![]() avid Bland (’76, P ’04) wound his rental car south on Interstate 15 through the cold, clear Montana night. Somewhere between Great Falls and Helena, Bland pulled the car off the winding highway. He stepped into the wintry darkness, frustrated from a day of contentious meetings, and lifted his gaze to a sky full of stars.

avid Bland (’76, P ’04) wound his rental car south on Interstate 15 through the cold, clear Montana night. Somewhere between Great Falls and Helena, Bland pulled the car off the winding highway. He stepped into the wintry darkness, frustrated from a day of contentious meetings, and lifted his gaze to a sky full of stars.

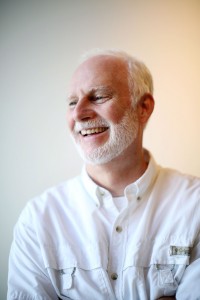

Suddenly, his role as community reinvestment manager for the Federal Reserve, combined with his experience running a low-income housing development nonprofit, clicked. “Literally, it came to me in a flash,” Bland says of that moment of inspiration two decades ago. “Oh, my gosh,” he thought. “I know how to do this myself.” With that, Bland’s singular startup, Travois — a finance company destined to build a better future for thousands of Native Americans — was born.

“Literally, it came to me in a flash … I know how to do this myself.”

At the time of his revelation, the Norfolk, Virginia, native and aspiring cowboy was working for the Ninth Federal Reserve District in Minneapolis, charged with persuading banks to “do well by doing good.” His territory ranged 1,800 miles from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula across Wisconsin and Minnesota, through the Dakotas and into Montana. Earlier on the day of his epiphany he had met with bankers in Great Falls, Montana, who balked at investing in nearby Indian reservations in desperate need of quality, affordable housing. To traditional financial institutions, those impoverished communities were too remote, too risky.

Bland founded Travois in 1995 to help tribes take advantage of the federal government’s Low Income Housing Tax Credit Program, which provides developers an incentive to encourage private entities to invest in affordable housing — federal tax credits. Developers whose eligible projects are awarded a portion of millions in federal tax credits can sell the credits to investors to raise capital. This reduces the amount developers must borrow, ultimately lowering the rents they will charge tenants while easing the tax burden for investors. Bland believed that this little-known investment tool could bridge cultural barriers that hampered Native American tribes’ economic growth, from tribal distrust of non-native businesspeople to lenders reluctant to make Indian Country loans.

“My work at the Fed taught me that all of these fears were, in fact, myths,” Bland says. Over time, Bland built relationships, navigated reservation regulations and secured collateral. Where most might see insurmountable challenges among the nation’s 566 federally recognized tribes, Travois saw hope.

Michelle J., her husband, Harry, and their children, Jerwin and Amber, members of the San Carlos Apache Reservation in San Carlos, Arizona, understand the transformative power of Travois’ work. Travois helped the tribal housing authority secure Low Income Housing Tax Credits to rehabilitate 25 homes and design and build 16 more in 2013, including Michelle’s.

“It’s beautiful the way we are living,” said Michelle J., pictured here with her family in San Carlos, Arizona. (Photo by ©Rick Brazil, Brazil Design Group)

Previously, Michelle and her family battled spiders and sugar ants crawling in her son’s bed. Without proper heating and cooling, the family suffered through withering summers and frigid winters. Now, their new three-bedroom, two-bathroom home features reliable air conditioning and heat, ceiling fans, solar panels, an open kitchen with energy-efficient appliances, and more space and privacy, keeping the family comfortable and safe in the community they love.

“It’s kind of like a relief that we have this house,” said Michelle, whose cousin lives in an overcrowded home of 15 relatives. “It’s beautiful the way we are living,” she said. “Things are much easier.”

