ON A JULY MORNING

______

in a Washington, D.C., suburb, the local branch of the Veterans Curation Program was having an open house. The VCP trains ex-soldiers to work in an archaeology lab, and on this day, a dozen recent veterans stood behind their neat desks, describing their work to a steady stream of visitors. One veteran operated a 3-D digital camera. Another stood, his back military-straight, over a display of catalogued artifacts.

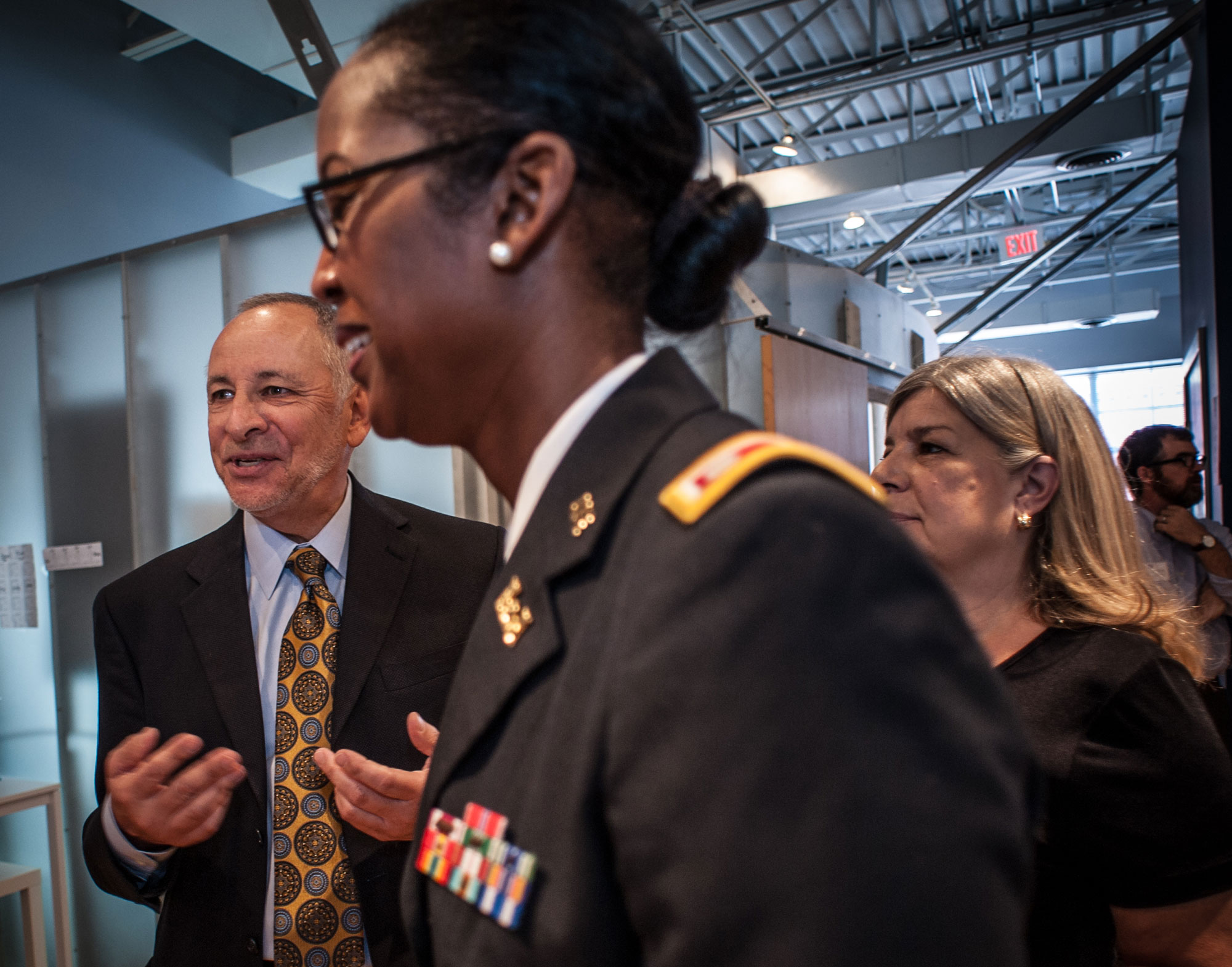

In one corner of the vast, open office, an assistant secretary of the Army was extolling the program’s virtues: It has a remarkable 87 percent success rate in transitioning veterans to civilian jobs or higher education. Across the room stood the program’s founder, Michael “Sonny” Trimble (’74). Trimble wore a suit and tie, but he had the suntan and active stride of a man who works outdoors. He was talking about windows.

“Typically an archaeology lab has zero windows,” he said. “I mean, I grew up in basements. But we made this one different on purpose — light, airy.” Trimble gestured toward a wall of windows. The sun was streaming in. “In Iraq, you’re exposed to bullets all the time. You’ve got mortar shells coming over the wall of the base while you sleep. You learn to hate windows.”

Trimble gives visitors a tour of the Veterans Curation Program offices in Alexandria, Virginia.

Though Trimble is an archaeologist with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, he spent most of 2004-2007 on civilian assignment in Iraq, often under the protection of American soldiers. Like them, he traveled in convoys on exposed roads; like them, he dived for cover when shells came over the wall. “Most veterans get PTSD,” he said. “I had it, too. When I came home, for a year, I used to sit in my house all weekend. I was afraid to go out.”

After he got back, Trimble thought a lot about the soldiers who had kept him alive in Iraq. He wondered what would happen to the ones who didn’t become cops or firemen, what kind of jobs they might do. The Corps of Engineers had millions of artifacts to archive. The military had thousands of veterans needing jobs. Trimble figured he could train some of the veterans to work in his archive, and along the way, teach them the basics of office work in the civilian world.

