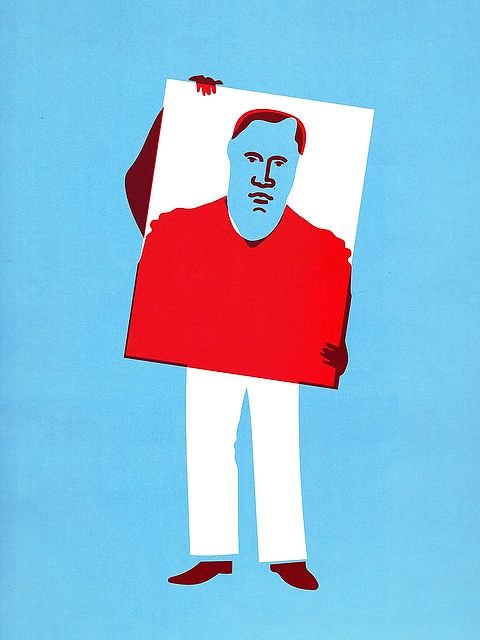

Eric G. Wilson, the

Thomas H. Pritchard

Professor of English,

is not himself

these days.

Or any days. Ever.

In fact, he claims to have no “himself” to be. Neither do you, nor do any of us.

Isn’t college — especially a “life of the mind” liberal arts college like Wake Forest — supposed to be where we go to find that essential self we have been all along?

Does the English department know, then, that its Thomas H. Pritchard professor instead professes, in his classroom and in his latest acclaimed book, that we all are self-created (or, worse, self-accepted) characters, playacting our way through life, faking it?

Does the University know? Does Thomas H. Pritchard!?

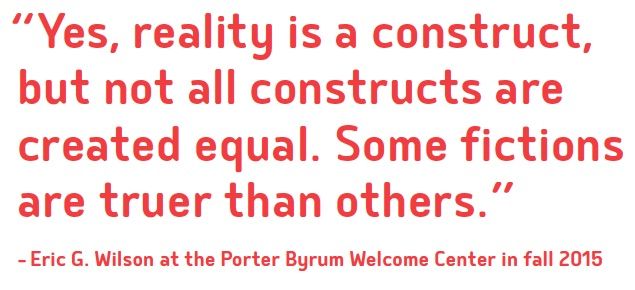

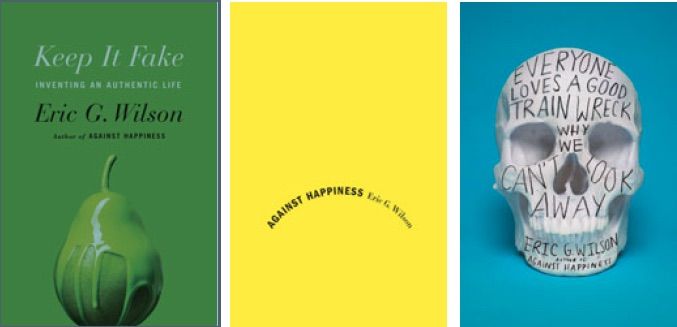

Wilson (MA ’90) argues for the reality of unreality in “Keep It Fake: Inventing an Authentic Life,” published in May 2015 by the Sarah Crichton Books imprint of the august publisher Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Like his three previous books of creative nonfiction, “Keep It Fake” has garnered national and international attention. The New York Times Book Review, Publishers Weekly and Kirkus Reviews are among those who have praised it on their pages. The Daily Beast, National Public Radio, even “The Art of Manliness” podcast all interviewed Wilson about the book and the claim he uses it to make: that we are better off when we quit trying to “be ourselves.”

To be clear: Wilson is, and is advocating for, faking it — not lying. Lies, he writes, are “deliberate put-ons that either harm others or help you or both together.” Even if Wilson admits “the possibility that both truth and lie are arbitrary antinomies — as are good and evil, rebellion and conformity, even, strange to say, life and death — in the collective narrative we have chosen to call reality,” he holds that lying is immoral because it is inauthentic — unlike playacting.

