With little fanfare, Andy Heck (’70, P ’98) takes the two aging rolls of butcher paper out of a plastic grocery bag and begins unrolling them on the kitchen countertop at his home in Pawleys Island, South Carolina.

“The scroll,” as he calls the two rolls of paper, is the bridge between those different parts of his youth, a get-well message of more than 100 feet sent to him by Wake Forest after he was seriously wounded in Vietnam in 1968. If the onetime Deacon football star unfurled the scroll end-to-end on a football field, the paper would stretch from the end zone to the 35-yard line.

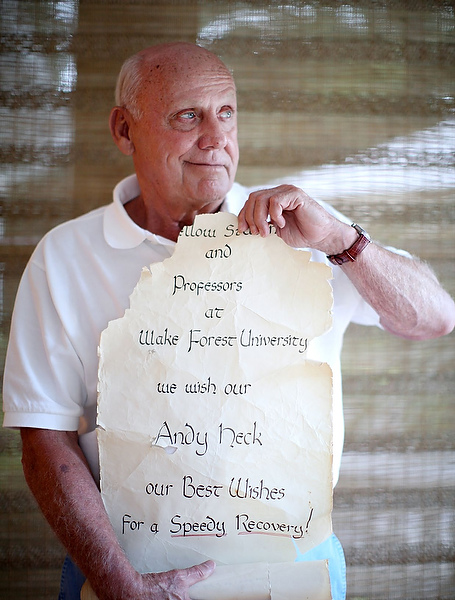

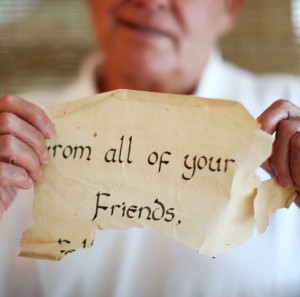

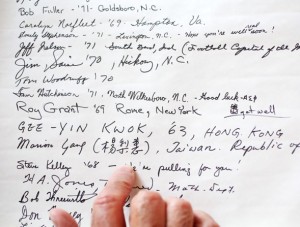

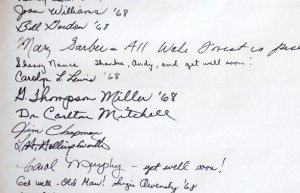

As he unrolls the scroll, hundreds of signatures of friends, classmates and professors appear. The top of the scroll is torn and tattered, but the heartfelt messages remain as clear and poignant as the day they were written: “From all of your Friends, Fellow Students and Professors at Wake Forest University we wish our Andy Heck our Best Wishes for a Speedy Recovery!” The sentiments helped him recover from the physical and emotional wounds of Vietnam, allowing him to go on to a rich family life and high-flying business career.

As he unrolls the scroll, hundreds of signatures of friends, classmates and professors appear. The top of the scroll is torn and tattered, but the heartfelt messages remain as clear and poignant as the day they were written: “From all of your Friends, Fellow Students and Professors at Wake Forest University we wish our Andy Heck our Best Wishes for a Speedy Recovery!” The sentiments helped him recover from the physical and emotional wounds of Vietnam, allowing him to go on to a rich family life and high-flying business career.

For the last 46 years, Heck has kept the scroll largely locked away with his memories of the war, first in a box under his childhood bed, and then in his garage, where it survived a fire that destroyed his home. Try as he might, it was impossible for him to separate the scroll from his service in Vietnam. After all, he received it only because he was grievously wounded — twice within six months. Heck earned two Purple Hearts in Vietnam and still bears the scars from shrapnel that pierced his legs, arms and back.

“There were times I’d take a look at it, and I’d start thinking about things and I’d put it aside,” Heck says. “I wasn’t ready to deal with a lot of it, all the things that made me remember places and people.”

![]() t’s only been in the last few years that he’s reconciled with the scroll, choosing to remember the goodness of Wake Forest people more than the war and pain and loss of that time in his life. Though he does not dwell on the past, he’s dogged by one burden he carries: He never got to thank all those who cared enough to wish him well. One was a foreign exchange student from Guam who lifted his spirits during some of his darkest days. “I feel very guilty that I’ve never had the chance to thank everybody individually. Many of them are not with us anymore.”

t’s only been in the last few years that he’s reconciled with the scroll, choosing to remember the goodness of Wake Forest people more than the war and pain and loss of that time in his life. Though he does not dwell on the past, he’s dogged by one burden he carries: He never got to thank all those who cared enough to wish him well. One was a foreign exchange student from Guam who lifted his spirits during some of his darkest days. “I feel very guilty that I’ve never had the chance to thank everybody individually. Many of them are not with us anymore.”

