Cathe O’Connor Dykstra (’84) says that when you ask children of participants in the Family Scholar House program to tell you their age, most will politely do so. And they’ll also tell you the year they’ll graduate from college. Dykstra, CEO for the Louisville, Kentucky-based community service initiative, says that’s because from the moment families are accepted into the program, the focus is on education: acquiring it, using it, continuing it and preparing the little ones for it.

Cathe Dykstra (left) with Maria Patterson, University of Louisville Class of 2012 graduate.

Family Scholar House (FSH) is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to end the cycle of poverty and transform the community by empowering families and youth to succeed in education and achieve lifelong self-sufficiency, says Dykstra, who describes herself as the “chief possibility officer” of the organization that offers both non-residential and residential programs. “We want to empower instead of enable. We don’t do it for the accolades,” adds Dykstra, who described seeing a young woman come in, holding the hands of her children, with no place to sleep. “We do it because when the next generation is better off, the community is better off. Funds that would have been used to keep her in poverty have been freed up for someone else because she’s independent.”

Dykstra, an economics major who grew up involved in community service through her church in Columbia, South Carolina, said Wake Forest was a different introduction to servant leadership. “How do we leave the world a better place than we found it? How does what we do affect us but also others? After I left Wake Forest I quickly found myself called upon to nonprofit work that helped people.”

Ananecia Williams, Class of 2012, and Jayler, Class of 2028

She worked with senior citizens trying to stay in their homes and as a parent educator at her daughter’s school. Then, after moving to Louisville, she interviewed for a job at what was then known as Project Women, a small transitional program focused on education. From her experience running an economic success program in a domestic violence shelter she saw an opportunity to expand the mission and take it to scale. There were four people in the program, and four staff members, in a program that began by housing one single mother and her child.

During the interview Dykstra found herself doing a cost-benefit analysis in her head. “They described for me a vision that at full potential they would serve 12 people,” she said, “providing parental support, helping them get an education to become financially self-sufficient and raise their children into a whole new life. I could have listed 200 people; I knew there was such a great need.”

She accepted the job with Project Women, which eventually became Family Scholar House. In its first 19 years the program has seen a significant increase in the number of single parents, male and female, seeking assistance while expressing the desire and motivation to enter or continue their post-secondary education. Participants enroll in the colleges of their choice to pursue the courses of study of their choice, with the goal to obtain a baccalaureate degree. Family Scholar House helps single parents obtain financial assistance to pay for classes and books. Through individual donations, financial aid, Pell grants, scholarships and sometimes student loans, participants attend school on a full-time basis. Some of the parents also obtain work-study assistance through their colleges or universities. All participants meet regularly with their academic advisor to review educational progress.

In 2008 FSH opened a 56-apartment campus, Louisville Scholar House, providing participants and their children housing and educational support. The second campus, Downtown Scholar House, opened in 2011, followed by Stoddard Johnston Scholar House in 2012 and Parkland Scholar House in 2013. While federal low-income housing tax credits have assisted in building the campuses, no federal dollars are provided for programs and services, said Dykstra, who now has a fulltime staff of 12 along with 1,500 volunteers. “Eight percent of our budget is from the United Way, and the rest is donations and grants.”

In 2008 FSH opened a 56-apartment campus, Louisville Scholar House, providing participants and their children housing and educational support. The second campus, Downtown Scholar House, opened in 2011, followed by Stoddard Johnston Scholar House in 2012 and Parkland Scholar House in 2013. While federal low-income housing tax credits have assisted in building the campuses, no federal dollars are provided for programs and services, said Dykstra, who now has a fulltime staff of 12 along with 1,500 volunteers. “Eight percent of our budget is from the United Way, and the rest is donations and grants.”

Since 2008 nearly 400 families — with more than 500 children — have lived in the residential program. Ninety-five percent of these single parents have experienced domestic violence, said Dykstra, and an alarmingly high percentage of their children have witnessed someone hurting their mom.

More than 900 families are in the pre-residential program receiving services including academic advising, toddler book club, peer support, diapers and transportation passes while waiting for housing to become available. About 98 percent of residential clients did not have a subsequent pregnancy during their participation at FSH, and there is a 93 percent completion rate for college credit hours attempted by participants. Sixty-one percent of participants have continued their post-secondary education after exiting the program, many in graduate programs. In its first 10 years (prior to Dykstra’s arrival) two participants received their college degree. That number stands at 186, with 53 more graduating May 18.

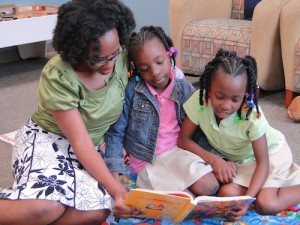

Keneysha Rodney class of 2011, Kennadi, Class of 2023 and Nadia, Class of 2025

Top fields pursued by FSH graduates include nursing, social work, special education and justice administration, said Dykstra. Four hours of service is required each month as a thank-you to the community that supports them, and that often leads to residents’ having a direction for their community, said Dykstra. “It happened to me. I saw needs and I had some skills to help. From that a career was born. I didn’t want my daughter to believe she was what she did. We are each so much more than our work.”

Within 90 days of exiting the program 70 percent of participants are off government assistance and raising their own children in a college-going culture, she says. “I know how high the bar will be set for them because their parents went to college. All the children know the year they will graduate from college.”

The impact of Family Scholar House became even more personal for Dykstra when her husband was diagnosed with cancer. “We’ve had nurses at every hospital who were either graduates of Family Scholar House or living there,” she says. “They cared for him like he was family because he is.”

“I remember them coming in with babies in their arms, unemployed, and now we see them capable, competent and compassionate,” she adds. “It’s wonderful to come full-circle and see the difference we make on micro and macro levels in the community. I’m blessed to know I had a small part in a big difference in the lives of really phenomenal people who would not have succeeded without help.”