wisdom. Southern students, stung by his bold claims, rushed to the library to disprove him, and he slyly smiled at their retreating backs. He claimed that education took place between the library and the coffee shop, and the human and liberal arts focus of Wake offers the opportunity for exploring ideas beyond the classroom. For me, his challenging interpretation of Southern history was refreshing, liberating. I took his seminar my first semester in the M.A. program, and the A I received is memorable to this day. Later he read the manuscript of “Breaking the Land” and made helpful suggestions. He remained my mentor.

Balkrishna Gokhale brought a new culture to Wake Forest. India had only been independent for a decade at the time, and he personified historians of India who were delving into a past that had largely been either ignored or debased by conquest. His discussion of Indian religions was objective and instructive. At one point I considered majoring in the history of India but decided that the issues in the twentieth century U.S. South were more compelling. One brash graduate student asked Dr. Gokhale if he ate steak, a meal that ran afoul of Hinduism. He calmly replied, “Only the Indian cow is sacred.”

Balkrishna Gokhale brought a new culture to Wake Forest. India had only been independent for a decade at the time, and he personified historians of India who were delving into a past that had largely been either ignored or debased by conquest. His discussion of Indian religions was objective and instructive. At one point I considered majoring in the history of India but decided that the issues in the twentieth century U.S. South were more compelling. One brash graduate student asked Dr. Gokhale if he ate steak, a meal that ran afoul of Hinduism. He calmly replied, “Only the Indian cow is sacred.”

How did your time as a foreman on the factory floor at RJ Reynolds shape your understanding of race relations?

After I completed the M.A., I hoped to teach high school, but my interview did not go well, inasmuch as the administrator all but insulted me. I left in a huff and went to work for RJR. In 1962 federal rules forced integration of the rest rooms, and I watched white workers wince as the word came down. Since I was a foreman and talked with all of the workers on my floor, I heard quite a few choice remarks. The factory manager and higher ups went ballistic when someone discovered a sheet with NAACP on it calling for a strike of the African American men who pushed trucks of cigarettes from the making to the packing room. They were paid for a lesser job, they complained. In the meeting to evaluate the problem, the factory manager suggested several draconian actions should a strike begin. I asked, “why didn’t he give them a raise?”

Since I was on the night shift, I ate dinner at a Greek restaurant with the other foremen and supervisors, and we got into some spirited conversations about integration. I learned that by sticking to my integrationist position my segregationist friends listened and argued with energy but not anger. I also learned a great deal about managing 50 workers, keeping up with the flow of tens of thousands of cigarettes, and listening to complaints as well as to good stories. Factory management did not pose the kinds of challenges that interested me, and I left in 1963 to teach at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington.

Since joining the National Museum of American History in 1981, you’ve curated exhibits on everything from New Deal photography to rock and soul music, to science in American life to a devastating flood (which led to “Deep’n as it Came: The 1927 Mississippi River Flood”). Is there any one, or two, exhibits of which you are most proud?

Since joining the National Museum of American History in 1981, you’ve curated exhibits on everything from New Deal photography to rock and soul music, to science in American life to a devastating flood (which led to “Deep’n as it Came: The 1927 Mississippi River Flood”). Is there any one, or two, exhibits of which you are most proud?

The two exhibits that stand out over my career are Science in American Life and Rock’n’ Soul: Social Crossroads. Research for the Science exhibit kindled my interest in pesticides, and the exhibit raised questions about toxicity. Researcher Louis Hutchins discovered material in the National Archives on the fire ant spray campaign of the late 1950s, and ultimately I did an article on the subject and widened my pesticide research that culminated in the Walter Lynwood Fleming Lectures at Louisiana State University and “Toxic Drift: Pesticides and Health in the Post-World War II South.” We installed an astro-turf yard in the Science exhibit that looked remarkably like a magazine advertisement from the 1950s, and there was a shed with DDT and other chemicals.

Around the corner from a house featuring a discussion of the increasing role of plastics in our culture was what I referred to as the Rachel Carson Shrine with a video that pitted her calm remarks about nature against Professor White-Stevens who denigrated her ideas. There were pro and con Carson cartoons, her books, and two pelican eggs, one healthy and the other crushed, a vivid example of how DDT weakened eggshells. The American Chemical Society sponsored the exhibit but had issues with our insistence on social history, that is, what happens when science leaves the laboratory. We were extremely fortunate that Edmund Russell, a pre-doctoral Smithsonian fellow, shared his research for what became War and Nature. Our troubled relationship with the American Chemical Society was unfortunate, but our curatorial team held to our commitment to present history and not a trade show celebrating great scientists. I was extremely proud of the exhibit.