Memories come flooding back for Andy Heck, with his dog Sam by his side, as he remembers the kindness of Wake Forest people.

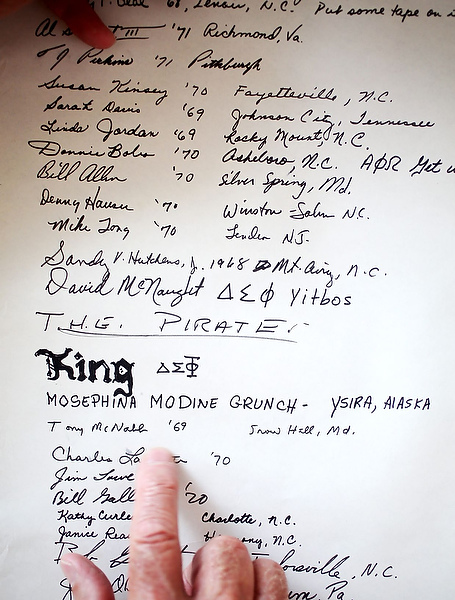

On this day in his sunny kitchen just after Memorial Day, Heck has a lot of people to thank. He’s never counted the number of names on the scroll, but he guesses there must be close to 3,000, which would be most everyone at Wake Forest in the spring of ’68. President James Ralph Scales was the first to sign it. Dean (later Provost) Edwin G. Wilson (’43), Dean of Women Lu Leake, basketball great Charlie Davis (’71, MALS ’97, P ’96) and pioneering Winston-Salem Journal female sports writer Mary Garber signed it, too. Some signed only their nicknames: “Pirate,” “King,” “16” and “Tadpole.”

As he runs his fingers down the list of signatures — people had much neater handwriting back then, he notes — he’s asked to share a few stories about those he remembers. Marnie, his wife of 44 years, is sitting across from him, and pipes up with a laugh: “That’s a mistake.”

He gleefully proves her right. It’s astonishing how many classmates he not only remembers but also has kept up with for nearly five decades. He stops at name after name to share a story — most of them true, he reassures me — about a fraternity brother, a football teammate, a professor, a girlfriend. “If I were to really do this thing right, I’d have my yearbook out and put pictures with the names,” he says, before disappearing into another room to retrieve a Howler to do just that.

He laughs frequently as he reads aloud comments from classmates and friends, from the humorous — “Leave the nurses alone!” — to the serious — “I’ll be joining you soon.” To a classmate who wrote, “I’m glad I’m not there,” Heck replies, laughing, “You’re right about that.” He’s lost in the scroll now, reliving Homecoming, a football game, a class, from the words of friends who experienced each event with him. “Met you briefly at a card game,” one person wrote. Heck says, “I may have owed some of them money,” and offers assurances that he was actually a pretty good card player. “Remember Greek 111 and 112 in ’65 and ’66,” another wrote. “How could I forget?” Heck says. “It was just a little book, how hard could it be?” It was pretty hard, he admits.

He laughs frequently as he reads aloud comments from classmates and friends, from the humorous — “Leave the nurses alone!” — to the serious — “I’ll be joining you soon.” To a classmate who wrote, “I’m glad I’m not there,” Heck replies, laughing, “You’re right about that.” He’s lost in the scroll now, reliving Homecoming, a football game, a class, from the words of friends who experienced each event with him. “Met you briefly at a card game,” one person wrote. Heck says, “I may have owed some of them money,” and offers assurances that he was actually a pretty good card player. “Remember Greek 111 and 112 in ’65 and ’66,” another wrote. “How could I forget?” Heck says. “It was just a little book, how hard could it be?” It was pretty hard, he admits.

A comment from someone he didn’t know causes him to turn serious for a moment. “Although you don’t know me, you can bet I’m pulling for you,” one classmate wrote, echoing so many others’ sentiments. “That was nice,” he says softly.

Football coach Bill Tate, at left; athletics director Gene Hooks (’50), at rear; director of communications Russell Brantley (’45), at right; and two unidentified students unroll the scroll on the Reynolda Hall patio.

