After hearing from alumni with their generous suggestions and seeking advice from the campus community, Wake Forest Magazine curated this random collection of objects, from the whimsical to the serious and the historic to the fleeting (dress codes, anyone?). This assemblage humbly offers a few answers — but by no means a complete list — to an endless inquiry: What things make Mother so dear, not to mention fascinating?

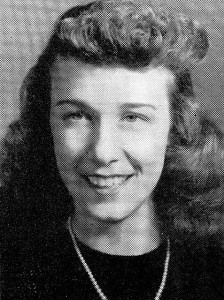

F-WAC’S GUIDE FOR FRESHMAN WOMEN

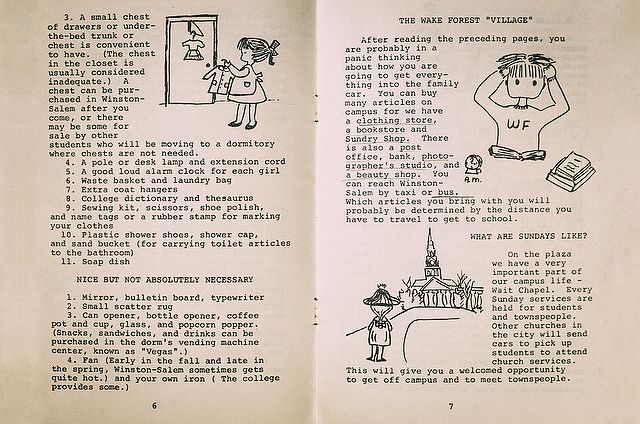

Whereas a 1960s freshman handbook for men stresses balancing academics and extracurricular activities, the equivalent for women begins by covering “just about all the ‘girl-type’ problems that arise when you go off to college,” such as leaving your formals at home (they can be mailed when you need them), or when to start wearing cottons again (right after spring vacation).

“Happiness is Being a Deacon Coed,” distributed by the Freshman Women’s Advisory Council (affectionately called F-WAC), offers tips on storing clothes (“We find blouse racks are more trouble than they’re worth”) and dorm room accoutrements that are “nice but not absolutely necessary” such as popcorn poppers, mirrors and small scatter rugs.

Believe it or not, Wake Forest was not all work back then. Coeds were encouraged to bring knitting or a musical instrument. Friendliness was a tradition, and getting along with your “roomie” took patience and compromise. “Your boyfriend may be the most important person in the world; that is, except for hers!”

All the girl-type problems addressed, the booklet introduces women to the most important and exciting part of the year at Wake: academics. “There will have to be an adjustment when you discover that there are a lot of people with a lot of intelligence,” it cautions, reassuring that competition encourages everyone to work to their potential.

Coping tips? Create a study schedule. Get enough sleep or you may end up another mono statistic. Turn to your faculty advisers for help. And look forward to the holiday season, when coeds string popcorn for the dorm Christmas trees, even persuading their dates to take needle and popcorn in hand.

THE PILOT’S (ZSR) FLYING GOGGLES

Before his death at age 21, Zachary Smith Reynolds, the youngest son of R.J. and Katharine Smith Reynolds, distinguished himself as a competent aviator. In 1931 the dashing, dark-haired pilot flew a record-breaking 10,000-mile trip around the world in the open cockpit of his single-engine biplane flying boat, designed by Savoia-Marchetti and customized with a single seat and extra fuel capacity. Smith was just 20 at the time of his daring flight over Europe, North Africa and Asia.

In the Collection Archives of his former family home, now Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Smith’s flying goggles and case allow visitors to visualize him in his heyday, boarding his aircraft for the next leg of the journey. The goggles, manufactured by American Optical and made of glass, elastic, metal and rubber, sustained heat damage when stored in an attic but still represent a significant connection to Smith’s flying history. Folllowing his death on July 6, 1932, the Reynolds’ siblings established a trust in their brother’s name that provided for his namesake foundation, the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation. As a result, Z. Smith Reynolds Library at Wake Forest is named in his honor, as is Winston-Salem’s Z. Smith Reynolds Airport. The goggles and case were a gift to Reynolda House from Lloyd “Jock” Tate, president of the ZSR Foundation, and his wife, Kathryn.

