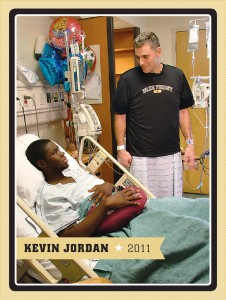

It will take more than a life-threatening illness, transplant surgery and a fifth year of college to make up for lost time to put the brakes on Kevin Jordan’s dream of playing professional baseball. The Atlanta Braves cap on his head, with its distinctive red “A” logo, hits such a notion out of the park.

In the inspirational story of this Wake Forest outfielder, the A may very well stand for Attitude — as in positive. Or for his A game — as in a mindset instilled in him by a loving family. Both A’s, it turns out, have been modeled for him every day for the last five years by his coach, Tom Walter, the man whose kidney saved Jordan’s life.

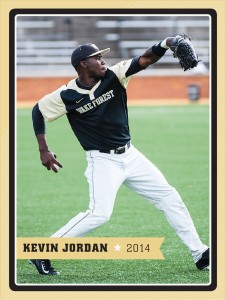

Four years after the February 2011 transplant surgery, the two remain connected, physically and emotionally, by more than a vital organ; they share drive, commitment and a mutual dream: that after Jordan’s graduation in May, he’ll get his chance to play in the Major Leagues. “He deserves a chance to play,” says Walter. “He has the physical skills and the mental wherewithal to do it.” Jordan thinks his story would inspire others to never give up on their dream. “I was blessed with great talent,” he says. “I know I was a great player and I can still play on that level. Whether I get a shot or not, we’ll see.”

It was 2010, Jordan’s freshman year, when doctors determined the star athlete from Columbus, Georgia, suffered from an autoimmune virus, which was attacking his body and zapping his strength. From January to June he had gone from being a first-round draft pick by the New York Yankees out of high school to a sick student on a college campus 400 miles from family. He barely knew anyone and had already dropped 40-some pounds from his once 180-pound frame.

It was 2010, Jordan’s freshman year, when doctors determined the star athlete from Columbus, Georgia, suffered from an autoimmune virus, which was attacking his body and zapping his strength. From January to June he had gone from being a first-round draft pick by the New York Yankees out of high school to a sick student on a college campus 400 miles from family. He barely knew anyone and had already dropped 40-some pounds from his once 180-pound frame.

Jordan could have given up and gone back home, but those A’s kicked in — along with the voice of his grandfather reminding him how much he loved to watch his grandson play baseball. He stayed in school, carried a full class load, attended baseball practice although he couldn’t play, then returned to his room every night to hook himself up to a dialysis machine that ran until 8 a.m. Most people can’t understand what such a transformation does to someone, says Walter, and he wonders how many 18-year-olds would have made a similar decision.

Instead of feeling sorry for himself, Jordan focused on how fortunate he was to have loving parents and grandparents. And great genes. “I didn’t have a lot of adversity when I looked at other people’s lives,” he says. “Before all that happened I felt like I had been given so much.”

The day came when his body needed a replacement kidney, and this time it was Walter who brought his A’s. Impressed with the young man’s courage and resilience, he did what he modestly says any coach would have done to help a player succeed. He offered the ultimate resource: his own kidney. Walter says there was never any hesitation on his part. His intuition told him he was the one, put in the right place at the right time. “It was just one of those things; sure it was a long shot but it was meant to be,” he says. As fate would have it, Walter — who has since become an outspoken advocate for organ donation — was an excellent match. Better, even, than Jordan’s own mother.

While the absence of a healthy kidney has not altered the coach’s active lifestyle, the presence of one has changed the player dramatically. Now 23, he’s gained 60 pounds, back up to 200 pounds of solid muscle mass. Jordan remains more vulnerable than most of us to bugs and viruses that make the rounds, so he must maintain a strict regimen of diet and exercise. Aside from Jordan’s physical changes, Walter has also noticed a change in his maturity. “He has a calm presence about him that some people might mistake for apathy. But it’s not at all because he doesn’t care, because he’s one of the players that cares most,” says the coach. “Sometimes it just comes across that way because he’s so mature and introspective.” Living a lifetime in your first 18 years might do that to a person.