A testament to how a campus community came together to support one of its own, the scroll bears witness to unity, despite a divisive war. Heck has plans for it now. He wants to return the scroll to its beginnings and expects to donate it to the Z. Smith Reynolds Library Special Collections and Archives. “I’d like for Wake Forest to see what they’ve done,” he says.

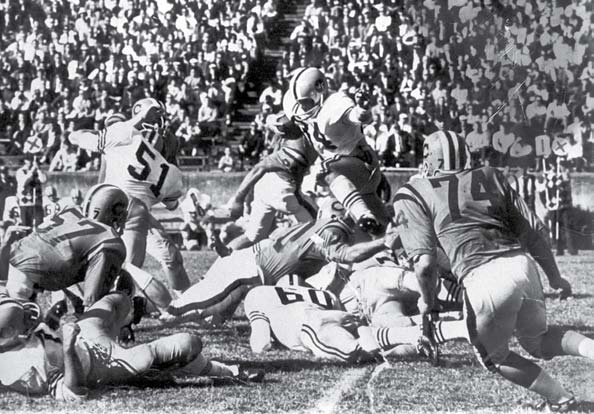

eck’s life began in North Bergen, New Jersey, where he was a tough, squat, street kid who experienced a dose of good fortune early. He survived his first brush with death as a teenager, when a train hit his car. (His buddy, the driver, survived, too.) Heck became a junior college All-American running back in Nebraska, skilled enough to attract attention from major universities. He liked Wake Forest’s small size and strong academics. Coach Bill Tate signed him as the replacement for Brian Piccolo (’65, P ’87, ’89). Heck quickly became one of the few bright spots on teams that struggled to consecutive 3-7 records. The “Old Man,” so named because of his receding hairline, led the team in rushing in 1965 and 1966. In 1966 he won the team’s Most Valuable Player award.

eck’s life began in North Bergen, New Jersey, where he was a tough, squat, street kid who experienced a dose of good fortune early. He survived his first brush with death as a teenager, when a train hit his car. (His buddy, the driver, survived, too.) Heck became a junior college All-American running back in Nebraska, skilled enough to attract attention from major universities. He liked Wake Forest’s small size and strong academics. Coach Bill Tate signed him as the replacement for Brian Piccolo (’65, P ’87, ’89). Heck quickly became one of the few bright spots on teams that struggled to consecutive 3-7 records. The “Old Man,” so named because of his receding hairline, led the team in rushing in 1965 and 1966. In 1966 he won the team’s Most Valuable Player award.

Heck, number 34, was the replacement at running back for Brian Piccolo (’65); no one was tougher than Heck his teammates say.

Heck turned 70 in August, and he maintains a jovial attitude and sense of mischievousness that Wake Forest friends have not forgotten. During his student days, those characteristics led him to spend quite a bit of time with Dean of Men Mark Reece (’49, P ’77, ’81, ’85) and not for pleasantries. He formed strong friendships that endure, especially with his football teammates and Delta Sigma Phi fraternity brothers. “You couldn’t help but like the guy,” says football teammate Bill Angle (’70). “He was the type of guy you could sit beside at Tavern on the Green and not even know him, but within a couple of minutes you felt like you had known him forever.”

He was a Catholic and a “Yankee” at a time when there weren’t many of either on campus, but his outsized personality and fun-loving nature endeared him to classmates. Everyone on campus knew and liked him, says Jody Puckett (’70, P ’00), who was a trainer for the football team. “Andy was one of the big men on the football team, not in terms of stature, but in terms of leadership. He was a tough, tough guy. There was no one tougher than Andy.”

Despite his status as a retiree and senior citizen, Heck looks as though he could suit up in a flash at tailback for the Deacons or re-enlist in the Marines. As he continues reading the scroll’s sprawling list of names, he stops frequently to share more stories of pranks, blind dates, cringe-worthy football injuries and required chapel. He shares one innocuous story from chapel that turned out to be anything but inconsequential. To stay awake in chapel, he stared at a girl who sang in the choir. She had long, dark hair and a birthmark on her neck. He never met her and never knew her name. “It’s the stuff of Ripley’s,” he says, but he’ll finish the story later.

He left Wake after two years to play professional football with the Hamilton Tiger-Cats in the Canadian Football League, rejecting an offer from the San Diego Chargers because the money was better north of the border. His father had died when he was 12, and he felt compelled to help support his mother. He played only a year before he was drafted into the Marine Corps. At a time when some draft-age men were fleeing to Canada, Heck never gave a second thought to answering the call to duty.