MEIKLEJOHN AWARD

Wake Foresters hold dear their individual symbols of pride: Wait Chapel, the Demon Deacon, diplomas, the seal. But stored in the Z. Smith Reynolds Library’s archives is perhaps one of the greatest symbols of institutional pride — one that many may have never seen nor heard of: a plaque representing The Alexander Meiklejohn Award for Academic Freedom. Presented to the University in 1978 by the American Association of University Professors, the award recognized the resolve and courage of President James Ralph Scales, the Board of Trustees and the faculty while honoring the ultimate testament to a university’s character: its resolve to uphold its core values.

An underlying friction between academic freedom and religious orthodoxy was always present in the governing relationship between Wake Forest and the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina, but in 1977 two specific incidents came to symbolize the widening gap.

In February, Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt spoke on campus at the invitation of the Men’s Residence Council; he received the “Man of the Year” award for his entrepreneurial skills and fight for First Amendment Rights. His visit provoked a storm of protest among Baptists, but President Scales said his appearance was allowed under the University’s “open platform” policy. Some Convention leaders believed the Flynt incident illustrated the University’s increasing lack of concern for Christian ethics and an increasingly secular view of life.

Later the same year, a dispute between the University and the Convention related to federal involvement — what some Convention members described as intrusion — in higher education arose over a grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to support undergraduate science programs. The University intended to apply a portion of the grant toward construction of a biology department greenhouse/animal facility behind Winston Hall. The Convention instructed the University to use the funds for some other purpose, saying it must be spent according to Convention guidelines for services rendered — and those guidelines did not include bricks and mortar. The trustees refused to follow the instructions, and, in what was described as a “very decisive vote,” announced their intention to honor the good-faith agreement with NSF.

The greenhouse facility was ultimately built using other University funds. But the ensuing controversy related to the Flynt and NSF incidents kindled a movement, led by President Scales with support from the trustees, that resulted in the adoption of a new covenant relationship between the Baptist State Convention and the University.

James Mason (JD ’38, LL.D. ’96, P ’67), then chair of the Wake Forest Board of Trustees, recalled the board’s decision to seize upon the issue of the biology grant and draw a line. Withstanding calls for their dismissal, the trustees weathered criticism and disapproval. At a meeting of the Convention’s General Board, President Scales and Mason stood their ground; their determination led to a meeting of the trustees and the General Board in March 1978 on campus. Addressing both bodies at a dinner meeting, Mason said it was time to acknowledge that the University was entitled to new freedoms.

The Board was determined not to sacrifice 144 years of freedom which the University had enjoyed.

Mason remembered this meeting as one of the high points of his chairmanship, wrote Mike Riley (’81), assistant editor of the Old Gold & Black, who interviewed Mason in November 1979. “In this significant meeting, the issue of control and the trustees’ legal position was made public,” said Mason. “At this point, the trustees adopted a position of acting, not reacting.”

“I think it is fair to state that the debate over federal funds was not the issue,” Mason told the OG&B, adding that control of the University was at stake and the trustees embarked on a determined course to effect a new relationship between the University and the Convention.

In 1978 the University received the Meiklejohn Award in recognition of its defiance of the Convention. The board was determined not to sacrifice 144 years of freedom which the University had enjoyed, said Mason, recalling that, “It was a right high moment for me to go to Yale University and receive the award on behalf of the trustees.”

“We were confronted with two problems,” he said in response to the award, for which the University was nominated by Professor of English Doyle Fosso, president of the University Senate at the time. “The answers would affect the basic personality of the University. There was the usual anguish as we sought compromises that would placate a host of antagonisms suddenly crowded into our academic amphitheater,” Mason said. “After that understandable detour, we stopped fooling ourselves and said that the open platform shall remain open and that the Board of Trustees shall remain the final arbiter in decisions affecting the life of the University.”

