Angelou first came to Wake Forest in 1973 when she spoke (and sang) to a standing-room only crowd in DeTamble Auditorium during the University’s first Black Awareness Week. The reaction of students, black and white, left her “dumbfounded,” she later wrote in Ebony magazine. “I had pulled no punches, and softened no points, yet Whites stood beside Blacks, clapping their hands and smiling. … I knew that morning, that one day I would return to The South in general, and North Carolina in particular.”

She returned to Wake Forest four years later to receive an honorary degree and again in 1982, when she was named the first Reynolds Professor of American Studies. In 2002, the School of Medicine created the Maya Angelou Center for Health Equity to address racial and ethnic disparities in health care and outcomes.

Following her death at the age of 86 on May 28, 2014, Wake Forest President Nathan Hatch rightly called her “a towering figure at Wake Forest and in American culture.”

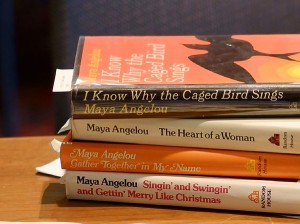

She worked with Martin Luther King Jr., married a South African freedom fighter, appeared on stage and in films, and bared her soul and inspired us in more than 30 books of fiction and poetry, including “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” and “Just Give me a Cool Drink of Water ‘Fore I Die,” nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

She worked with Martin Luther King Jr., married a South African freedom fighter, appeared on stage and in films, and bared her soul and inspired us in more than 30 books of fiction and poetry, including “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” and “Just Give me a Cool Drink of Water ‘Fore I Die,” nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

She received the National Medal of Arts in 2000 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2010. She delivered the poem “On the Pulse of Morning” at Bill Clinton’s first inauguration in 1993. At her memorial service in Wait Chapel, a host of dignitaries, including Clinton, Oprah Winfrey and First Lady Michelle Obama spoke of her legacy.

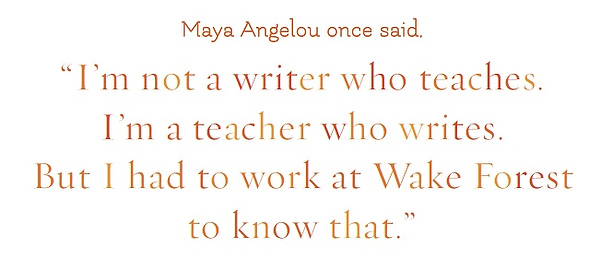

Yet, for all her acclaim around the world as a poet, author, actress and civil rights icon, she always returned home to Winston-Salem and to teach at Wake Forest. Said Provost Emeritus Edwin G. Wilson (’43) at her memorial service: “We cherish the remarkable story of an enormously gifted woman who would have been welcome anywhere in the land, but who chose — I think because somehow she knew that besides honoring her, we would love her, and we wanted her as a companion — she chose — against all normal expectations — she chose to come to this Southern University and make it her home.”

In the essays that follow, Wilson celebrates the “private Maya Angelou” who welcomed students into her home; Former Dean of the College Tom Mullen (P ’85, ’88) remembers the first time that Angelou mesmerized students and his “woefully far-fetched” invitation to her to return to teach at Wake Forest; Mutter Evans (’75) looks back on that magical night in 1973; and a host of students honor Maya Angelou the teacher.

— Kerry M. King (’85)

For more reflections on Maya Angelou or to view her memorial service, visit mayaangelou.wfu.edu

I suspect that fate, or God, had a hand in bringing Maya Angelou to Wake Forest in 1973. If so that hand found willing helpers in the Wake Forest College Union’s committee on Black Awareness Week and the leaders of Wake Forest’s Afro-American Society. If what I’ve been told is correct, a small number of African-American students took the lead in proposing the invitation, with the strong support of several white students. These students, of both races and predominantly female, were well aware of the racial uneasiness — perhaps tension would not be too strong a word — on campus then. Evidently they hoped having Miss Angelou speak would help ease tensions, or at least open the way for straightforward discussion. Seldom can a committee’s work have produced such successful long-term results.

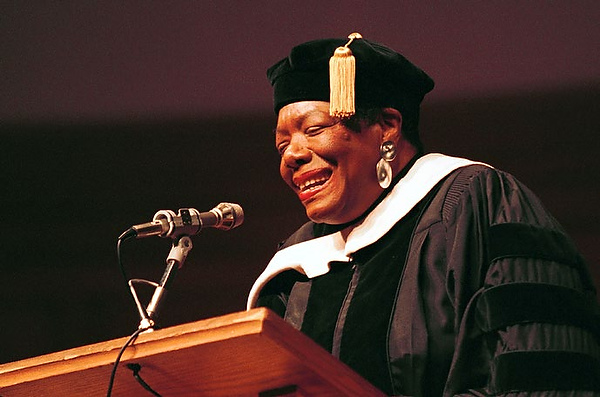

Miss Angelou (the first of her numerous honorary doctorates came two years later) on that first visit spoke in DeTamble Auditorium in Tribble Hall. DeTamble was not nearly large enough for the audience, even though Maya Angelou’s fame was nothing like what it later became. All seats were filled; people sat on steps and spectators filled the standing space to the back wall and out into two hallways. It’s not surprising that when Dr. Angelou referred years later to this first encounter with Wake Forest, she thought she had spoken in Wait Chapel, as she did many times over subsequent years.