Playacting — choosing a role, an identity, from those available, and performing that role with grace and commitment and generosity — can be a profoundly moral act (pun intended), if we use our fakery to form as many genuine connections as possible.

We live in an age of reality TV, plastic surgery, performance-enhancing drugs, genetically engineered foods, a society in which we “trust Jon Stewart, the host of a mock news show, more than the serious anchors of the big four networks,” as Wilson writes in the book. “To be a fake in this dreamy universe is to believe in actual with the real is to know it’s all phony and create, with a generous heart, your own sweet ruse.”

“Keep It Fake,” Wilson said, was inspired by “my own struggle with questions about authenticity,” and the struggles with depression and bipolar disorder he wrote about in three of his previous books: “Against Happiness: In Praise of Melancholy,” “The Mercy of Eternity: A Memoir of Depression and Grace,” and “Everyone Loves a Good Train Wreck.”

Eric G. Wilson (MA '90)

“I’ve been in and out of a lot of psychotherapy over the years,” he said. “Early on, some psychotherapists I had were saying that, to be mentally healthy, you have to go through all the layers of fakery, all the different roles you play in life, and find this ‘real self,’ to get to this primal consciousness that is ‘you,’ and when you find that, well then, you’ll be happy and healthy.

“But I just found that so frustrating, and so limiting, over time. Finally I saw a psychotherapist who said, ‘There’s no such thing as a self. If you try for that, you’re going to be endlessly frustrated.’ It’s so liberating to think about constructing an identity and not being fake, if you inhabit that identity. That’s what authenticity is — constructing the role that you want, constructing the role that makes your life as vibrant as it can be, and inhabiting that role, and of course constantly revising that role as need be. Then life can become art.”

Long before he was Thomas H. Pritchard Professor of English, Wilson was “the boy whose first word was ‘ball,’ ” the coach’s son, the golden boy quarterback for his hometown team and — almost — for Army.

“But my mind,” he writes in his latest book, “from the first five minutes I was there, whispered over and over, like a prayer, ‘I’ve got to get the (ahem) out of here.’ ”

“Only when I … questioned quarterbacking and everything else did I doubt my parents’ honesty. There was no way I really blurted that word. Surely the coach wanted so much for my first word to be ‘ball’ that he translated my blubbery random b’s and l’s into his favorite sound. … (H)e thrust me into a narrative … by the time we become aware of ourselves we are already trapped in fictions not of our making, and our only hope of escaping the text is to write our way into stories of our own.”

Wilson began writing his own story by reading someone else’s.

Unable to leave West Point for 30 days, unable to sleep well at night, Wilson — no longer the quarterback, not yet a professor of English, still a teenager — tried to soothe his looming identity crisis by reading in his bunk after lightsout. By the combined glow of a sliver of moonlight and his Casio watch, he started “The Razor’s Edge” by W. Somerset Maugham — a book his mother had bought, and Wilson had brought, for no other reason than its cover photo of Bill Murray, his favorite actor (it was the tie-in edition to the 1984 movie, a flop).

Maugham’s novel tells the story of a traumatized World War I veteran who gives up the shining life waiting for him at home to go questing after Truth.

“I projected myself into his character: lived out my own struggles in his, explored a new identity as he fashioned one for himself,” Wilson writes. “(T)here in that West Point barracks bed, I concluded, for the first time, that I was interested in philosophy. … I said to myself, ‘I love poetry.’ ”

The story of his self that he began, there in his bunk by the light of the moon and his Casio, had the plot twists and digressions that any good story should. This new Eric Wilson he was creating (and daily creates) was neither stock nor static. He returned to his hometown of Taylorsville, North Carolina, to figure out his next steps, ending up at Appalachian State University in Boone, where he earned his bachelor’s degree. He followed that with a trip down the mountains for his first stint at Wake Forest, earning his master’s degree in English in 1990.

During these years, Wilson operated in the guise of the Serious Scholar. “I was quite staid,” he writes, “applying the inflexible discipline to my studies that I had once applied to football.