Recently separated veterans work to catalogue some of the millions of artifacts curated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Now Trimble scanned the row of desks. As they often do, his eyes shrewdly took the measure of the scene before him. A few months ago, most of the veterans at these desks had been at the low points of their careers. Now they stood in front of a bank of exposed windows, explaining their highly technical work with ease.

“I’m a big believer,” Trimble said, “that if a guy wants to learn something, he’d better do it himself.”

******

In the summer of 2004 Sonny Trimble flew over the Tigris and the Euphrates in a Black Hawk helicopter. Like any archaeologist, he felt a rush of excitement as he glanced down on the cradle of civilization. But the chopper pressed on. Trimble and his team were headed deep into the Ninawa desert, where in the late 1980s Saddam Hussein’s forces had executed — and buried — at least 50,000 Kurdish civilians in mass graves. Trimble’s team was assigned to excavate a representative fraction of those graves, with the goal of collecting enough evidence to convict Saddam Hussein of crimes against humanity in the new Iraqi courts.

The heat was overwhelming: 115 degrees. You felt as if your brain were boiling in your skull. Then there was the isolation. The desert seemed to stretch to the horizon in every direction, so that the cordoned-off rectangle of sand with its bulldozing equipment, the little American encampment with its white, igloo-like tents, stood out like a target.

Down on the scorching sand of the excavation site, Trimble and his team felt the precariousness of their position. Here they were, in the middle of a war zone, a bunch of Americans digging up graves. The wind “was blowing like hell,” but Trimble could still hear occasional pops of small-arms fire: “somebody trying to get through our lines.”

When Trimble had volunteered to go to Iraq, there were people in his field who said, “What the hell is Trimble up to this time?” Most archaeologists specialize, but Trimble was not like most archaeologists. He had determined early on that he “was not willing to spend 25 years toiling at the same dig.” He dreamed of a job diverse enough to keep him interested, a job that would use “every single skill I had.”