Miss Angelou (the first of her numerous honorary doctorates came two years later) on that first visit spoke in DeTamble Auditorium in Tribble Hall. DeTamble was not nearly large enough for the audience, even though Maya Angelou’s fame was nothing like what it later became. All seats were filled; people sat on steps and spectators filled the standing space to the back wall and out into two hallways. It’s not surprising that when Dr. Angelou referred years later to this first encounter with Wake Forest, she thought she had spoken in Wait Chapel, as she did many times over subsequent years.

Maya Angelou swayed and danced, bounced and pranced across the tiny stage. Though her scheduled topic was “The Significance of Black Literature in America,” she decided it did not reach far enough into what really mattered to her and to the students of that civil rights era. Along with reading from the poems of James Weldon Johnson and other African-American poets, including herself, she devoted much of her presentation to what it had meant to grow up in the South as a human being with black skin, and what African-Americans, including students, still had to endure. She said many things that were hard for white people to hear, but she interspersed these with song and dance and humorous anecdotes. And she repeatedly emphasized those qualities that make us all human. The audience, with me included, was enthralled, even mesmerized. When she finally concluded to a standing ovation — a genuine one, not the kind prompted by sitting too long — all were invited to a reception outside DeTamble.

Soon a number of students asked her whether she would be willing to move with them to a more comfortable place to continue the questions and answers, to a lobby outside the Magnolia Room. Most if not all the students sat on the carpet, literally at the feet of Miss Angelou and Miss Dolly McPherson, a scholar accompanying her. Some older faculty types, like Elizabeth Phillips, Eva Rodtwitt and me, stood against one of the walls, unwilling to miss what Maya Angelou would do. Black students described what they saw as their mistreatment and disadvantages on what they perceived to be a “white” campus. White students defended their behavior and called attention to what they saw as the over-sensitiveness of the black students. Aware that they were really talking to each other rather than to her, she urged them (possibly “commanded” them) to speak not to her but to each other and proceeded to lead a kind of town hall meeting. This went on for three hours, ending after midnight, to another standing ovation full of energy and emotion.

We witnessed an astonishing demonstration of teaching effectiveness on as touchy a subject as one could have imagined that wondrous evening. As the students gradually disappeared, I made my way to Miss Angelou, thanked and congratulated her on what she had done, both in DeTamble and in Reynolda Hall, identified myself as dean of the college and offered the suggestion that, should she ever decide to slow down her constant traveling and settle down in one place, she might be well advised to think about making that place a college campus. Should she reach that point, I said, I hoped she might think of Wake Forest as a possible stopping place. That she would ever take such an idea seriously seemed to me at the time woefully far-fetched. Making it less so were Drs. Phillips and Rodtwitt, who asked Maya Angelou and Dolly McPherson to their home for something to drink after that long evening. The two visitors quickly accepted, and the four women talked far into the morning. A couple of years later, thanks especially to Dr. Phillips, Provost Ed Wilson (’43) and other members of the English Department, Miss McPherson joined our English faculty, giving Maya Angelou yet another reason to think of settling in Winston-Salem and becoming the Reynolds Professor of American Studies at Wake Forest. Fate, or God, had truly worked a wonder.

Tom Mullen (P ’85, ’88) was a history professor from 1957 to 2000 and dean of the college from 1968 to 1995. He was named an honorary alumnus in 1995.

There was great anticipation and a great turnout that evening. We were outside the Magnolia Room. We sat on the floor. We sat on the chairs. We leaned up against the wall, and we just sort of sat at her feet as she held camp. We talked about some of everything under the sun and the issues. She was so engaging. I remember Dr. (Tom) Mullen … said to me and a few other students, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice to have someone like that on our campus?’ and I said, ‘Absolutely, yes!’ … When we left we were all revived and hopeful. During that time period, of course, there were no black faculty members … and the black student population was very, very small. It was so encouraging to us to have someone speak and express herself. Quite frankly that night was the beginning of my friendship with her. …

I like to remind people that’s what makes Wake Forest University so unique. It is a liberal arts University. There’s never been one opinion. There’s been a diversity of opinions. Another thing that made students in the late ’60s and ’70s so proud was to know that Dr. (Martin Luther) King had actually been invited to speak at Wake Forest before we were even there, in the early ’60s. Her (Angelou’s) introduction to Winston-Salem and Wake Forest began as a result of a lecture one night, and the warmth that she received and the dialogue and the conversation that began fostered a major discussion that allowed her to join the faculty. I think it says a lot about the administration — President James Ralph Scales, Dr. Mullen and others in the administration who recognized the wealth and breadth of experiences that she could add to teaching, and it was not minimized because of a lack of a doctoral degree. Her coming and being added to the faculty is something we had a great deal of pride in.

