(This story was originally published in 2015.)

For several years before a fire heavily damaged what is today Graylyn International Conference Center, the 1930s Norman Revival-style mansion was a women’s dormitory. From 1977 until the devastating fire in 1980, about 40 students a year lived in what had once been the Bowman Gray family’s opulent bedrooms and guest rooms or in modern apartments over the swimming pool and garage.

It was far from today’s luxurious conference center, but vestiges of the house’s grand past remained, from a circular iron staircase topped by a beehive-shaped ceiling, to a beautiful, if empty, indoor swimming pool with art deco tiles and hand-painted murals. Students lived in rooms with fireplaces, oak paneling, slate floors, leaded windows, original wallpaper and marble bathrooms with hand-painted tiles and 17-head showers.

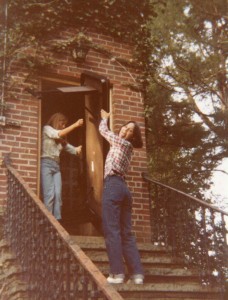

Sallie Adkins Schurmeier (’79) and Cissy Kelton Byrd (’79, P ’06) carry furniture into the entrance to the Graylyn pool apartment in 1978. (Photo courtesy of Kate Murray)

“I loved the opulence of the mansion and just imagining the history behind it; it felt like an adventure and a dream world living there,” recalled Karen Kindle (’79), who lived there for two years. Kindle is now an administrative analyst with the New Jersey Division of Gaming Enforcement.

Carla Damron (’79) and two roommates shared a large, wood-paneled master bedroom on the sprawling second floor. How could you not appreciate living in a “giant stone masterpiece,” said Damron, who today is executive director of the South Carolina National Association of Social Workers. “It was an amazing experience for a poor scholarship kid to stay in such a magnificent place.”

Did you live at Graylyn? Send your story to kingkm@wfu.

Graylyn was built by Bowman Gray Sr., chairman of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. Gray lived in the house for only a few years before dying in 1935. In 1946, the Gray family donated the estate to the Bowman Gray School of Medicine. The medical school used the house as a psychiatric hospital and, later, as a school for children with special needs.

In 1972, Bowman Gray’s son Gordon purchased the estate from the medical school and donated it to the University. Throughout the ’70s, the estate hosted fraternity and alumni parties and other events. The Mews stables complex was renovated to house law students, and several cottages were used for foreign-language houses.

The manor house was once home to Professor Emeritus of History Jim Barefield, who lived in the butler’s apartment over the garage from 1965 to 1975. The house had a “gloomy, medieval look” back then, he said, a perfect setting for the history honors courses he taught in the apartment.

At night, he used candles to explore the tunnels under the house. Then-Provost Edwin G. Wilson (’43) and then-Dean of the College Tom Mullen sometimes joined him for the late-night candle tours. Mullen remembers how much his children, Eric (’88, MD ’99) and Renee (’85), also enjoyed exploring the house, especially the attic. “They were convinced that Maleficent was up there somewhere,” he said.

Graylyn, circa 1979. (Photo courtesy of Kate Murray)

Rebecca Johnson Melvin (’79) lived in three different places on the Graylyn estate: in the manor house; in the stone tower in the Mews complex; and in Bernard Cottage, when it was used as the French house.

She lived in the manor house in a large suite that had been subdivided into two bedrooms, with a luxurious bathroom and a balcony. “The house was extraordinary, exquisite,” she recalled. “Most of the original furniture was removed from the ‘dorm’ rooms, of course, but the architectural details provided all the atmosphere that you could imagine.” Her resident adviser’s room “had a four-poster bed, a private bath and French silk wallpaper; delicate, beautiful – we were in awe of that room.”

Students were supposed to stay on the second floor, but it was too tempting not to explore the rest of the house. “On occasion, we were able to go down that main staircase to the first floor, which was like a spooky haunted house because no one lived there,” said Melvin, head of the manuscripts and archives department at the University of Delaware Library. “It wasn’t totally empty, but it was deserted and quiet with lights off.”

Karen Beasley Raliski (’80) greets James Bryan May in her room at Graylyn. (Photo courtesy of Karen Raliski)

Karen Beasley Raliski (’80, P ’07, ’13) lived in a guest bedroom on the second floor her sophomore year. “Graylyn was a great place to call ‘home,’ ” she said. Thirty years later, her daughter, Kristen Fyock (’07, MSA ’08), stayed in the same room when she got married at Graylyn in 2009.

As a student, Raliski shared the room with three other women. “We liked to show off the marble fireplace and marble bathtub in our private bath. The room had two sets of bunk beds and four separate desks,” she recalled. “With four girls and one tiny closet, we needed more storage, so we appealed to Dean (of Women) (Lu) Leake, and she agreed for us to go to Sears and purchase a cardboard wardrobe.”

Like other students who lived there, Raliski couldn’t resist exploring the large formal rooms on the first floor. “Some furnishings were left in the library, so I remember sneaking in there from time to time as a quiet place to study. The grand spiral staircase was also a neat place to go, from bottom to top and back.” Today, Raliski is career development coordinator at Pinecrest High School in Southern Pines, North Carolina.

Linda Patterson Morris (’79) and Karen Kindle (’79) in the pool apartment kitchen. (Photo courtesy of Kate Murray)

Students also lived in a modern apartment with three bedrooms, a living room and kitchen above the empty indoor pool. “It was so unique,” recalled Kate Murray (’79). “I had been in dorms my first two years, and it was a super opportunity.”

Murray, now special events coordinator for the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum in Ann Arbor, Michigan, still has a stack of snapshots showing students enjoying meals together and hanging out in the pool apartment. “There was a sense of closeness that you didn’t get in the dormitory,” she said.

In fall 1979, the pool apartment became the German House for male students. David Ross (’82) recalls epic card games and dinners with German department faculty members in the apartment and the “German House 500,” an indoor bike race. Riders were timed to see who could ride the fastest from one end of the house to the other.

Dinner in the pool apartment in 1978 (clockwise from left): Karen Kindle (’79), Kate Murray (’79), Sallie Adkins Schurmeier (’79), Mary Canniff-Kuhn (’79), Cissy Kelton Byrd (’79, P ’06) and Linda Patterson Morris (’79). (Photo courtesy of Kate Murray)

During the summer of 1980, Graylyn’s third floor was being renovated to accommodate even more students. On June 22, a fire broke out on the third floor while 7,000 people attended a Winston-Salem Symphony concert on the grounds. The fire gutted the third floor and caused extensive smoke and water damage to the rest of the house. (Arson was suspected, but no one was ever charged.) The next day, President James Ralph Scales promised that the house would be rebuilt.

About 60 students had planned to live at Graylyn that year. They were reassigned to cottages on the estate grounds, to the faculty apartments or to dormitories on campus. Eight male students were allowed to stay in the largely undamaged pool apartment for another year while the house was being renovated.

John Korzen (’81, JD ’91), now an associate professor at the Wake Forest School of Law, lived in the pool apartment the year before and the year after the fire. He had a front-row seat to the renovations. “I still remember every morning at 8, workers would start hammering and doing work on the house,” he said.

Graylyn reopened as a conference center in 1984.

The Graylyn fire on June 22, 1980