Provost Emeritus Edwin G. Wilson (’43) describes President Scales as the “white knight” whose vision and leadership guided Wake Forest through a challenging and historic period. Acknowledging the award for academic freedom, Scales declared the University would remain “a fortress of independent thought.”

When Scales announced his resignation in 1983, he said his most-valued memory was the Meiklejohn Award. “The hospitality Wake Forest shows to new ideas doesn’t mean we’re not tough-minded and don’t have convictions,” he told the Old Gold & Black. “I have worked hard to preserve freedom for views I may despise,” he said, adding that such freedom was essential in the marketplace of ideas.

********************************

IN HINDSIGHT

“When you’re 20 you do things that when you’re 60, you hope don’t come back to haunt you,” says Angelo-Gene “A.G.” Monaco (’77). In his case, the thing he did as a Wake Forest senior might well have haunted him. Instead, it taught him life lessons and a profound respect for his alma mater.

Monaco was chair of the Men’s Residence Council (MRC) in fall 1976 when he extended, on behalf of the organization and absent the blessing of the administration, an invitation to Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt to speak on campus. “We wanted to make a splash, so to speak, and we didn’t have the Vietnam War to protest, Watergate was over,” he says. “We decided to try to get somebody famous for the Man of the Year award — somebody off the beaten path.”

MRC members voted on candidates and Flynt finished second to Uganda President Idi Amin. They found the despot difficult to contact so they moved on to Flynt, finding his mailing address inside a copy of Hustler and proceeding full speed ahead. “We were just a bunch of smart-ass kids trying to pull something off,” Monaco says.

What began as something of a prank with less than noble intentions quickly escalated when Flynt surprisingly accepted the group’s invitation. His scheduled appearance in February 1977 drew ire from the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina, with which Wake Forest shared an already strained governance relationship, as well as countless other callers and letter-writers. But the University stood its ground and stood by its students, says Monaco, with President James Ralph Scales championing the cause for free speech.

By the time Flynt arrived on campus he had been indicted on obscenity charges in Ohio and had gone from pornographer to what Monaco calls the “poster boy” for First Amendment rights. He spoke to a crowd, Monaco says, including many law students who had him autograph their First Amendment textbooks and several women students who turned their backs on him as he talked. Flynt received the Man of the Year Award at the same event where the MRC presented the Rev. Coy Privette (’55, P ’81, ’83, ’87, ’89), Baptist minister and conservative activist, with the Alumni of the Year Award. “Obviously, we were looking to spark some discussion,” Monaco says.

Flynt’s invitation and appearance were decried by many, says Monaco, recalling that he was “dressed down” by Dean of Women Lu Leake and given the “opportunity” to respond to some of those angry letters. “She was a genuinely good person and, in hindsight, a terrific educator, but I was never close to being one of her favorites.” As it turns out Monaco is an associate vice president at Louisiana State University — Dean Leake’s alma mater. “Whenever a student at LSU gives me a hard time, I cannot help but believe Dean Leake is getting a little revenge.”

More than the impulsive decisions of young men, or their unforeseen consequences, what sticks in Monaco’s memory as he looks back are the words of Dean of Men Mark Reece (’49, P ’77, ’81, ’85). After the young student lashed out to the administration about freedom of speech, Reece told him firmly, “At Wake Forest we are not of afraid of (inviting) people we disagree with, but we expect you to be polite when you set it up.” These were old-school educators, says Monaco, and everything was a teachable moment. “If I learned anything I learned I wasn’t smarter than those people. I received an outstanding education, but they also taught me to put a napkin on my lap.”

With master’s and doctoral degrees in business administration, Monaco’s career has included managing labor relations at the Bronx Zoo and holding administrative positions at several universities. He reflects often upon the strength and poise of President Scales, whom he describes as the consummate college president. “He looked like a president; he acted like one. He stood by me when I was not the belle of the ball. As an administrator I’m not sure I would go the length he did to defend a wise guy like me. He gave me an amazing respect for my alma mater.”

