on’t gasp when you hear that Ted Gellar-Goad teaches naked. The young Latin scholar is always appropriately clothed in suit and tie. It’s his teaching style that bares all in a classroom stripped of laptops and other electronic devices, leaving students and teacher exposed to face-to-face learning.

on’t gasp when you hear that Ted Gellar-Goad teaches naked. The young Latin scholar is always appropriately clothed in suit and tie. It’s his teaching style that bares all in a classroom stripped of laptops and other electronic devices, leaving students and teacher exposed to face-to-face learning.

Videos? No. Skits based on Roman plays featuring basketball star Chris Paul (’07) and his State Farm ad alter ego, Cliff, as lead characters? Yes. PowerPoint presentations? No. Mythological role-playing games? Yes — in fact the teacher developed his own. In an era when technology has changed the teacher’s role, this professor’s creative approach to motivating millennials has changed technology’s role — and succeeded in making the past relevant to their present.

Outside the classroom, 30-year-old Theodore Harry McMillan Gellar-Goad is as plugged in as anyone of his generation. He’s got a Smartphone, a website and a Twitter account. He composes computer music. But when it comes to class time, immersion in Latin language and literature focuses on discussion, practice, review and reflection. Anything requiring “information transfer” is managed outside the classroom walls.

The assistant professor of classical languages and faculty rising star exudes intelligence, curiosity and creativity and is distinguished by trendy eyeglasses, multiple piercings and witty repartee with students. He might be mistaken for a student himself — if not for that suit and tie and a friendly-yet-authoritative demeanor in the classroom. Then there’s the fact that he wrote his doctoral dissertation on the Roman poet Lucretius.

“I love Latin and always loved reading Latin because it was like a puzzle or math problem I could work through that made sense and had chunks that fit together,” says Gellar-Goad. “One of the things I value most about Greek and Roman art and culture and literature is that as we interrogate these subjects, they interrogate us. The study of literature, art and architecture makes us re-evaluate our own perceptions. The challenge is to get students to see the value in that.”

One gets a sense of that value by spending time in his office. Late in the spring semester, his post in the bowels of Tribble Hall is filled with papers, books and boxes as he prepares to move upstairs. The aura of ancients like Catullus, Plautus and Menander fills the air. Evidence of his students’ creative engagement is everywhere: an “Animal House”-themed poster on grammar’s dative case decorates one wall; a mobile dangles from the ceiling; a handmade vase retelling part of the epic poem “The Argonautica” by Apollonius Rhodius, painted in a hybrid of comic book and Greek script, occupies a table. On the desk lies sheet music — his own work in progress for string quartet — in which rhythm and direction of pitch are determined by his favorite Greek poem.

Born in Kansas City, Kansas, Gellar-Goad grew up in Charlotte, the fifth of five children, and declares himself a North Carolina boy at heart. Surrounded by music from birth — his psychiatrist father played classical recordings to soothe him in the crib — he started playing violin at 2, took up piano at 10 and the French horn in his teens. He began writing music in sixth grade, contemplating a career as a professional composer. At the age of 16 he applied to colleges and eventually enrolled at N.C. State University in Raleigh, staying close to home because his mother threatened to move with him if he ventured out of state.

It was there he discovered his passion for Latin, which he was inspired to learn because he enjoyed requiem masses of Mozart and Verdi and wanted to read them in their original language. After graduating summa cum laude with two bachelor’s degrees and three minors, he moved on to UNC-Chapel Hill where he earned a master’s in ancient Greek and a doctorate in classics, eventually choosing classics as a career and music composition as a release rather than an obligation. A fan of Wagner, Tolkien and H.P. Lovecraft, he came to Wake Forest in 2012 as a teacher-scholar postdoctoral fellow specializing in Republican and Augustan poetry — particularly comedy, satire, Lucretius and elegy.

Motivating students who may not share his level of enthusiasm for Latin served up a reality check for Gellar-Goad, who believed that teaching the way he had been taught was not the best way to make his subject engaging. He took advantage of resources in Wake Forest’s Teaching and Learning Center and discovered José Antonio Bowen’s book, “Teaching Naked,” which advocates removing technology from the classroom to improve student learning. The concept resonated with Gellar-Goad’s “think outside the box” mindset and revolutionized his teaching.