“It wasn’t until I reached graduate school that I mustered the guts to get weird.”

In the doctoral program at the City University of New York, he discovered a fascination for “the uncanny, the melancholy, the traumatic, the outlandish, the sublime,” which fueled his scholarly work on the Romantics.

He also came across the concepts and qualities that first he admired, then incorporated into his developing self, and now uses as the moral basis of “Keep It Fake” — “labyrinthine,” “capaciousness,” an openness to as many connections as the world will allow.

"Keep it Fake," "Against Happiness" and "Everyone Loves a Good Train Wreck" are among Wilson's books. He has said, 'The idea that there's no essential self is exhilarating.'

Referencing the work of the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur, Wilson writes that “some narratives are ethical, and some aren’t. Unethical stories are those unresponsive to the heterogeneity of the network, while ethical ones are sensitive to as many strands as possible. To create a narrative of such rich variety is not only good; it is beautiful, as the novels of Woolf, Faulkner, Proust and Joyce are: capacious, multiple, polyvocal, rhythmical, generous. The fading of fact into fiction generates an ethic that is aesthetic.”

Wilson returned to Wake as an assistant professor of English in 1998, becoming a full professor in 2006 and the Thomas H. Pritchard Professor of English the following year. He served as the chair of the English department from 2003 – 2007 and as director of the Master of Arts in Liberal Studies program from 2008 – 2010.

Nowadays the 48-year-old Wilson teaches mostly undergraduate courses on topics such as “The Gothic” and “American Romanticism,” filled with digital natives who, on social media, have been choosing and curating their own personae for most of their lives.

“The notion that there’s no ‘true self ’ is not such a shocking idea now,” Wilson said. “They’ve experienced, and have accepted, that there’s a fluidity to identity, that identity is a process. You’re not meant to conform to who you were at 16.”

The danger in accepting the fluidity of identity is when the identity you create is “not one that will enrich your life.”

“There are realities; things happen. There are givens,” Wilson said. “If you create an identity that is at odds with the givens, that’s an unsatisfying life.

“The best identities are those that are able to accommodate those givens, and make them meaningful. Some identities are more meaningful than others.”

In class Wilson often illustrates this idea with what he calls “the metaphor of the cliff ”:

“Just as gravity will throw us into the sea if we leap from a coastline cliff, our genes and a multitude of other factors will force us into actions over which we have no control,” he put it in a blog post for Psychology Today. “But we can decide how to fall — flail wildly and smack the water in a bellyflop, or arc into a swan before entering the blue with nary a splash.”

He may not be able to create himself out of whole cloth — he can never not be “the boy whose first word was ‘ball’ ” — but he can stitch together his “givens” into new, more vibrant patterns.

“The past is a constant, as much as the present and future. If you fall into a depression or a crisis, though, you can focus on other parts of your past,” Wilson said. “There’s always a space for creativity. We have the ability to swerve from our past. We can interpret those past acts in different ways.”

“Keep It Fake” is Wilson’s fourth book of creative nonfiction (he also has published nine scholarly books), and in many ways this one intersects the most with his work in the classroom.

“The ideas that show up in the book are ideas I constantly talk about in my classroom. If I can make my ideas clear to 19-year-olds, if I can turn them on to those ideas, then I’ve got something.

“I’m still profoundly formed by the major ideas of Romanticism. If I can sum them up, it’s ‘the redemptive power of the imagination,’ the idea that we can shape our lives by how we imagine our lives, that we can turn life into art.

“The voice that I tried to capture in ‘Keep It Fake’, the voice that excites me the most, is precisely my teaching voice. I think I’m livelier during those moments when I’m teaching. The voice that I have when I’m teaching is very sensitive to others.

“I really like myself when I teach.”

Ed Southern (’94) is the executive director of the North Carolina Writers’ Network and the author of “Parlous Angels” and “Voices of the American Revolution in the Carolinas.” He lives in Winston-Salem.