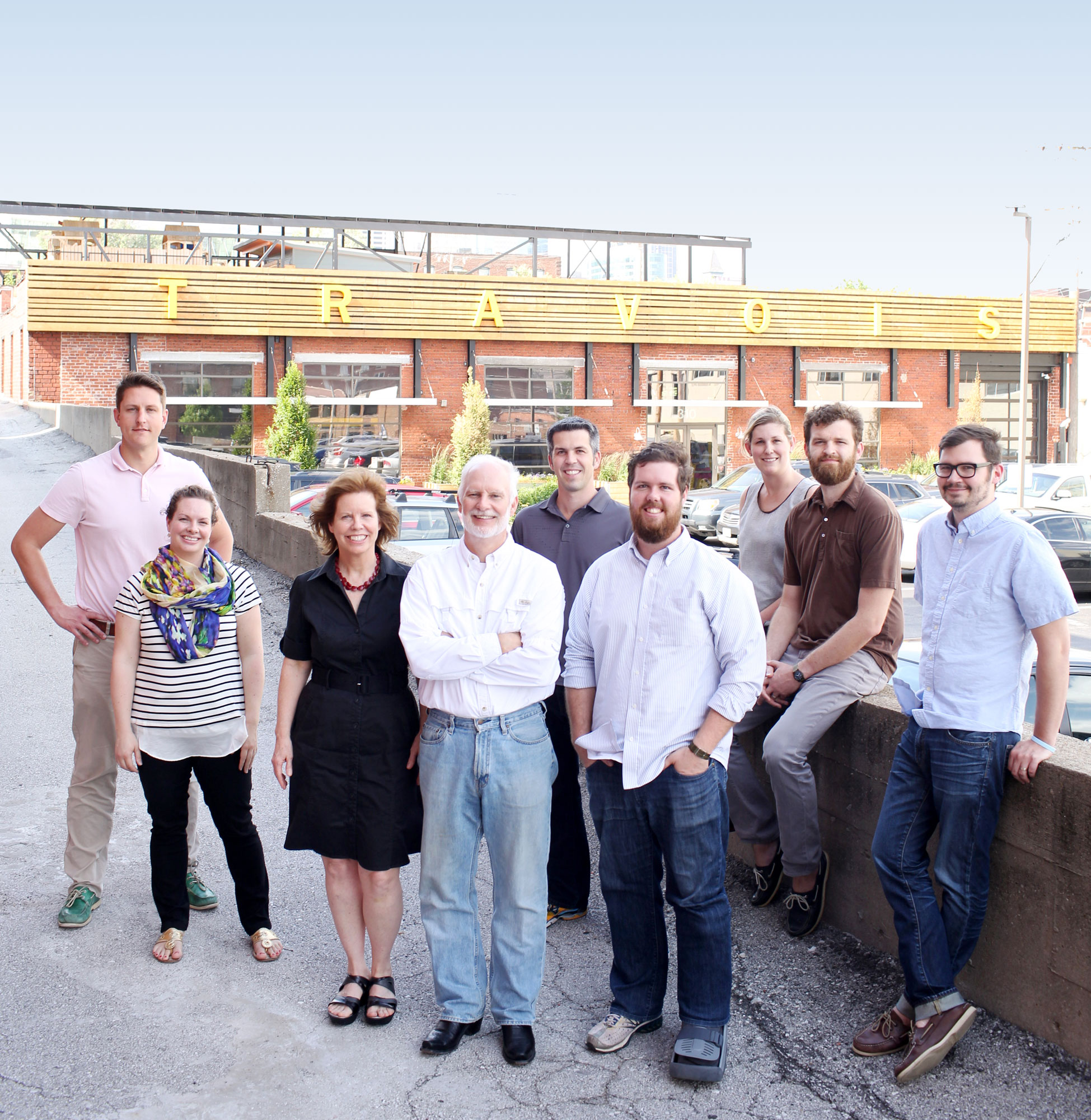

Since the early days crisscrossing the plains earning tribal leaders’ trust, Bland has grown the Kansas City, Missouri-based company to 30 full-time employees who have spearheaded $1 billion worth of economic development projects for scores of native groups. Travois’ work has led to the creation of thousands of jobs and construction of thousands of new and rehabilitated homes for tribal families. Travois financing and consulting has helped back an array of projects: early childhood education centers, salmon processing plants, dental clinics, centers for young people seeking refuge from abusive situations, a college athletic center and sweat lodge, and communal living spaces for tribal elders — among others — in Native American communities across the country.

Spotting untapped potential was nothing new for Bland; his daughter, Elizabeth Bland Glynn (’04), describes him as the “quintessential entrepreneur.”

“It takes a special person to be able to take that risk and jump out into the ocean,” says Bland Glynn, chief operating officer at Travois. “He knows how to start something from scratch.” Bland’s entrepreneurial spirit was propelled by his passion for social equality. Bynum Shaw’s journalism class introduced Bland to “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” by Dee Brown, the searing history of 19th century injustices against Native Americans. The book, Bland says, “changed my life.” Today, he asks all Travois staffers to read it.

Travois’ modern headquarters in Kansas City’s Crossroads Arts District features 330 solar panels.<br />

“Travois is known throughout Indian Country,” said Richard Litsey, policy director for the National Indian Health Board, a nonprofit health advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C. “They just do terrific work with tribal entities, whether it’s providing homes and houses or economic development.” Litsey, an enrolled member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, first met Bland in about 2007, when Litsey worked as counsel and senior adviser for Indian Affairs for the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, then chaired by former Sen. Max Baucus (D-Mont.).