He left Wake after two years to play professional football with the Hamilton Tiger-Cats in the Canadian Football League, rejecting an offer from the San Diego Chargers because the money was better north of the border. His father had died when he was 12, and he felt compelled to help support his mother. He played only a year before he was drafted into the Marine Corps. At a time when some draft-age men were fleeing to Canada, Heck never gave a second thought to answering the call to duty.

eck arrived in South Vietnam in January 1968 just a week before the Tet Offensive, a monthlong series of surprise attacks by the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong throughout South Vietnam. He was soon leading patrols with Golf Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines in northern South Vietnam. “Not my idea of golf; I always think of golf at Wake Forest,” he slips in one more joke, looking out his kitchen windows at the golf course on the other side of a creek that runs behind his house.

eck arrived in South Vietnam in January 1968 just a week before the Tet Offensive, a monthlong series of surprise attacks by the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong throughout South Vietnam. He was soon leading patrols with Golf Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines in northern South Vietnam. “Not my idea of golf; I always think of golf at Wake Forest,” he slips in one more joke, looking out his kitchen windows at the golf course on the other side of a creek that runs behind his house.

It was there the Old Man picked up another nickname — “Preparation H,” for always being prepared. “When you land in a hot LZ (landing zone), there’s no question ‘Is someone there?’ ” he says. “You’re dropping into the middle of the fight.” Being careless or lazy could be deadly in the jungle. For the first time all morning while recounting his memories, he grows angry. Fellow soldiers got careless and were killed. He was left to recover their bodies.

Despite his caution, he couldn’t avoid what happened on a night patrol in Quáng Nam Province. A Marine walking in front of him stepped on a booby trap. Heck caught shrapnel in his back, arms and legs and was medevacked to U.S. Naval Hospital Guam. He doesn’t remember how long he had been there when he had a visitor who left him stunned.

“How’d you get here?” Heck remembers asking his visitor. “You got to be kidding me.” Sheila Ramon (’67), the girl from chapel whose name Heck never knew, was standing by his bedside. Ramon had been a foreign exchange student at Wake Forest. Now she was back home in Guam. “I was totally overwhelmed to see Sheila,” Heck says. “I was face down, looking up with one eye, had these IVs in me, and she said, ‘You don’t remember me, Andy. …’ I knew her right off. I’d look at her before I fell asleep (in chapel). I thought I was in trouble for missing chapel.”

“How’d you get here?” Heck remembers asking his visitor. “You got to be kidding me.” Sheila Ramon (’67), the girl from chapel whose name Heck never knew, was standing by his bedside. Ramon had been a foreign exchange student at Wake Forest. Now she was back home in Guam. “I was totally overwhelmed to see Sheila,” Heck says. “I was face down, looking up with one eye, had these IVs in me, and she said, ‘You don’t remember me, Andy. …’ I knew her right off. I’d look at her before I fell asleep (in chapel). I thought I was in trouble for missing chapel.”

Heck doesn’t know how Ramon found him in the hospital. Perhaps one of his football buddies or a fraternity brother had gotten word to her. At the time, he didn’t care; he was just grateful to see a friendly face. “You feel like you’re lost in the middle of nowhere. Even though you’re surrounded by people, there’s no one who understands who you are or where you’re from. Emotionally, it gave me something to latch on to.”

Heck doesn’t know how Ramon found him in the hospital. Perhaps one of his football buddies or a fraternity brother had gotten word to her. At the time, he didn’t care; he was just grateful to see a friendly face. “You feel like you’re lost in the middle of nowhere. Even though you’re surrounded by people, there’s no one who understands who you are or where you’re from. Emotionally, it gave me something to latch on to.”

Ramon visited him frequently. When he was well enough to leave the hospital for short stays, he visited her and her parents at their home. His spirits were lifted, too, by her assurances that Wake Forest remembered him. He didn’t know it at the time, but back on campus classmates were writing him get-well wishes. “Take a minute to send a Get Well message to WFU’s Andy Heck who was grievously wounded in Viet Nam,” read a sign beside the scroll stretched out on the old information desk in Reynolda Hall.

Classmate Sam Gladding (’67, MAEd ’71, P ’07, ’09) remembers signing the scroll. Heck was probably the first, or one of the first, students to be wounded in the war, he says. “Wake was such a small place then. Everybody knew everybody,” he says. “Certainly Andy Heck was prominent, and people liked him.”