While the absence of a healthy kidney has not altered the coach’s active lifestyle, the presence of one has changed the player dramatically. Now 23, he’s gained 60 pounds, back up to 200 pounds of solid muscle mass. Jordan remains more vulnerable than most of us to bugs and viruses that make the rounds, so he must maintain a strict regimen of diet and exercise. Aside from Jordan’s physical changes, Walter has also noticed a change in his maturity. “He has a calm presence about him that some people might mistake for apathy. But it’s not at all because he doesn’t care, because he’s one of the players that cares most,” says the coach. “Sometimes it just comes across that way because he’s so mature and introspective.” Living a lifetime in your first 18 years might do that to a person.

For Jordan, a communication major, playing pro ball would be a dream come true. But if it’s not in the cards, he says he won’t be bitter. “I’m putting in all the work now,” he says, “so I won’t be disappointed.” Eventually he’d like to be a sports agent, getting an athlete’s voice into the business. “I would have a lot of fun. A lot.”

Beneath their strong, stoic exteriors simmers an emotional bond, one Jordan and Walter are reluctant to acknowledge because, for now, theirs must remain a player-coach relationship.

Jordan, flashing an engaging smile, says that now is not the time to blur the lines.

“When you’re playing against an ACC opponent and you’re subbed out in the ninth inning because you’re not having a good game, that’s not the time for me to be thinking about if he gave me a kidney or not. But I guarantee it will be a lot easier when I’m done playing for him.”

“We’ve both done a very good job of focusing on the task at hand; ballplayers are usually good at that,” says Walter. “Neither one of us has sat back and looked at the big picture. I’m sure at some point there’s going to be one of those moments.”

If a hint of mist in the eyes or the suggestion of a lump in the throat is any indication, the time will come soon enough when they open up about those feelings that, for now, only their mothers — who keep in touch — can express.

Envision it happening at a Braves ballpark where, having been brought together by destiny and bound by fate, they meet once again — this time as friends rather than player and coach. And at least one — the outfielder — is wearing an “A” on his cap. Officially.

As their sons went through the before, during and after process of kidney transplant surgery in February 2011, Charlene Jordan and Anne Walter shared a life-changing experience of their own. An emotional bond, born of phone conversations about lab results and nurtured during hours of waiting, worrying and walking to and from the hospital cafeteria or bookstore, to this day connects the mothers of donor Tom Walter and recipient Kevin Jordan.

“We met in person for the first time on the day of surgery, and it has evolved from there,” says Charlene. “She’s a sweet and caring person — someone easy to have a special relationship with.”

“Before the surgery we talked on the phone once a week; a little more after the surgery because it was like nobody else really knew what we went through. She and I were at the hospital for all those days in Atlanta; we were worried, and we leaned on each other.”

Four years have passed and Charlene and Anne stay in touch via email and regular phone conversations — about their sons, who are thriving — but also about family, causes they support, recipes and other things in life. “I can talk to Charlene on the phone for an hour,” Anne says. “She’s a sweetie. She had a lot of courage, too.”

Charlene Jordan, left, and Anne Walter after learning their sons were out of surgery and doing well. (Courtesy Anne Walter)<br />

Their close-knit families are separated by hundreds of miles — the Walters live in Winston-Salem and the Jordans in Georgia — but they get together when the Jordans are in town for Wake baseball games.

When she first met the Jordans, says Anne, she realized she could have been the one with the son who needed a kidney. “I was cheering them on. We were so grateful that Tom could do it because it was easy to put ourselves in the Jordans’ position.”

Charlene says her family, in turn, is grateful to Tom and his whole family because he took a risk that affected them. She’s also glad Anne is in town to keep an eye on Kevin. “When I see Kevin on campus he always gives me a big hug,” says Anne, “and I always ask him, ‘How’s my kidney doing?’ ”

A while back Charlene called Anne to let her know the big news that another of her children had gotten a job. Anne noted that pretty soon it would be Kevin, who graduates May 18, and Charlene said she couldn’t wait for that day. Neither can Anne.

Now that they’re all part of each other’s families, the Jordans and the Walters will be sitting together at Commencement — celebrating another life-changing moment with their two sons: one whose future looks bright, the other whose selflessness made that possible.