There was a whole lotta shakin’ goin’ on at Wake Forest on Nov. 20, 1957. Some described it as a riot, fueled by Elvis Presley, Ritchie Valens and Buddy Holly. The day would go down as a “red-letter day in the history of Wake Forest,” the Old Gold & Black predicted.

It was the day that the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina reaffirmed its ban on what it deemed a demoralizing and immoral practice: dancing. Dancing had first been banned in 1937, although fraternity dances quietly took place off campus. In early 1957, Wake Forest trustees voted to allow chaperoned dancing on campus despite the ban. Convention leaders objected, leading to a showdown at the convention’s annual meeting. Eighty-five percent of delegates, in a “thunderous voice vote,” upheld the ban, according to the OG&B.

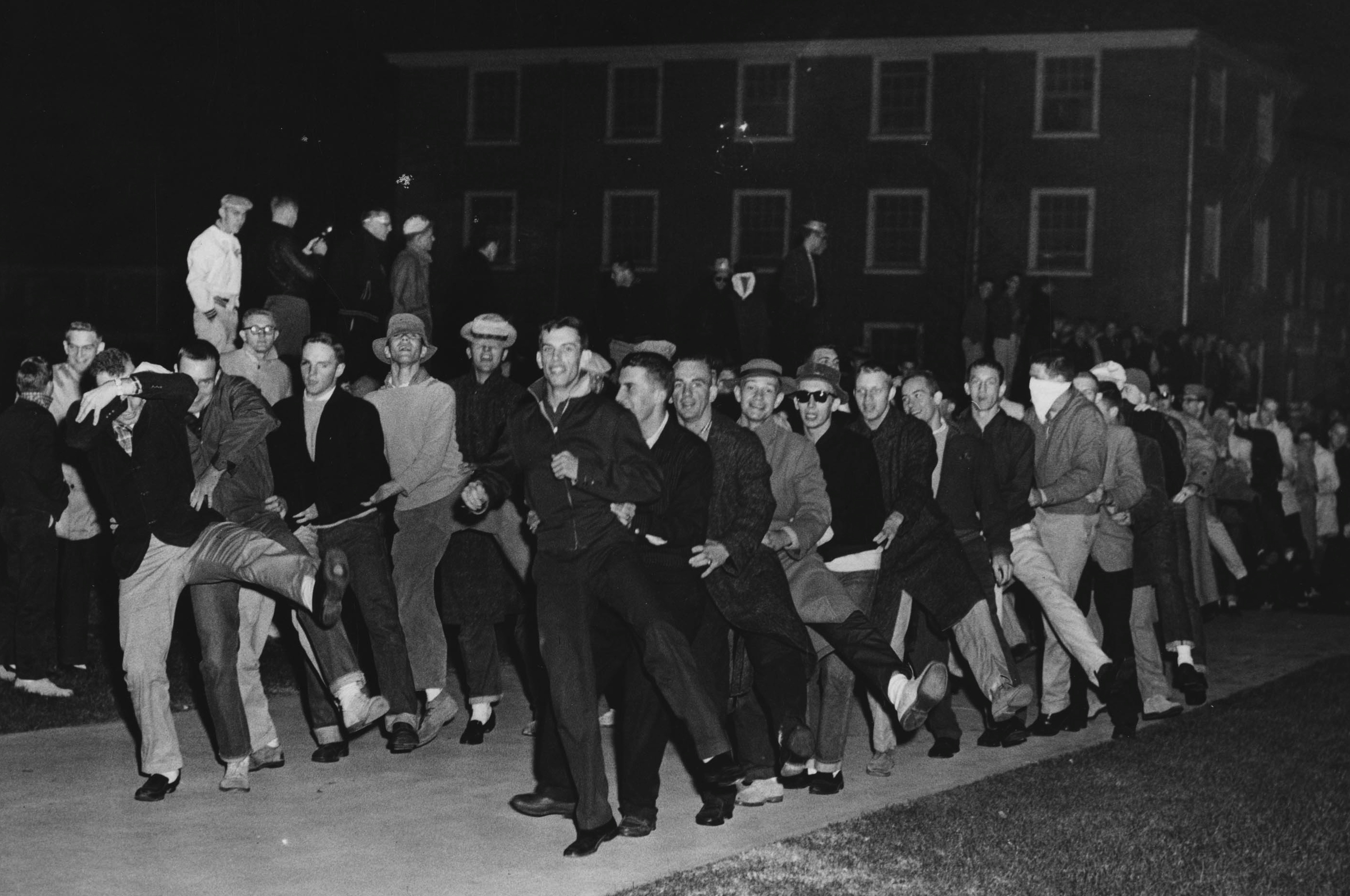

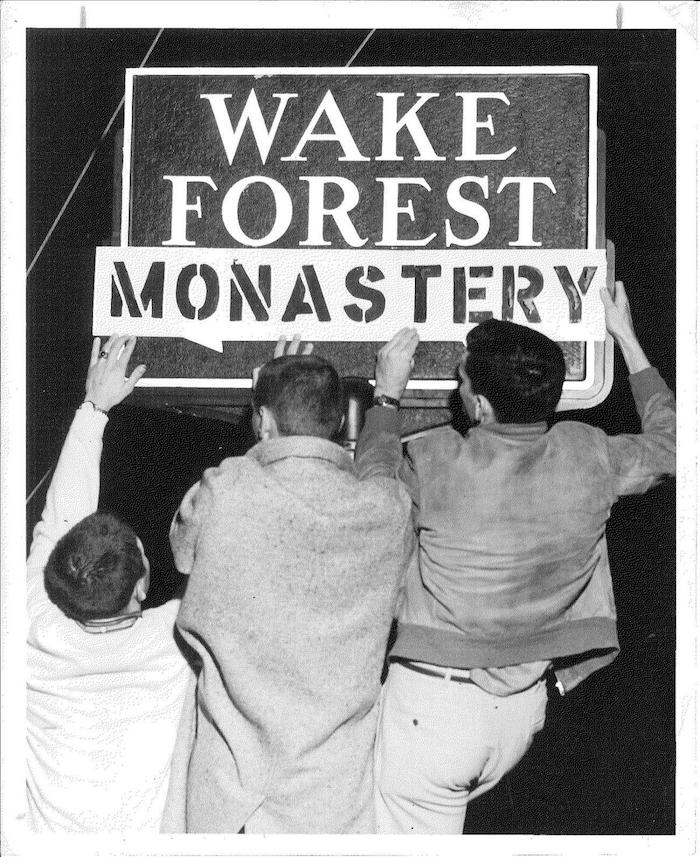

The vote “set off the rockingest dance Wake Forest College is ever likely to see,” read newspaper stories the next day. After a bugler sounded “Charge!,” 1,000 students rushed to the Quad, shouting, “We wanna dance!” They rolled the trees with toilet paper, shot off fireworks, set a bonfire, burned an effigy of the convention president and changed the campus entrance sign to “Wake Forest Monastery.” Most of all they danced, doing the bunnyhop and the jitterbug and rocking to “Wake Up Little Susie” and “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On.”

Photo courtesy of Forsyth County Public Library Photograph Collection

LIFE magazine devoted two pages to the protest under the headline “Students blew up in rebellion.” Some students hid their faces in photographs, but others were defiant. “It was more fun than a panty raid,” one coed said. “We ought to go dance with these old men and see if they get all shook,” another coed said, speaking of Baptist leaders. The New York Times and Dave Garroway’s “Today” show covered the protest.