Classmate Sam Gladding (’67, MAEd ’71, P ’07, ’09) remembers signing the scroll. Heck was probably the first, or one of the first, students to be wounded in the war, he says. “Wake was such a small place then. Everybody knew everybody,” he says. “Certainly Andy Heck was prominent, and people liked him.”

Heck almost didn’t live long enough to see the scroll. He was sent back to Vietnam a few months later, and the scroll made its way from Wake Forest to Heck’s mother. Heck tried to reach Ramon over the years, but he never found her and never saw her again. (Wake Forest Magazine made several attempts to contact Ramon but got no reply.)

Heck was back in Vietnam for only a month when he was wounded again, shot in the chest during a firefight near Hué. “They put you in a place where a lot of stuff was happening,” Heck says by way of explaining his second injury in less than six months. The corpsman tending to him was shot in the head and killed. He doesn’t offer any more details, preferring to skip ahead to his return to the United States and a refueling stop in Alaska. “I was laying on a stretcher, and I leaned over and kissed the ground,” he says. He chokes up when he tries to describe what happened next when his plane landed at Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington, D.C.

Heck was back in Vietnam for only a month when he was wounded again, shot in the chest during a firefight near Hué. “They put you in a place where a lot of stuff was happening,” Heck says by way of explaining his second injury in less than six months. The corpsman tending to him was shot in the head and killed. He doesn’t offer any more details, preferring to skip ahead to his return to the United States and a refueling stop in Alaska. “I was laying on a stretcher, and I leaned over and kissed the ground,” he says. He chokes up when he tries to describe what happened next when his plane landed at Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington, D.C.

Marnie Heck picks up the story. “The worst thing for Andy was his mother was very sick — she had cancer, but he didn’t know that when he was in Vietnam — and she died shortly thereafter. She didn’t come (to the airport), so there was nobody there for him. All these mothers were meeting either their dead sons or their wounded sons on that plane, and he was left there on a stretcher. One of the other mothers came up to him and hugged him and said, ‘Welcome home, son.’ ”

The scroll is so long that Heck unrolls it on the deck at his rebuilt home in Pawleys Island, South Carolina.

After he recovered, Heck was discharged from the Marines and returned home to New Jersey. He found a package from Wake Forest waiting for him. The scroll was “heartwarming,” he says, but it represented a part of his life that he didn’t want to remember. He packed it away with his Vietnam memories and shoved it under his bed. “I took all my (stuff),” he says, using a more colorful term, “and put it in a box and put it away.”

“My mental state at the time was probably not the best to sit and focus too much on that,” he continues. “The more I looked at it the more overwhelmed I became at the sheer number of people involved and the genuine feelings involved. When you’re going through the names, you’re thinking about that person and wondering what they were thinking. I didn’t spend a lot of time going over this because it had an emotional impact on me, a drawback to a point in my life that I really didn’t want to get into too much.”

![]() nstead of looking back, he moved ahead with his life and returned to Wake Forest. When Groves Stadium (now BB&T Field) opened in September 1968, Heck carried in the American flag during the dedication ceremony. Friends noticed a different Andy Heck. Ralph Lake (’67, P ’98, ’01) remembers being shocked by Heck’s gaunt appearance. “The injury was incredibly serious. Most other people would not have survived it.” Football teammate Bill Angle noticed a change, too: the happy-go-lucky jock was now much more serious about his schoolwork. He didn’t play football again. “Anybody who spent time in ’Nam, you grew up quick,” Angle says.

nstead of looking back, he moved ahead with his life and returned to Wake Forest. When Groves Stadium (now BB&T Field) opened in September 1968, Heck carried in the American flag during the dedication ceremony. Friends noticed a different Andy Heck. Ralph Lake (’67, P ’98, ’01) remembers being shocked by Heck’s gaunt appearance. “The injury was incredibly serious. Most other people would not have survived it.” Football teammate Bill Angle noticed a change, too: the happy-go-lucky jock was now much more serious about his schoolwork. He didn’t play football again. “Anybody who spent time in ’Nam, you grew up quick,” Angle says.

Heck exudes gratitude to those who helped him make the transition from soldier to student including Director of Admissions Bill Starling (’57); football trainer Doc Martin; Dr. David Anderson, a physician with the football team; and Professor of Religion Carlton Mitchell (’43). Mitchell, a former Marine chaplain, once offered the best words of reassurance a Marine returning from an increasingly unpopular war could hear: “Andy, you were meant to be a Marine.”