Fresh out of the Ph.D. program at the University of Missouri, he had audaciously proposed to the Army Corps of Engineers that it create a curatorial center of expertise to manage all its artifacts lying in storage; in 1991, the Corps obliged, and installed Trimble as its director. He soon developed a reputation as a maverick. He was ambitious, and he wasn’t afraid to take on jobs that he’d never done before. Time and again, Trimble made his way to the center of big, national projects: Kennewick Man, the African Burial Ground National Monument in Lower Manhattan, the loan of a rare T-Rex to the Smithsonian.

Trimble, who hailed from a family of Marines and had always wanted to serve his country, saw Iraq as a “once-in-a-generation” mission that would require all his strengths: assembling a team, motivating people in the field, managing logistics, designing and building systems on the ground. He was experienced in working at grave sites; given the choice in his career, he had always opted to work on skeletons over pottery. Even when the mission had been a weighty one, like helping the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command to recover the remains of American soldiers in Southeast Asia, he had never hesitated to volunteer.

Scenes from the Iraqi desert, 2005-2006: Trimble and his team excavate mass graves and catalogue evidence. (Photos courtesy U.S. Army Corps of Engineers/RCLO)

It was only after he got to Iraq that he understood how extreme the job would be. “The urgency was tremendous. The president wanted to try Saddam Hussein as soon as possible,” Trimble recalled. “But one of the first things they said to me was, ‘We have to have standards (for proving crimes against humanity) that exceed the standards of The Hague.’ ”

Despite the urgency, Trimble and his team spent most of their first week staring at sand. While U.S. soldiers secured the perimeter of the rectangular pit, a track hoe operator skimmed off sand. Trimble directed him, a few centimeters at a time. All eyes watched for a slight change in sand color: the telltale sign of corpses beneath.

Tedium is a part of any dig, but most digs are not in the middle of war zones. Trimble checked his watch every 10 minutes, painfully aware that each minute they spent in this exposed location risked everybody’s lives. “I was on people all the time to work more, work faster,” he told me. “I was obsessed by nobody on my team getting hurt. What was I going to say to their parents if they got killed doing forensic work on dead people?”

Trimble began to wonder if he were even digging in the right place. Then he saw it: the discolored sand. The team rushed to the pit, carefully removing the next layer with hand tools and brushes. What came next shocked even the old hands. Most soil in the world has acidity, which disintegrates clothes, but here in the desert, the team pulled a scrap of clothing from the earth. “That was a shock for me,” Trimble said. “To see bones inside of clothes.”

Trimble told the operator to make parallel passes with the track hoe to see how wide the grave might be. He knew that in a massacre, the victims would fall at angles. At the first sign of a foot or a head, Trimble called over the team members. Carefully they cleared away the last layer of sand. The dead lay tangled in stacks: women, children and babies in brilliant-colored traditional Kurdish clothes, most of them with gunshot wounds to the head. The babies’ thin skulls had shattered into tiny pieces.

"That was a shock for me. To see bones inside of clothes."

“I had never worked on graves where there were so many children,” Trimble told me. “You know, most archaeologists, after a while, they treat skeletons as bones, not people. But little kids with clothes on are little kids. That was very upsetting.”

One day there was a 2-year-old with a ball where his hand used to be. “I couldn’t go into that grave,” Trimble said. “Once they moved the ball I could go in, but before that …” His voice trailed off. “All objects bring back memories for us. Pacifiers just like the ones your children have used. You can see they’ve been murdered. You have to push that to the back of your mind.”

Trimble’s team pulled 123 people from the first grave site. All were women and children. The average age was 11 years old. The majority had been shot in the back of the head.

The team mapped, sketched and photographed the dead exactly as they were found, taking pains to gather every scrap of evidence. Then, as much out of compassion as duty, the team made a case file for each victim, to honor each life.

When the field analysis was completed, workers placed every victim’s remains into a body bag. As soldiers loaded the body bags into trucks, Trimble stood nearby, watching. “Treat these people well,” he said.