At compulsory chapel the next morning, coeds wore red paper “Ds” on their sweaters. An alert janitor foiled a plan to play “I Could Have Danced All Night” on a hi-fi connected to Wait Chapel’s public address system. But after an alarm clock rang, the entire student body walked out en masse, singing, “Dear Old Wake Forest.” Some outsiders blamed music professor Thane McDonald for the walkout after a wire service report alleged that he sped up the tempo of a hymn, “Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing,” to a “danceable tempo.” McDonald denied speeding up the hymn.

After leaving chapel, students marched to Reynolda Hall, yelling, “15 rahs for Arthur Murray!” They carried a jukebox out of the soda shop that was then adjacent to the Reynolda Hall patio and began dancing. “Coeds, dressed in black to mourn the death of dancing, seemed unwilling at first to dance to the jukebox music,” the OG&B reported. “The fear of authority melted as the music became stronger and several couples started to rock and roll.” Dean William C. Archie (MA 1935) eventually asked the students to “cease and desist” any more protests.

Photo courtesy Forsyth County Public Library Photograph Collection

But the protest reignited that night when several hundred students went to Thruway Shopping Center, chanting, “We want to dance.” Someone connected a loudspeaker to a car radio and students were soon doing the bunnyhop across the parking lot. “Although female partners were scarce, the students danced several numbers,” the Winston-Salem Journal reported.

The uproar soon faded, although the issue resurfaced from time to time during the ’60s. When James Ralph Scales became president in 1967, he loosened many longstanding social policies that irritated students. He quietly lifted the dance ban without asking permission from the trustees or the convention.

“Dancing on campus would now be allowed, not as the result of some public declaration but simply by the University’s choosing no longer to pay any attention to it,” Provost Emeritus Edwin G. Wilson (’43) wrote in “The History of Wake Forest University, Volume V.”

At Homecoming in 1967, Bob Collins and the Fabulous 5 “played at a dance in — of all places — the main lounge of Reynolda, revealing a new change of attitude,” the OG&B reported. And students have danced on campus ever since.

Students put up a sign reading Wake Forest Monastery to protest the dance ban.