(This story was originally published in 2014.)

Three alumni played important roles on the Senate Watergate Committee investigating the scandal that eventually led to President Richard M. Nixon’s resignation on Aug. 9, 1974. A fourth alumnus was on the wrong side of the Senate investigation.

Three alumni played important roles on the Senate Watergate Committee investigating the scandal that eventually led to President Richard M. Nixon’s resignation on Aug. 9, 1974. A fourth alumnus was on the wrong side of the Senate investigation.

Gene Boyce, Walker Nolan and Lacy Presnell III served as attorneys or investigators on the staff of the Watergate Committee, officially the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, in the summer of 1973. John “Jack” Caulfield, a Nixon security aide and former Wake Forest basketball player, found himself being grilled by that committee after he offered a secret clemency deal to one of the Watergate burglars.

Boyce (’54, JD ’56, P ’79, ’81, ’89) was an assistant majority counsel on the committee and the lead investigator on the team that interviewed former White House aide Alexander Butterfield. Butterfield dropped a bombshell when he revealed that there was a secret audiotaping system in the White House. Boyce, now a prominent attorney in Raleigh, North Carolina, thought the tapes would prove that Nixon wasn’t involved in the Watergate cover-up.

“My immediate reaction was ‘that clever SOB, this is going to get him off the hook, this is going to prove he’s not lying,’ ” Boyce recalled this spring. “I thought the tapes would exonerate him. Instead, it kept on building into impeachment. I don’t know what would have happened without the tapes. The truth may have come out sooner or later, but who knows?”

Walker Nolan (at left) and Gene Boyce visiting an exhibit on Watergate at the N.C. Museum of History.

Although it would be another year before the tapes were released, they proved Nixon’s downfall. Nixon fought the tapes’ release all the way to the Supreme Court before losing the case in late July 1974; he resigned two weeks later, on Aug. 9. Nolan (’65) was the committee’s expert on executive privilege and helped fight the lengthy legal battle for the tapes.

“The worst thing that could have happened was a crippled presidency, with no proof either way, and this drags on and on,” said Nolan, who later worked for Sen. John Glenn (D-Ohio) and is now in private practice in Washington, D.C. “The president would still have had a cloud over him.”

Presnell (JD ’76, P ’08) had just graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill when he joined the committee staff as an investigator. He was soon traveling to Texas and Mexico to investigate money laundering by the Nixon re-election campaign to fund the Watergate break-in and other illegal operations.

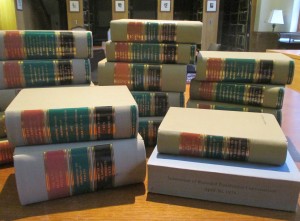

A copy of John Dean’s 245-page opening statement to the Senate Watergate Committee; donated by Walker Nolan to the Z. Smith Reynolds Library.

He still remembers White House counsel John Dean’s stunning testimony implicating Nixon in the Watergate cover-up. “I don’t know that I’ve ever witnessed anything like John Dean’s testimony,” said Presnell, who is now general counsel for the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources. “His thorough descriptions of all those conversations (with Nixon) were powerful. Put his statement and the tapes together, those were the two most crucial things.”

When Sen. Sam Ervin (D-NC) was selected to chair the Watergate hearings in 1973, he recruited a staff of attorneys and investigators, many from North Carolina, to investigate the break-in at the Democratic National Committee offices at the Watergate hotel and office building. Boyce was temporarily living in Washington to help recently elected Rep. Ike Andrews (D-NC) set up his office. He was asked to join the committee staff because of his experience as a trial lawyer, and he had a noticeable impact. The “Southern lawyer (gave) the White House several jolts,” New York Magazine once wrote about Boyce.

Presnell had worked for Ervin during summer breaks; when Ervin invited him to join the committee staff, he put his plans to attend Wake Forest law school on hold. “That was before it really blew wide-open,” Presnell recalled. “I was expecting some interesting assignments, but nothing that would have the attention of the entire country during the hearings.”

Nolan had earned his law degree from UNC and was only 30 years old, but he already had two years’ experience handling Senate hearings as counsel for Ervin’s Subcommittee on Separation of Powers. He reserved the Caucus Room in the Russell Senate Office Building for what he thought would be three weeks of hearings, not the three months the hearings lasted. “We knew it was big, but neither side (Democrats or Republicans) had any idea it would go as far as it did,” he said. “My first impression was this (the Watergate break-in) makes no sense. Nixon was running away with the election, there was no reason to do this.”

Walker Nolan has donated his personalized bound-volumes of the Watergate Committee’s final report and a copy of John Dean’s testimony to the Z. Smith Reynolds Library.