He wondered how he could reinvent a Latin grammar prose and composition course in a way that would inspire students to do the work, give them the confidence to succeed, provide a supportive environment and affirm the content’s value. A creative challenge required creative thinking, and Gellar-Goad came up with an idea: using the pedagogical principles of gamification, he wrote and designed a tabletop role-playing game loosely modeled on “Dungeons and Dragons.”

he basic idea was to create a superstructure of fun on top of this really difficult subject that intrinsically links the value of the game with the value of learning the language,” he says. “I knew going into planning that Latin prose composition is a hard, hard course and textbooks are outdated and very remote from modern American experience. The textbook I use, which is the gold standard in the field, was last revised to a major extent in 1936. Students don’t want to translate sentences about British colonial ventures in India or what it’s like to be a member of the male aristocracy in London.”

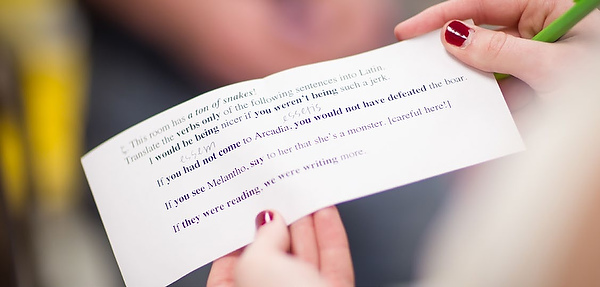

In the game, “Challenge of the Sphinx,” each student adopts the fictional persona of a hero/heroine found in Graeco-Roman mythology, developing the character’s backstory, personality and game strategy — all in correct Latin grammar and sentence structure — as their heroes are challenged by mysteries, monsters and other obstacles. As players successfully complete assignments like scribe spell-scrolls, side quests and dungeon maps, they get closer to defeating the Sphinx, a monster of riddles. “The monster wants them to have less control over their language because that would make them less likely to solve the riddles and defeat the Sphinx,” says Gellar-Goad. “As the students get more skilled at Latin grammar their characters become more ready to fight the Sphinx.”

The quest culminates with a final battle that incorporates all the skills and tools they have used over the semester into team and individual exercises. During the game students gain experience points through assignments, homework and projects that can improve their course grade. In-class meetings are “flipped” classrooms with Q&A sessions and exercises that allow students to apply material they prepared before class.

For Gellar-Goad it was demanding to create the game but rewarding to see students work hard without feeling overwhelmed. He used a role-playing structure to give students opportunities to learn from their mistakes in a way that they weren’t personally at stake — their sense of self-worth or their skills in Latin weren’t the thing at risk. “What was at risk was does their character beat the monster or get beaten by the monster? Do they get to buy all the things they want to buy for their character in the marketplace? Having an intermediary between their own self and the subject matter by having this fictional persona allowed them to take greater risks than they’re accustomed to.”

Senior Lee Quinn, who participated in the game, says Gellar-Goad teaches students to develop a personal connection to the information, describing the class as “an experiment in 21st century pedagogy; a synthesis between technology and ancient works that makes students capable of grasping the most poignant and powerful messages of what would be highly exclusive materials.”

Former student Emily Madalena (’14), whose English honors thesis was 31 pages long, points out that she took 77 pages of single-spaced notes in Gellar-Goad’s class on Greek and Roman comedy. She describes him as not only a great teacher but also a kind man, and she finds his passion contagious. “Many themes in the plays that we examined are problems that we, in our own 21st century, struggle with — familial tension, rape culture, identity and so on,” says Madalena, who is pursuing her master’s degree at University College London. “His class showed me that we can learn from the past and apply old lessons to our ‘new’ lifestyle. Furthermore, by reading ancient plays and laughing hysterically at them, I learned that if I can relate to people from thousands of years ago, I can certainly strive to relate to people across cultures and generations.”

A semester with Gellar-Goad brought Chris Morin (’14) out of his comfort zone by requiring students to adapt and perform a play in front of a live audience. “It was an invaluable experience I wouldn’t trade for anything,” he says. And senior Mary Somerville, who hopes to someday teach Latin, says Gellar-Goad asks much of his students but they enjoy the work because his classes are engaging and useful. “He has a knack for adjusting to student interests without abandoning his lesson plans,” she says.

So, grammar and games aside, why Latin? Gellar-Goad is ready with a confident answer: for virtue, for profit and for fun.

