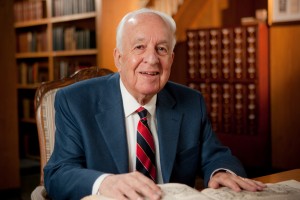

Provost Emeritus Edwin G. Wilson (’43) can still recall the fear. As a young ensign aboard a destroyer escort off the coast of Iwo Jima, he watched the bloody World War II battle for the heavily fortified Pacific island unfold.

Provost Emeritus Edwin G. Wilson (’43) can still recall the fear. As a young ensign aboard a destroyer escort off the coast of Iwo Jima, he watched the bloody World War II battle for the heavily fortified Pacific island unfold.

One incident, in particular, is still etched in his memory nearly 70 years later, he told students in a first-year writing class, “When Writing Goes to War.” He watched in horror as a Japanese Kamikaze pilot circled a nearby ship and then crashed his plane into the ship, blowing it up. “We were close enough to see what was going on: ‘the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air,’” Wilson said of watching the battle unfold on Iwo Jima in 1945.

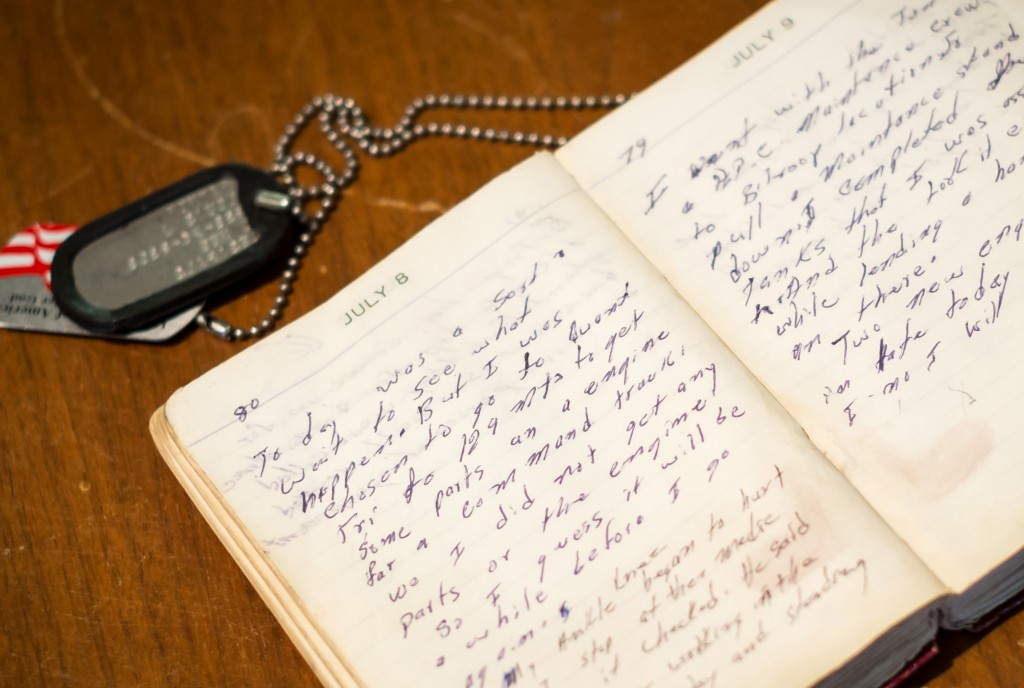

It was one of the few times that Wilson has ever publicly talked about his war experiences. Wilson, who retired in 2002, talked to students in a class taught by Visiting Associate Professor of English Sharon Raynor. Raynor’s students study letters written by soldiers who fought in the Civil War, World War I, World War II and the Vietnam War. Many of the letters are preserved in the Z. Smith Reynolds Library’s Special Collections. Veterans also visit the class to share their personal stories.

The Z. Smith Reynolds Library Special Collections houses letters from veterans. The library is seeking additional letters, particularly from alumni who are Vietnam veterans, to add to the collection. Please contact Tanya Zanish-Belcher for more details.

Germany’s invasion of Poland hit newspapers the day Wilson left his home in Leaksville (now Eden), North Carolina, for the Old Campus in 1939. “I saw the beginning of World War II that very day,” he said. “I knew that my four years at Wake Forest would be affected by the second World War. We could see day-by-day that we were on the way to war.”

About 85 Wake Forest students were killed in the war, a surprisingly large number for a small school that had fewer than 1,000 students at the time, he noted. The Wake Forest College Alumni News recorded the name, hometown and date and place of death of each alumnus in the December 1945 issue: “killed at St. Lo, France;” “killed in action, Okinawa;” “killed Philippines;” “killed in bombing mission over Germany;” “killed in North Africa;” “died in Japanese prison camp.”

The Alumni News paid tribute to the 85 alumni killed in World War II in the December 1945 issue. Click to enlarge cover.

While Wilson would go on to see action in the Pacific theatre against Japanese forces, he was more worried about Germany in the early days of the war. He traced the Nazis’ relentless march across Europe on a large map in his room and watched as classmates were drafted and left school. He was studying in his room when a friend burst in with news that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor.

Wilson’s two older brothers were already serving in the U.S. Army, one in the infantry and the other in the U.S. Army Air Forces with the 82nd Airborne Division. They saw heavy fighting, and he decided he didn’t want to be drafted into the Army. As he began his senior year, Wilson, then only 20 years old, did an “impulsive and spontaneous thing,” he told the students: He took a bus to nearby Raleigh to join the Navy.

“I had never been on a ship or even a boat,” he said. “I had never seen the ocean except at the beach in North Carolina. I wasn’t a very good swimmer. … (But) all my life I had read books about the sea. I was haunted by stories about the sea.”

His enlistment was deferred until he graduated in 1943. After completing officers’ training school at Northwestern University, he was commissioned as an ensign and assigned to a destroyer escort, a smaller ship that protected aircraft carriers from submarine attacks. As a communications officer, he was responsible for coding and decoding messages and reading — and censoring if necessary — crew members’ letters back home; he felt badly reading their letters, especially love letters, he said.

His ship made its way across the Pacific, stopping at Pearl Harbor, Guam and Saipan before arriving at Iwo Jima in the spring of 1945. He and his shipmates were fortunate, Wilson said. They never encountered any submarines, and their ship was never attacked. After supporting the invasion of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, they knew an invasion of Japan was coming next. “It’s hard to imagine what that would have been like, having gone to Iwo Jima and Okinawa,” Wilson said.

But the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought the war to an end and Wilson’s ship returned to San Diego. Wilson, then a lieutenant j.g., laughingly told the students of his short stint as captain of the USS Raymond — while it was docked in San Diego, never to sail again — after higher-ranking officers were sent home.

While in San Diego, Wilson learned that Wake Forest had accepted an offer from the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation to relocate to Winston-Salem. Soon after returning home to North Carolina, he received a call from English professor Broadus Jones inviting him to join the faculty, the start of his long association with Wake Forest as professor, dean, provost and vice president.

He told the students he hoped they had a better understanding of World War II as experienced by someone who was once their age. “As you sit there in your teens and 20s, and I stand here from long ago, to be able to perceive in someone else, not what he is now, but what he was, is very important. Because what he was, was to be like you, years ago.”

He told the students he hoped they had a better understanding of World War II as experienced by someone who was once their age. “As you sit there in your teens and 20s, and I stand here from long ago, to be able to perceive in someone else, not what he is now, but what he was, is very important. Because what he was, was to be like you, years ago.”

If you are interested in donating war letters to the Z. Smith Reynolds Library Special Collections, please contact Tanya Zanish-Belcher for more details.