Heck’s middle son, Dylan (’98), still remembers his father’s pride in being a Marine. His dad would wake him and his brothers Cameron and Ryan with the Marine Corps anthem and “Let’s go, men!” But he never talked much about his service. The scroll didn’t mean much to Dylan in childhood. But after the fire destroyed the Hecks’ house a decade ago, Dylan realized how much the scroll meant to his father. “He didn’t have much family, and Wake became a family to him. It’s a testament to how many people from Wake loved my dad.”

From the rubble, Heck recovered the scroll, two Howlers and some photos from his football days, all of which had been stored in the garage. His Marine dog tags turned up in the ruins of a bedroom. The house we are in on this morning is the rebuilt home.

Heck can look back with satisfaction on a flourishing business career with International Paper Co. and his time as president of Sylvania Lighting US. He retired a success eight years ago. Now he’s at a point in his life when he wants to think about his legacy, not legacy in the typical sense, but leaving a legacy of gratitude. The scroll “has been a very, very meaningful part of my life,” he says. “It’s been lying dormant for different reasons, but not for lack of gratitude. I would like to say to everybody who’s on there: Here’s something that you wrote x number of years ago; think about who you were then and who you are now, and the gratitude of the guy that you wrote it to.”

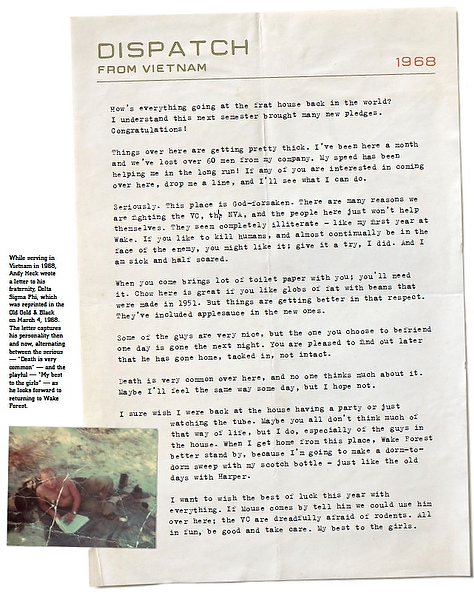

Dispatch From Vietnam, 1968

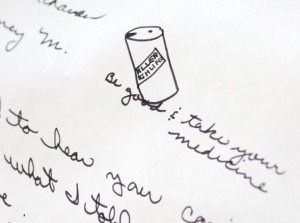

While serving in Vietnam in 1968, Andy Heck wrote a letter to his fraternity, Delta Sigma Phi, which was reprinted in the Old Gold & Black on March 4, 1968. The letter captures his personality then and now, alternating between the serious — “Death is very common” — and the playful — “My best to the girls” — as he looks forward to returning to Wake Forest.

How’s everything going at the frat house back in the world? I understand this next semester brought many new pledges. Congratulations!

Things over here are getting pretty thick. I’ve been here a month and we’ve lost over 60 men from my company. My speed has been helping me in the long run! If any of you are interested in coming over here, drop me a line, and I’ll see what I can do.

Seriously. This place is God-forsaken. There are many reasons we are fighting the VC, the NVA, and the people here just won’t help themselves. They seem completely illiterate – like my first year at Wake. If you like to kill humans, and almost continually be in the face of the enemy, you might like it; give it a try, I did. And I am sick and half scared.

When you come brings lot of toilet paper with you; you’ll need it. Chow here is great if you like globs of fat with beans that were made in 1951. But things are getting better in that respect. They’ve included applesauce in the new ones.

Some of the guys are very nice, but the one you choose to befriend one day is gone the next night. You are pleased to find out later that he has gone home, tacked in, not intact.

Death is very common over here, and no one thinks much about it. Maybe I’ll feel the same way some day, but I hope not.

I sure wish I were back at the house having a party or just watching the tube. Maybe you all don’t think much of that way of life, but I do, especially of the guys in the house. When I get home from this place, Wake Forest better stand by, because I’m going to make a dorm-to-dorm sweep with my scotch bottle – just like the old days with Harper.

I want to wish the best of luck this year with everything. If Mouse comes by tell him we could use him over here; the VC are dreadfully afraid of rodents. All in fun, be good and take care. My best to the girls.