For virtue? Latin is hard, says the professor; studying and learning Latin creates a sense of grit and determination — a mindset and work ethic that will serve students well into whatever field they go, be it teaching, research, public policy or human relations. “Unlike English where meaning is based on word order, Latin is based on word endings and requires a greater degree of analysis and critical assessment skills to get through a Latin sentence,” says Gellar-Goad. “Analysis and critical thinking are two core elements of a successful career and a fulfilling life in the modern world. Because it’s high literature the language is artfully constructed; that pushes people to think creatively. To think about how the art of language can reflect and represent and even structure reality, to find beauty in the verse or line, allows us to find beauty in the outside world.”

For profit? “Studying Latin and Greek give you the sorts of things you need to succeed in the modern world: a huge vocabulary, an ability to pick sentences apart and figure out what they really mean, plus an ability to cut through the BS and the propaganda because you can see how language is used insidiously or manipulatively.”

For fun? “Some of the best things ever written in any language in any time have been written in Latin. And a number of people I know would have liked to have known Latin before they got their tattoos.”

Gellar-Goad recounts the story of classics faculty colleague Michael Sloan, who asks students to raise their hands if the answer is “yes” to each of three questions: “Do you want to go to grad school?” “Do you want to get a job?” “Do you want to be a better person?” When those three questions are answered, if your hand is raised you should take Latin or Greek because studying these cultures makes you a better citizen of the world and a better contributor to the world.

There’s a whimsical poster in Gellar-Goad’s office that’s a product of his own creative mind. It depicts legendary tough guy Mr. T, clad in chunky gold chains and a ‘toga,’ thrusting his best “A-Team” forefinger at the viewer. The caption, in Greek, could be the professor’s ultimate lesson: “I pity the fool who has never read Aristophanes.”

It is possible to connect the past to the present, making it relevant — and fun. Indeed, at Wake Forest, it has been done.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………

Curiosity matched by creativity

Last spring Wake Forest’s Teaching and Learning Center honored Ted Gellar-Goad with an Innovative Teaching Award to recognize the redesign and implementation of his Latin Advanced Grammar Prose and Composition course into a semester-long mythological role-playing game.

Last spring Wake Forest’s Teaching and Learning Center honored Ted Gellar-Goad with an Innovative Teaching Award to recognize the redesign and implementation of his Latin Advanced Grammar Prose and Composition course into a semester-long mythological role-playing game.

“Ted Gellar-Goad came to the TLC as soon as he arrived, immediately joining the New Faculty Learning Community and attending TLC workshops as well,” said Director Catherine Ross. “His curiosity was matched by his creativity in thinking of new ways to apply the learning research to his courses in Latin, and he was always excited by the challenge of motivating his students. This transformation of one of the most difficult and yet important courses in the Latin curriculum was a huge challenge, but with Dr. Gellar-Goad’s grounding in the research on learning, and his immense energy and creativity, he succeeded in engaging his students in an amazing learning opportunity.”

……………………………………………………………………………………………………

One semester, two perspectives

“One of my favorite lessons that I continue to share with my friends and family is regarding characteristics of Greek and Roman writers and citizens. During one class Dr. Gellar-Goad featured pictures of Greek and Roman high-status women. He asked the class what they thought of the women. My classmates immediately assumed they were slaves or actors wearing masks because the women had a darker skin tone and tightly coiled hair. I was shocked by some of the responses that I heard, but Dr. Gellar-Goad reassured the class that the portraits actually reflected those of high-status. Being that I was the only African American in my class this lesson was very valuable, and I immediately felt a sense of pride. It taught me and classmates to not believe (current and past) stereotypes regarding education, success, race or sexuality.”

– Abriana Kimbrough, senior, of Winston-Salem, communication major/psychology minor

“By being pushed to find new avenues of making classics relevant to students I’m doing them a service, and they’re doing a service for themselves by actually listening and engaging with me. In spring semester we talked about representation of race and ethnicity in ancient world; something most Americans seem to think about Greeks and Romans is that they were white, and they were not. A student said she changed the way she thought about it. Having these kinds of discussions can be a way to talk about how issues of race and gender are socially constructed. Talking about this in a remote context like ancient Greece and Rome is a way to talk about ourselves without risking too much — sort of in parallel with creating a fictional character whom you use to get through Latin prose composition.”

– Professor Ted Gellar-Goad