Around the corner from a house featuring a discussion of the increasing role of plastics in our culture was what I referred to as the Rachel Carson Shrine with a video that pitted her calm remarks about nature against Professor White-Stevens who denigrated her ideas. There were pro and con Carson cartoons, her books, and two pelican eggs, one healthy and the other crushed, a vivid example of how DDT weakened eggshells. The American Chemical Society sponsored the exhibit but had issues with our insistence on social history, that is, what happens when science leaves the laboratory. We were extremely fortunate that Edmund Russell, a pre-doctoral Smithsonian fellow, shared his research for what became War and Nature. Our troubled relationship with the American Chemical Society was unfortunate, but our curatorial team held to our commitment to present history and not a trade show celebrating great scientists. I was extremely proud of the exhibit.

And the second one?

Failing to raise funds for an exhibit at the National Museum of American History, we accepted an offer from Memphis sponsors to place the Rock ‘n’ Soul exhibit there. It took a dozen years to raise funds, conduct research, collect objects, interview some hundred people connected with the music business in Memphis, and design and mount the exhibit. For me, growing up in a small town in the 1950s and listening to rock ‘n’ roll music, it was thrilling to interview such artists as Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Rufus and Carla Thomas, Billy Lee Riley, as well as Sam Phillips whose Sun Studio recorded both black and white performers, and Jim Stewart who, along with his sister, Estelle Axton, founded Stax Studio. Unlike hall of fame music exhibits, Rock ‘n’ Soul was a historical exhibit that examined the countryside with its musical heritage and then entered Memphis where it collided with the city’s powerful urban musical traditions.

Failing to raise funds for an exhibit at the National Museum of American History, we accepted an offer from Memphis sponsors to place the Rock ‘n’ Soul exhibit there. It took a dozen years to raise funds, conduct research, collect objects, interview some hundred people connected with the music business in Memphis, and design and mount the exhibit. For me, growing up in a small town in the 1950s and listening to rock ‘n’ roll music, it was thrilling to interview such artists as Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Rufus and Carla Thomas, Billy Lee Riley, as well as Sam Phillips whose Sun Studio recorded both black and white performers, and Jim Stewart who, along with his sister, Estelle Axton, founded Stax Studio. Unlike hall of fame music exhibits, Rock ‘n’ Soul was a historical exhibit that examined the countryside with its musical heritage and then entered Memphis where it collided with the city’s powerful urban musical traditions.

Three things people might not know about you: you lived in the Wake Forest trailer park as a young married graduate student; you were an aide and speechwriter for former North Carolina U.S. Senator Robert Morgan; and you’re a very fine wildlife photographer. How did your interest in photography develop?

I always smile with pride when I look back on my M.A. year when Bonnie Sullivan Daniel and I lived in the Wake trailer park and when Lisa, my older daughter was born. Laura, my younger daughter, graduated from Wake in 1980 and has had a remarkable career and is presently chief of staff for Sally Jewell, Secretary of the Interior.

In 2004 when I turned 65, I acted on a life-long dream of going to Africa, and I took along my N70 Nikon and was frankly amazed at the photo opportunities. My first major wildlife photograph came on a trip my family took to Maui during the Christmas holiday season in 2001. It was a classic humpback breach with the whale at the top of its arch and hills in the background rising in the other direction. One can take thousands of pictures of wildlife but only occasionally a photograph.

In 2004 when I turned 65, I acted on a life-long dream of going to Africa, and I took along my N70 Nikon and was frankly amazed at the photo opportunities. My first major wildlife photograph came on a trip my family took to Maui during the Christmas holiday season in 2001. It was a classic humpback breach with the whale at the top of its arch and hills in the background rising in the other direction. One can take thousands of pictures of wildlife but only occasionally a photograph.

I have upgraded my camera and lenses and each year attempt to improve on my images of leopards, lions, elephants, rhinos, cheetahs, and buffalo. These animals are beautiful and wild, and one never knows what might happen in the bush. The rangers are knowledgeable about the animals, vegetation, birds, and history. At the end of the day we pause for sundowners and watch the Southern Cross emerge and then a dense milky way emerges that resembles clouds. I’ve met guests from all over the world and shared their stories and company.

You’re going to talk to history students here about career opportunities. What’s your assessment of the field today?

The dreadful job market is a fact of life for historians. It is important, I think, to look beyond the classroom for work. I preferred working at the National Museum of American History to classroom teaching, although my academic friends suggested that I might eventually get a real job. Museum work was varied and combined collecting, exhibits and research, plus, of course, dull meetings and deadening bureaucratic duties.

The dreadful job market is a fact of life for historians. It is important, I think, to look beyond the classroom for work. I preferred working at the National Museum of American History to classroom teaching, although my academic friends suggested that I might eventually get a real job. Museum work was varied and combined collecting, exhibits and research, plus, of course, dull meetings and deadening bureaucratic duties.

Historians have skills that are valued in many jobs, especially the ability to write and analyze. Sadly, many well-educated people have not learned to express themselves well and are not able to take apart and analyze ideas. The American History museum has not hired many historians of late, but the National Museum of African American History has hired a staff and begun collecting and planning for its opening in several years. There are opportunities for historians, but increasingly one must look beyond the academy.