******

Along one of Washington’s power corridors, Sonny Trimble was hoofing it to a meeting with a VIP. He still wore the suit and tie, but now he carried a duffel bag — that telltale sign of his life in the field — which he needed to stash somewhere before his meeting. His cellphone rang: the theme song to “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.” With a sheepish grin, he switched it off.

Though Trimble has been based in St. Louis for 27 years, he gets the rhythms of Washington: the hiring cycles, the funding cycles, the fact that when you get five minutes with the top brass, you have to make it count. This savvy stems in part from being raised in a nearby suburb by Washington insiders. His father, a medical officer in the Public Health Service, designed and built health centers around the world in the 1950s and ’60s; his mother, a voracious reader, was a senior codebreaker at Arlington Hall during World War II.

After the war, Mrs. Trimble became a full-time mother, but “she let it be known that she was not going to sit in Virginia and be a housewife.” Mrs. Trimble told her husband to find a posting. If she was going to do something ordinary, she wanted to do it in an extraordinary way.

So the family moved to Ethiopia. Sonny grew up there in the 1950s, between the ages of 5 and 13, playing with the local kids, because his parents preferred not to be cooped up in the embassy compound. They lived in a series of old Italian villas on the edge of town, because his parents believed “we could only experience Ethiopia and the Ethiopians by living out amongst them.” Sonny learned about America from the Sears Roebuck and Co. catalog and U.S. News & World Report, and annual trips to visit his grandparents in Virginia.

Trimble in Iraq in 2005. (Photo courtesy U.S. Army Corps of Engineers/RCLO)

Watching his father build local clinics, he got his first lessons in “functional analysis” — the value of building relationships, and the necessity of working with the materials and resources you have, not the ones you wish you had. From his mother he got “this idea that you’ve got to get out and see the world and not be afraid of anything there — that it’s a great place, an interesting place.” Every summer Mrs. Trimble took the kids (and when he could spare the time, her husband) on “a grand tour of somewhere.” Once, in 1962, she booked passage in a spartan cabin on a French tramp steamer, The Vietnam, docking in Aden, Saigon, Mumbai, Sri Lanka, Singapore, Hong Kong and Yokohama. When Trimble arrived in Winston-Salem in the fall of 1970, he had to be the only Wake Forest undergraduate carrying around that particular set of stamps in his passport. His father initially urged him to study economics, but Trimble got interested in the new medium of television. “There was still the excitement of TV,” Trimble recalled, “that feeling of: What are we going to put on this device?” He spent a summer doing research for a local TV station, surveying people about what they wanted the station to program. The answer came back loud and clear: more movies. He gave his presentation for “the bigwigs,” who “threw me out of the room.” Within a year, Ted Turner was launching the first national all-movie channel. Trimble took it as vindication of his methods: “It taught me that over time, the data don’t lie. They will take you to a conclusion.”

Meanwhile, he had discovered anthropology. He took a course a semester, several of them from the young, charismatic Ned Woodall (P ’99). “His lectures were these electric performances. You never wanted to miss one,” Trimble recalled. “He would say, ‘This is the standard. I don’t grade on a curve. If you can’t hack it, tough.’ And if you had a lot of talent and you squandered that talent, he had the greatest scorn in the world for that.”

Trimble started working under Woodall at his digs in New Mexico and on the Yadkin River. “He was a taskmaster on the basics. I’m a pretty competitive person, so I liked it. He showed you that doing great archaeology was possible. And if you could raise the bar, you should.”

Trimble at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History with an Army Corps T-Rex. (Photo courtesy U.S. Army Corps of Engineers/RCLO)

Wake Forest was affecting Trimble in other ways, too. He began to think more about “doing good things — not just things that are for you. I had not thought about that before.” He was also working harder academically than he had ever worked in his life. When Woodall led a study-abroad trip to Venice, Trimble, who was not a straight-A student, didn’t expect to be chosen. When Woodall called and told him to pack his bags, he “almost started crying,” he was so moved by Woodall’s faith in him.