“They have an extremely good reputation working with tribes,” Litsey said. “Housing is always a problem in Indian Country. … We have a severe shortage of housing. Again, the funding that David supplies for low-income housing makes a tremendous difference.”

“I really admire what he does and how he does it.”

“They have a track record of strong community impacts in some of the most difficult to develop communities in the United States,” said Chris Sears (’01), a first vice president at SunTrust Community Capital, LLC, who specializes in community reinvestment. “Everything they do is extremely out of the box compared to more traditional real estate or investment transactions.”

Bolstering this creative approach to economic development, Bland shaped Travois’ ethos into one of collaboration. The company is careful to avoid swooping into native communities with all the answers. Instead, the employees listen and learn to help local leaders generate local solutions. The company name, logo and motto reflect that community-based grassroots approach. A travois is a frame of poles that Plains Indians used to transport heavy loads; Travois’ motto is “You know where you want to go, let us pull some of the weight for you.”

As Bland expanded Travois’ reach, he transformed his vision into a thriving family business. In addition to Bland’s daughter Elizabeth, wife Marianne Roos is vice chairman, son-in-law Phil Glynn (’03) is vice president for economic development, son Greg Bland is environmental services director, and nieces and nephews serve in various leadership roles.

“In the final analysis, this is a family company,” Bland says. “Our strength is derived from the love that we have for each other, the mission that we all share to really leave our mark on the world.”

Beyond that shared passion and purpose, working with your closest relatives means “nobody in the family wants to let anybody down.” That strong foundation has enabled the company to diversify from housing into divisions focused on design and construction, environmental services, economic development and asset management.

Travois takes the idea of social good seriously: helping people thrive begins with its own employees. The Bland family has worked hard to foster an environment where people are empowered to do their best work. “We’re creating a home for our employees for the time when they’re here during the day,” Bland Glynn says. “We try to make things be as welcoming and inviting as I would like my own house to be.”

Travois’ family-friendly philosophy means on-site day care for employees and a rooftop playground for their children.

That means comfy furniture and a pool table; free healthy (and unhealthy) snacks; dogs roaming the office; an on-site day care and rooftop playground so employees can stay close to their kids; Friday lunches and guest speakers to build community; ample volunteer opportunities; and 330 solar panels to keep the roughly century-old building sustainable.

Travois has “high expectations for our staff and a lot of important deadlines and stressful work,” Bland Glynn says. Occasional barking on a conference call, dogs gobbling up crumbs dropped by employees’ children, and little ones cruising by meeting rooms in tiny foot-propelled cars take the edge off difficult days.

“By giving people the dignity to live their lives and know they’ll take care of you, the workplace is giving them an interesting reason to get out of bed in the morning,” Roos says.

Travois also takes pains to showcase the Native American cultures the company supports, housing a major collection of contemporary Native American art.

“We want to reflect the artistic strivings of Indian Country,” Bland says. “We want people to walk the hallways in our building and see some of the beauty that emerged from Indian Country. So much of what we do is the exact opposite: It’s so sad, it’s so heartrending, you need to look at something that lifts you up on occasion, too.”

Working alongside her father has offered Elizabeth Bland Glynn perspective on her parents that most children miss.

“I remember traveling with my dad when I was little, and he would speak to a room full of people,” she said. “I always was in awe of how he could speak to so many people and convince them to do these important things to change their community.”

The Bland family’s commitment to building healthier, sustainable communities extends from the offices of Travois to Indian reservations across 20 states. Having worked for years in nonprofits, Bland acutely understood the potential shortcomings of philanthropy to effect large-scale change.

As a 501(c)(3), “you have to go hat in hand,” he says. “That’s a really limited way to raise capital.” Instead, he envisioned transforming the affordable housing landscape through access to capital markets and social entrepreneurship.

“We were social entrepreneurs before there was even a term for social entrepreneurship,” Bland says. “We wanted to do something that wasn’t just making a living for ourselves.” Carving out a unique market niche, Travois jumpstarted the housing market across Indian Country on an unprecedented scale, growing into a mission-driven company committed to doing well and doing good.

“We were social entrepreneurs before there was even a term for social entrepreneurship,” Bland says. “We wanted to do something that wasn’t just making a living for ourselves.” Carving out a unique market niche, Travois jumpstarted the housing market across Indian Country on an unprecedented scale, growing into a mission-driven company committed to doing well and doing good.

“I’m really proud of what our clients can do,” says Bland’s son-in-law Phil Glynn, vice president for economic development. “I think there’s just so much negativity out there about what’s happening in Indian Country, so much fatalism about what’s happening in low-income communities. There are problems, but there are also people there who are succeeding in life. They’re successful in their own lives changing the circumstances of their entire communities.”