I like to remind people that’s what makes Wake Forest University so unique. It is a liberal arts University. There’s never been one opinion. There’s been a diversity of opinions. Another thing that made students in the late ’60s and ’70s so proud was to know that Dr. (Martin Luther) King had actually been invited to speak at Wake Forest before we were even there, in the early ’60s. Her (Angelou’s) introduction to Winston-Salem and Wake Forest began as a result of a lecture one night, and the warmth that she received and the dialogue and the conversation that began fostered a major discussion that allowed her to join the faculty. I think it says a lot about the administration — President James Ralph Scales, Dr. Mullen and others in the administration who recognized the wealth and breadth of experiences that she could add to teaching, and it was not minimized because of a lack of a doctoral degree. Her coming and being added to the faculty is something we had a great deal of pride in.

Maya Angelou was, from the beginning of her Wake Forest career, already a public figure: visible onstage, on television, in books, wherever listeners or readers gathered to hear her stories and her poems of suffering and hope. She warned us, she challenged us, most of all she inspired us. It would be almost impossible to think of another “celebrity” of our time who maintained, through so many years, the power to capture and hold an audience, whatever the nature of the audience. On her best days, she was, indeed, triumphant.

And yet, when I look back at Maya Angelou’s 32 years on the Wake Forest faculty, I think first of occasions when there was no audience as such, when she was not “onstage,” when she was inexpressibly direct and honest and conversational. Twice I attended one of her classes in Brendle Recital Hall. The students had been told that, at the end of the term, they would have to “perform,” most likely by reciting a poem or a scene from a play. She then asked one student to read Shakespeare’s 29th sonnet: “When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,” (Maya had once said of Shakespeare that he was her “first white love.”) She then spoke of Paul Laurence Dunbar, a black American poet whom most of the students, I think, were learning about for the first time. Then, in a bow to one of her favorite poets, the Scotsman Robert Burns (whose cottage home she had once visited), she recited those hopefully prophetic last lines of one of Burns’ best-known poems:

For a’ that, an’ a’ that,

It’s coming yet, for a’ that.

That man to man, the world o’er,

Shall brothers be, for a’ that.

More frequently, I saw Maya at her home: a veritable museum of books, paintings, sculptures, mementos of a collector’s life. Sometimes I was there to celebrate a holiday: Christmas, in particular, was a time for everyone to put decorations on the tree. Sometimes I had an opportunity to meet a well-known visitor from out of town: James Baldwin, Odetta, Sterling Brown, Jessica Mitford, Oprah Winfrey. (One never knew who might be present.) Sometimes I brought with me, with Maya’s permission, a visitor who wanted to meet her (she received graciously every such guest): a young woman from Texas who was writing a book about men and women who had conquered adversity; a committee of educators who hoped that she might speak at their national convention; a high school basketball player considering an offer from Wake Forest (his parents had told him how much they admired Maya Angelou).

One occasion in Maya’s home remains central to my memories of the “private” Maya Angelou. Twenty-some members of the Wake Forest College Democrats, planning to go to the Democratic Convention in Charlotte in 2012, wanted to meet her. She readily agreed, and a few days later we were seated at a long table in her dining room, drinking iced tea (prepared from her own recipe), and listening not to partisan or even politically motivated words but, rather, to her insights into what can be accomplished by young people with courage, conviction and hope. She then asked the students, one by one, to introduce themselves and talk for a few minutes about their background and their plans for the future. A few weeks later, after the convention, Maya called me and asked me to invite the students to return to her home and tell her about their experiences at the convention. We did go back, and again each student spoke, and Maya carefully listened.

The last time I saw Maya, a week or two before she died, she was, as usual, seated in a high-backed chair, papers and books and a crossword puzzle on the table in front of her, still alert to every nuance in our conversation. She offered me a glass of iced tea, we spoke about her new book on Nelson Mandela, and she said she was looking forward to teaching in the fall. I knew that she was physically weak, but I saw that, mentally and spiritually, she was still the same Maya Angelou that I had known and admired for almost 40 years.

I thank Maya Angelou and bless her for her gifts to me and to our University.

Edwin G. Wilson (’43) is provost and professor emeritus. His latest book is “The History of Wake Forest University, Volume V, 1967-1983.”

In class, Dr. Angelou made us learn each other’s names. She wanted us to understand how you feel when someone calls your name across the room. She wanted us to experience what it meant to have your chest swell with pride because someone remembered your name.”