The Venice semester marked Trimble’s first time traveling as a young adult. It started off with a bang. Woodall, who was traveling with his wife and baby, invited Trimble and another student to come along to Yugoslavia in a Volkswagen bus with a broken taillight. Several hours later, Trimble was in the passenger seat when border guards with AK-47s approached the van, shouting at them to stop. He found himself sitting at the border station while Tito’s officials thumbed through his passport and the baby wailed.

One day during the Venice trip, Woodall finally made his pitch. “He said, ‘I think you can be good at this. It comes so naturally to you. What do you want to be: some guy in the basement of a TV station crunching numbers? Or you could be working outside, discovering something important about the prehistory of this country. Which would you rather do?’ ”

******

At Arlington National Cemetery, even the sunny days feel somber. One day last July, Trimble was making his way along the paths in 95-degree heat. “That’s section 60,” he said. “That’s where a lot of the Iraq and Afghanistan veterans are being buried now.” A woman knelt near a grave, crying. “That’s the saddest part of the cemetery right now.”

"If a piece of history can be salvaged, it ought to be."

At a storage facility, Trimble unlocked a giant wooden gate and yanked hard. The door swung open, revealing an overgrown yard. His eyes bluntly took the measure of the scene before him: a hundred enormous carved stones on pallets, their white paint flaking in the sun. Few except Trimble would have known what they were: the disassembled pieces of the columns of the 1818 United States War Department building. “These are really beautiful pieces of American history,” he said.

Trimble climbed with alacrity from stone to stone, pointing out their features. It was as though he were catching up with some old friends. “See here?” he called out. “They lined the inscriptions with lead. And right there — that’s where the stonemasons carved their names.”

Trimble at Arlington National Cemetery with the disassembled pieces of the former Ord-Weitzel and Sheridan gates. The restoration is scheduled to be completed in 2017.

After the Civil War the columns had traveled from the old War Department to Arlington Cemetery, where they became the Ord-Weitzel and Sheridan gates to the cemetery in 1879. In 1971 they were pulled down to widen the road and abandoned in a grove of trees. They were still languishing there two years ago when Trimble got the call to come and restore them. I asked him why he was doing it. He looked surprised. “If a piece of history can be salvaged, it ought to be,” he said.

Out in the sun, wearing his baseball cap and khakis, Trimble began relating the story of how he had moved several five-ton stones out of the woods last year. A couple of trees were in the way, so he first had to beg the Arlington arborist to cut them down. “Then we had to get a 60-ton crane,” Trimble said, grinning. “I was in heaven.”

On the way out of the cemetery Trimble noticed an impeccable group of uniformed soldiers walking down the paths: the U.S. Army Old Guard. “Look at that,” he said. “Those guys are in full wool suits, and I’m complaining about being hot.” He stared out the car window as he passed the gravestones, row upon row upon row. He said, “I feel in debt to those guys forever.”

******

Trimble’s hair went gray during his first year in Iraq. On his fourth day in the Green Zone, a rocket knocked him to the ground in the middle of a meeting; it killed two people. Soon afterward, Trimble was at his work site, waiting for an approaching convoy, when one of the trucks hit a landmine and exploded. Trimble and a Marine Corps major ran toward the flames. “The two drivers were alive. It was one of the happiest moments of my life,” Trimble recalled. “I held this one guy for half an hour. He was shaking and crying.”

Trimble became obsessed with protecting his team. At first, his trucks had no armor. Traveling the same 18-kilometer stretch of road every day to the work site, he kept thinking, “How can I get our people out of this place alive?”

On the next dig, he made up his mind to do it differently. “I told the guys in Baghdad, ‘I want to live on site, 200 meters from the bodies.’ ” Baghdad obliged, guarding the new dig and its encampment with 60 full-time private security guards.