Company founder Bland is eager to spread across Missouri the gospel of this triple bottom-line model focused on social, environmental and financial progress. He is advocating for state legislation recognizing so-called benefit corporations — for-profit businesses dedicated to social and environmental good.

“He sees opportunity everywhere,” Roos says.

Travois’ American Indian art collection showcases prominent native artists and has been featured on community art walks.

Bland, a political science major, can trace his deeply held passions for market-driven progressive change to Wake Forest classrooms. Several courses “left an indelible mark on me that drove me to just be who I am,” he says. In the late Assistant Professor William E. Cage’s economics of social equality course, conservative and liberal students literally sat divided on the right and left sides of the classroom as Cage moderated crackling debate on inflation and a living wage. According to Cage, “Inflation is the price civilization pays for social justice; if you’re not willing to pay for things, you’re not willing to address poverty,” Bland recalls. “It got me thinking: ‘What can I do as a person that will at least not hurt anybody?’ ”

The late Professor Emeritus of English Tom Gossett’s ruthless rejection of cliché and enforcement of good grammar drowned Bland’s first paper in red ink — and forced him to think analytically. And the late C.H. Richards Jr.’s demanding constitutional law class covered President Andrew Jackson and the Trail of Tears — which Richards labeled one of the darkest moments in American history — sparking Bland’s belief “that we have a responsibility through the Constitution to make sure the rights of minorities are protected.”

Bland hails from an East Coast shipping hub, but he has always enjoyed a romance with the West, finding happiness on horseback.

“He wore a cowboy hat from before I was born,” Bland Glynn says. “I think that he has always wanted to be a cowboy. He’s always pushing that frontier, always wanting to discover the next new thing.”

Unsurprisingly, Bland has big ideas for Travois’ next frontier. He is intrigued by a burgeoning movement in social impact bonds, financial vehicles to help address problems like the chronic health conditions that plague Native Americans. Indians suffer disproportionately high rates of infant mortality, diabetes, substance abuse and suicide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Among the Travois team are Wake Foresters and Bland family members who include from left to right: son-in-law Phil Glynn, daughter Elizabeth Bland Glynn, Marianne Roos and founder David Bland with their son Greg Bland on the front row.

Investing earlier to build wellness infrastructure in native communities — such as improving access to healthy food and fitness resources — would ultimately reduce the cost of long-term care and the drain on strapped Indian Health Service facilities, Bland says. This model could extend to substance abuse, a serious problem across Indian Country, resulting in more rehabilitation centers and systems on reservations.

He’s not the only one at Travois thinking big. Glynn sees the company expanding into new states and diversifying into more tribal-owned private enterprise. Bland Glynn envisions working with indigenous communities overseas. There’s a possibility of helping tribes build alternative energy infrastructure such as wind turbines and invest in carbon-offset credits. The opportunities are vast; father and daughter are dedicated to leading Travois into the future, together.

“That’s definitely something that I would like to grow into doing,” says Bland Glynn, recently recognized as a NextGen Leader 2014 by the Kansas City Business Journal. “Dad started this amazing company, and I’m really excited to see how I can continue his dream.”

Ancient Communities, Modern Amenities

Travois partners with and helps to empower a diverse array of creative entrepreneurs across Native American reservations. Some of the transformative projects supported by Travois include:

• Goodnews Bay Regional Processing Plant: Run by Alaskan tribes, their flash-frozen salmon caught using ancient techniques is in demand in Seattle, Los Angeles and Tokyo.

• Little Big Horn College in Montana: The Crow Tribe of Indians’ college built a gymnasium, locker rooms and exercise areas in the new 35,000-square foot campus health and wellness center, in addition to saunas for student athletes to keep sweat lodge traditions alive.

• Educare: This Winnebago, Nebraska, program provides 191 low-income infants to preschoolers intensive year-round education to prepare them for school.

• Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Community Dental Facility: This Wisconsin tribe’s state-of-the-art, architecturally modern dental clinic trains dental hygienists and dentists — and attracts patients from beyond the reservation.

• Itom Hiapsi: A health, wellness and community center for Arizona’s Pascua Yaqui Tribe offers holistic medicine, legal services, GED programs, language preservation and tribal history resources, gathering spots for elders, plus a recording studio and DJ equipment for young people to use after school.

• Wastewater Improvements: Rehabilitating the New Mexico Pueblo of Laguna’s aging water treatment systems that serve six villages means safer, more plentiful drinking water and increased firefighting readiness.

Susannah Rosenblatt (’03) was a Nancy Susan Reynolds Scholar at Wake Forest. She spent six years as a reporter at the Los Angeles Times and is now director at Reingold, Inc., a communications firm in Alexandria, Virginia.