— Nicole Little (’13)

There were countless moments that I will cherish, but the theme of the course, ‘I am a human being, nothing human will be alien to me’ is something I carry with me daily.”

— Matt Williams (’09, MA ’14)

The memory of being a student in Dr. Angelou’s class at Wake Forest will forever be etched in both my heart and my mind. She taught me more than I can ever describe and her presence left an indelible mark that will thankfully stay with me for the rest of my life. The way she carried herself and the lessons she shared molded and shaped me into a better person, a stronger student and a louder voice.

— Dawn Calhoun (’99, MA ’07)

Corny as it sounds (I’m just gonna say it), I felt the air change when Maya Angelou entered the room. Her presence. Electric. Confusing. Exciting. Wondrous. She was a phenomenal woman (before I had even heard of, much less read the poem); I needed no one to tell me she was a force, a bigger-than-life soul. The energy of Maya was just there, here, there. She spoke of her writing process; her habit of wearing only a large caftan with nothing else underneath which might inhibit or stifle her writing, the only other item on her body being a hat, with which to hold her thoughts in her head until she could put pen to paper: ‘I cannot let my thoughts escape.’ She smiled fiercely, broadly, raising her eyebrows and eyeing us individually. It was the first time that I really understood the phrase ‘thoughts are things.’

Corny as it sounds (I’m just gonna say it), I felt the air change when Maya Angelou entered the room. Her presence. Electric. Confusing. Exciting. Wondrous. She was a phenomenal woman (before I had even heard of, much less read the poem); I needed no one to tell me she was a force, a bigger-than-life soul. The energy of Maya was just there, here, there. She spoke of her writing process; her habit of wearing only a large caftan with nothing else underneath which might inhibit or stifle her writing, the only other item on her body being a hat, with which to hold her thoughts in her head until she could put pen to paper: ‘I cannot let my thoughts escape.’ She smiled fiercely, broadly, raising her eyebrows and eyeing us individually. It was the first time that I really understood the phrase ‘thoughts are things.’

— Lundi Ramsey Denfeld (’84)

I attended class full-time and worked full time as an undergraduate. Needless to say, I had a turbulent undergraduate experience. Meeting you during my undergraduate tenure gave me the strength to stay the course. Thank you for your shining example, your caring way and sharing your immense mental strength with me and countless others.

— Charles Elam Gibson III (’09)

The first moment of the first day of class she asked everyone to state their names and told us that, from that day forward, she would remember them. She then shared with us a smorgasbord of mind-opening experiences, from slave narrative readings to in-class debates on difficult issues to dinner at her house with her friend Alex Haley. Many years later I saw her in Durham at a dance performance and approached her with my wife to say hello. True to her word, she remembered me and exclaimed, “HELLO, YOUNG MR. STEVENS,” in her booming baritone voice, much to my wife’s delight. She will be greatly missed.

— Eric Stevens (’87)

SHE, Dr. Angelou, THE phenomenal woman drew ME to Wake Forest University. For two years she freely and lovingly deposited wisdom within me & countless WFU students. She hosted us in her home and always punctuated the affair with food for the soul and the belly! One semester, she gifted each of us a leather briefcase with our full name etched in gold script. I remember her saying, “I want you to go into the world feeling like somebody, I want you to go into the world with your heads high, but your hearts higher. Remember, you have a name.

— Tycely Williams (’97)

I met Maya in the early ’70s. DeTamble was packed. As one of the few African-American students, I knew the campus was in for a treat and she delivered. Afterward, she was like the Pied Piper, mesmerizing everyone who sat and stood at her feet. Thank you, Maya, for your energy, passion, love of education and all students. Rest In Peace, Maya. Well Done!

— Clement Brown (’73)

THANK YOU, Dr. Angelou! For teaching me over my stubborn resistance what a valuable motivation that fear can be; for showing me the living example of exhibiting great class and dignity no matter the hardship(s) that may be thrust in one’s way; & reminding me how valuable my mother’s advice can be. It was her recommendation that led me to your class. I am forever richer, and grateful, for having known you both. Mom, you & Wake Forest, “Mother so dear” indeed!

— The Hon. Michael G. Takac (’84)

Dr. Angelou spoke at the Final Four banquet for field hockey when Wake Forest hosted the event. In a room full of female college athletes she commanded attention with her soft, powerful voice. She asked each of us to be our greatest selves and not be afraid to shine — have the courage to be yourself, always and always better yourself. She was beautiful. To hear her speak was beautiful — an ease of performance that her literature tells us took her years to learn. May she rest in peace and may her words continue to teach, encourage and inspire.

— Lauren Crandall (’07)

Dr. Angelou was a terrific teacher — about literature, about writing, about life. I was honored to be a student in her class.

— Jamie Weinbaum (’98)