The televised hearings riveted a nation throughout the summer of ’73. Nolan, wearing fashionable checkered shirts and bow ties, could often be seen sitting behind Ervin. “It sounds like a cliché, but it’s pretty exciting to live through and participate in such an exhilarating phase of history,” Nolan told Wall Street Journal reporter Al Hunt (’65) in a story published in Wake Forest Magazine in 1973.

Boyce interviewed witnesses before they appeared before the Senate committee. The flood of information, written on 3 x 5 index cards, was so overwhelming that Boyce turned to new technology – a Library of Congress IBM computer. It was the first time a Senate committee had ever used a computer in that fashion, Boyce told a newspaper reporter in 1973.

By chance, Boyce’s team drew the interview with Butterfield. Boyce still has some of his notes from that meeting, including a sheet from a pink appointment pad with “Butterfield” written on it; the initial time of their meeting, “10 o’clock,” is crossed out, replaced with “2:15,” after Butterfield requested a delay to meet with his attorney.

Boyce had long suspected that White House conversations had been taped. After he subpoenaed records of White House meetings, the White House responded not only with dates of meetings and participants, but also summaries of what was discussed. How had those summaries been created months later?, he wondered. Investigators began asking White House aides if meetings were taped. When an attorney on Boyce’s team asked Butterfield — one of the few White House aides who knew about the system — he confirmed the existence of taping devices in several locations, including the Oval Office.

Beyond the obvious impact on the Watergate scandal, Boyce was more concerned that the tapes could lead to an international crisis. When Butterfield mentioned that the taping system included Aspen Cabin at Camp David, Boyce immediately remembered that Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev had stayed there only weeks earlier during a summit with Nixon. “Oh my God, we’ve secretly tape recorded Brezhnev,” Boyce remembers thinking. (There was never any evidence that foreign leaders were taped at Camp David.)

Presnell was in the committee room when Butterfield testified before the full committee several days later. “The caucus room was filled,” he recalled. “Clearly everyone who was present knew that was a pivotal moment. No one knew exactly how it would unfold, but the fact that there were tapes of these critical moments, that should tell the complete story.”

New York City police officer Jack Caulfield provided security for Richard Nixon during the 1968 Presidential campaign and later became a White House security aide.

Overshadowed by the explosive testimony of Butterfield and Dean, and prominent figures such as John Ehrlichman, Bob Haldeman and Gordon Libby, was Jack Caulfield, who was one of the first witnesses to testify before the committee. Caulfield had a compelling back story and a spy-novel worthy turn as a messenger in the post-Watergate cover-up.

A native of the Bronx, Caulfield attended Wake Forest for two years in the late-1940s on a partial basketball scholarship before dropping out because of financial problems. In his 2008 autobiography, “Caulfield, Shield #911-NYPD,” he writes that he fell out of favor with basketball coach Murray Greason when Greason caught him smoking after practice one day. Caulfied returned to New York and served in the U.S. Army before joining the NYPD. He became a decorated detective and once arrested a group of French-Canadians who were plotting to destroy the Statue of Liberty and the Washington Monument.

Caulfield was chief of security for Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign. After Nixon was elected, Caulfield was appointed White House liaison with federal law enforcement agencies. But he also undertook covert political operations including wiretaps and tax audits against unfriendly reporters and Nixon’s political opponents. The New York Times once described him as “performing dirty tricks for the White House well before it assembled the ‘plumbers,’ as the perpetrators of the Watergate break-in were known.”

In his autobiography, Caulfield wrote that he proposed a secret operation, dubbed Operation Sandwedge, to increase intelligence-gathering and electronic surveillance against Democrats during the 1972 presidential race. But he dismissed the idea of breaking into DNC headquarters as “too dangerous.” Some historians have called Sandwedge an early model for Watergate.

John Dean told the Watergate committee that Attorney General John Mitchell and presidential assistant John Ehrlichman rejected Caulfield’s plan; an alternate plan developed by other administration officials eventually led to Watergate. In his famous “cancer on the presidency” conversation with Nixon, captured on the Watergate tapes, Dean tells Nixon that rejecting Caulfield’s plan “might have been a bad call … he is an incredibly cautious person and he wouldn’t have put the situation where it is today.”

Caulfield agreed, writing in his autobiography, “Had there been Sandwedge, there would have been no Liddy, no Hunt, no McCord, no Cubans, and, critically . . . no WATERGATE.”

Caulfield had already left the White House before the Watergate break-in to become assistant director of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. According to Caulfield’s testimony at the Watergate hearings, several months after the break-in Dean asked him to deliver messages to convicted Watergate burglar James W. McCord Jr., who was a friend of Caulfield’s.

In a series of clandestine meetings, Caulfield passed on to McCord offers of money and executive clemency from the “highest levels of the White House” if he didn’t testify against administration officials; McCord refused. Caulfield was never charged with any Watergate-related crimes. He died in 2012.