Trimble had yearned for a job that would use every skill he had, and here it was: “functional analysis” at its most intense. As is his wont, Trimble hired people he could lead but wouldn’t have to micromanage, and created systems to help them do their best work. To minimize the number of people he exposed to danger, he gradually replaced some of the experts with people he could train to do multiple tasks; the team shrunk from 30 to 19.

Because working in a field lab 200 miles from Baghdad was both less safe and less efficient, Trimble persuaded his bosses to build a state-of-the-art forensics lab in Baghdad. A senior official agreed to let him use two Black Hawk helicopters (“the taxicabs of the war”) to ferry body bags back to the lab in Baghdad. In all, the team would excavate 301 Kurds and Shiites from three crucial grave sites, and photograph dozens of other mass graves to hint at the scope of the massacres. Trimble’s final report, a masterpiece of its kind, showed evidence that Saddam had committed crimes against humanity in crystal-clear, incontrovertible detail. If you have a chance to raise the bar, you should.

Among the graves of servicemen and women at Arlington National Cemetery. “I feel in debt to those guys forever,” Trimble said.

But the danger and the horror of the job gnawed at Trimble and his team. An IED went off 9 miles from his dig. His team went through an entire case of Duco Cement while gluing skulls back together. “We had to replace some people because it’s almost like their heart couldn’t take it any more,” Trimble said. “Who knows how it builds up inside of you? It’s like being slowly sanded with sandpaper.”

One day one of the government lawyers told him, “They’re going to want to put you on the stand.” Initially, Trimble wasn’t interested in testifying. “Then I realized, there’s no way I’m letting someone else represent our team,” Trimble said. “The guys that did the work are going to give the testimony.”

So it was that Trimble, his “heart beating really fast,” found himself on the witness stand in a courtroom of the new Iraqi government in April 2008, facing Saddam Hussein himself.

Trimble gave five and a half hours of testimony. All over the Middle East, shops closed, and people watched Trimble’s testimony as it was broadcast live. Carefully, methodically, he described the massacres: how the killers herded their victims into the pits, the firing methods, the weapons. He described how ballistic evidence showed that killers shot some of the victims in the legs first, so that they couldn’t run. He talked about how the killers chose remote desert sites, hidden by hills, so that locals wouldn’t see them.

Saddam Hussein, representing himself, rose to cross-examine the witness. He began by attacking Trimble’s credibility, arguing that an expert “from the army of the enemy” couldn’t be trusted to tell the truth.

The Iraqi court disagreed. Due in large part to the evidence collected and presented by Trimble’s team, Saddam Hussein was convicted of crimes against humanity.

******

Trimble had one more stop to make in Washington. He was at the Smithsonian (“I used to dream about working here”) to check in with the paleontologists who were preparing a Corps-owned Tyrannosaurus Rex for exhibition. Walking into a room filled with crates and scientists, he was immediately at home. He made a beeline for the bones.

Trimble with special crates designed to protect the bones of a rare Army Corps of Engineers-owned T-Rex: The Smthsonian’s highly anticipated exhibit opening in 2019.

Watching him in the dinosaur room, you could not help but feel glad that, after all those horrific days in the desert, he was now working on something guaranteed to make schoolchildren squeal with delight. From here he was headed home to St. Louis, then on to Governors Island off New York City, where he had been asked to relocate a Civil War military cemetery. “If a grave has to be disturbed,” he said, “you want the right people doing it.”

Anthropology is the study of human beings. Sonny Trimble is a civilian who works well with the military; an academic who is at home among track hoes and cranes. He studies the dead, but he also develops the potential of the living. He thinks if you can raise the bar, you should. And he is a big believer that if a guy wants to learn something, he’d better do it himself.

Joy Goodwin (’95), a journalist and screenwriter, is currently adapting a collection of true stories from the Underground Railroad for television. She teaches creative writing at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.