As for Wake Forest history, Monaco’s take is that “a prank by a bunch of silly kids” didn’t change it, but leadership’s response did. “For the University it was a big deal but it was the character of the administration that made history. They held to this idea that you could speak about and challenge things, and they were going to defend it. They couldn’t be shaken,” he says. “When it came to freedom of speech they didn’t have to support us — we didn’t deserve it — but they didn’t back down.”

WAKE FOREST’S FREIGHTER

Photo Courtesy Wake Forest Historical Museum

Long before Wake Forest bought its houses across the pond, the University made its presence known internationally in World War II with a cargo vessel christened the SS Wake Forest Victory.

Victory class ships were mass-produced and transported goods and ammunition to troops overseas. Built with all the determination and efficiency of the typical Wake Forest student, the Wake Forest Victory made it from keel to completion in a record-breaking 27 days, launching from Richmond, California, on March 31, 1945. It could outrun a German U-boat.

Like most Victory class ships, the SS Wake Forest Victory was named after a place in hopes that people would support the ship that represented their town or institution. Students, faculty and staff were eager to help “their” ship and donated about 40 books for the ship’s library, including George W. Paschal’s three-volume “History of Wake Forest College.”

While the crewmen greatly appreciated book donations, literature alone couldn’t keep them entertained for long. By the second voyage, crewmen were begging for pin-ups of Wake Forest’s most beautiful women. “Our quarters are ample, our recreational gear is abundant, and yet one most decisive element is lacking: like all fighting units, we necessitate our charming feminine mascot,” said a letter from the gun crew quoted in the Nov. 2, 1945, issue of the Old Gold & Black. “And who could more readily exemplify the SS Wake Forest Victory than one of your own students?”

Women on campus dutifully posed for pictures while the campus voted — a penny a vote — on which photos were most worthy of being sent out to sea.

Crowned “Miss Wake Forest Victory” was the late Ruth Blount Fentress (’46) of Salisbury. The 1946 Howler noted that her pin-up, “along with photographs of fifteen other co-eds, was rushed to seamen.”

The Wake Forest Victory went on to serve in the Korean War and finally came to rest in New Orleans, where Hurricane Betsy damaged it beyond repair in 1965. The remains of the ship were later sold for scrap metal. The ship’s legacy lives on, though, in the form of a flag flown during its time in Korea, kept in the depths of the Z. Smith Reynolds Library archives.

A COMMEMORATIVE LOVEFEAST KIT

Could a simple box capture the same joy and light present in Wait Chapel during Lovefeast? The University decided to give it a try with a Lovefeast kit produced to mark the ceremony’s 50th anniversary. Each kit allowed those away from Wake Forest to replicate the Lovefeast experience with Moravian bun mix, Lovefeast blend coffee and beeswax candles. Alumni from Texas to Canada to Uganda rushed to order 300 kits.

As students filed into Wait Chapel on Dec. 7, 2014, Wake Foresters abroad and around the country tuned in to the Lovefeast livestream with kits in hand. Once all the candles were burning bright, it didn’t matter if people were in the chapel or watching from home. They doubtless felt the joy that came from breaking bread and sharing their light.

UNIVERSITY MACE

When James Ralph Scales was inaugurated as Wake Forest’s 11th president in 1968, biology professor John E. Davis led the faculty procession into Wait Chapel carrying something new: the University mace. Thomas H. Davis Sr. (LL.D. ’84) donated it in honor of his father, Egbert L. Davis Sr. (LL.B. 1904, P ’33).

“The handsome staff”— made of spun silver covered with gold plating and topped by a double-cast seal of the University — is “decorated with scenes and symbols of the University,” the Old Gold & Black reported. Etchings of Wait Chapel, Reynolda Hall, the cupola of the Z. Smith Reynolds Library and an arch are on the largest, middle section. Drawings of the Old Campus are on the top section. Panoramas of the medical school, Carswell Hall (the site of the law school at the time) and the skyline of Winston-Salem are on the bottom section.

The mace has since become a prominent symbol at Commencement, Convocations and the occasional Presidential Inauguration. For something with such a rich history, you’d think it would be suitably displayed. But to protect the silver finish, it’s covered in Bubble Wrap and stored in Reynolda Hall.

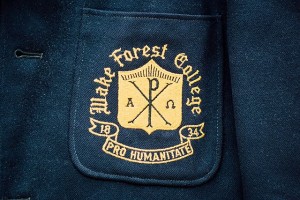

ED CHRISTMAN’S BLAZER

Greeting you on the Quad with that loud, boisterous voice-of-God voice — “Hello, Brother!” “Hello, Sister!” — the late Ed Christman (’50, JD ’53, P ’84) made you feel like you belonged at Wake Forest. Reverent and irreverent, prayerful and playful, wise and witty, he transcended the role of University Chaplain that he fulfilled so faithfully from 1969 to 2003. Even in retirement, he and his wife, Jean (’51), could still be seen strolling the Quad.  He proudly wore this black blazer — with Wake Forest College and Pro Humanitate embroidered on the pocket and the Wake Forest College seal on the buttons — still calling us to live the ideals of Pro Humanitate.

He proudly wore this black blazer — with Wake Forest College and Pro Humanitate embroidered on the pocket and the Wake Forest College seal on the buttons — still calling us to live the ideals of Pro Humanitate.

BELOVED BOBBLEHEAD SKIP

Skip Prosser made Wake Forest basketball exciting again. With the roar of the motorcycle, the flashing lights, the pulsating music, the sea of students in tie-dyed shirts, he rocked the Joel. With his wry sense of humor, his witticisms that drew from world history and English literature, and the unbridled joy with which this coach embraced life, he left us marveling at what a force he was. He left us too early when he died on that bleak July day eight years ago. But the thought of him still brings a smile. And with the 2008 bobblehead doll secure in the ZSR Library, Skip smiles back.

‘CHAPEAU OF SHAME’

Somehow everyone seems to recognize a freshman. Maybe it’s the naïve enthusiasm, the pristine pencil pouch or the nervous giggles at lunch-table gatherings. But in 1910 Wake Forest freshmen had to endure the original “wardrobe malfunction,” one that drove attention to their newbie status like a flashing “kick me” sign. They were commanded to wear the freshman beanie. Or was it a “chapeau of shame?” Back then it was a mandatory accessory for students such as James Graham, Class of 1914, whose black and gold felt beanie is among treasured objects at the Wake Forest Historical Museum. To make things worse, says Museum Director Ed Morris (P ’04), he’s seen photos of the beanies festooned with propellers. “I don’t know if they wore them all year, but certainly the first few weeks of school … so they’d be recognized on campus.” For all the right reasons, no doubt!

MEN’S SWIMMING TEAM SPEEDO & T-SHIRT, 1980

Tom Laraway (’80) of Avon Lake, Ohio, was a member of the men’s swimming team who competed in 1980 at Wake Forest’s last ACC championship appearance. In those days the University struggled to address Title IX compliance issues. As the fifth volume of Wake Forest’s history reports, that situation led, in part, to then-Director of Athletics Gene Hooks’ (’50, P ‘81) decision to eliminate men’s swimming as an intercollegiate activity.

As the years passed, Laraway kept his Speedo from the ACC meet, his T-shirt and memories of Coach Leo Ellison (P ’77, ’83). He was “very tough on the outside, huge heart on the inside,” says Laraway, adding that for Ellison college came first. “He had very high expectations for all his swimmers and often told us to ‘suck it up.’ My first semester at Wake he had me take 20 credit hours and swim twice a day. I learned very early (that) failure was not an option, and the way to get out of tough situations was to work your way out of them.”

Ellison died last year. Laraway is a senior business development director of BI Worldwide and remains in touch with teammates. On some days they swam up to 10 miles together. “We were proud to represent Wake Forest in the pool. We would like to see the pool named in honor of Leo Ellison,” he says. He is donating his swim team objects to the ZSR Library.