Flannery O’Connor had Andalusia outside Milledgeville, Georgia. Eudora Welty had Jackson, Mississippi. Betsy Wakefield Teter (’80) has the place where she was born: Hub City, an old moniker for Spartanburg, South Carolina, which she helped revive, both the nickname and the city.

Betsy Wakefield Teter ('80)

Not that Betsy is a Southern novelist. She did win two fiction prizes as an undergraduate history major at Wake Forest with a plan to become a fiction writer, “until I went into journalism, which will beat that out of you.” She spent 16 years working at newspapers in South Carolina, in the end serving as a columnist and business editor of the Spartanburg Herald-Journal, where she occasionally — and naturally — thumped heads with the city’s business leaders. She left the newspaper job in 1993. Two years later, she would co-create a venture whose success was unimaginable 21 years ago but now has authors of place-based literature highlighting the Southern experience beating a path to Betsy’s door.

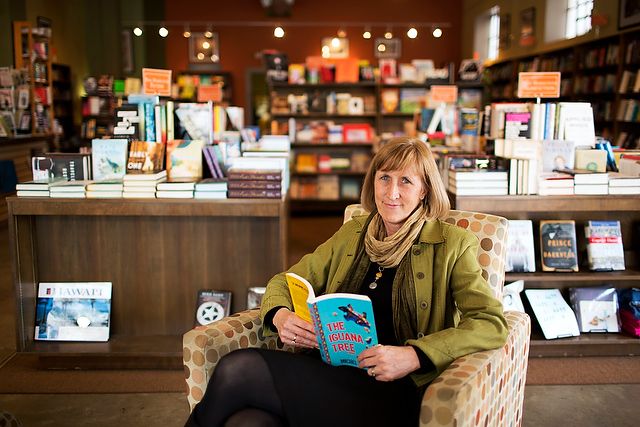

On a January afternoon I find her across the street from her old newspaper office, presiding over a literary epicenter that sits in the renovated Masonic Temple on the western stretch of Main Street, bordered by Daniel Morgan Avenue and Honorary Teter Lane, named by the city council in praise of Betsy and her husband, John Lane, it must be noted, years after Betsy left the notoriously non-boosterish newspaper business.

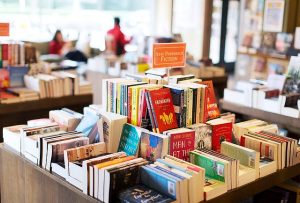

She settles herself onto a couch beside the sunny front window of the rarest of treasures these days — an independent bookstore and, in this case — even rarer — a nonprofit independent bookstore called Hub City Bookshop that she founded in 2010. A plaque on a wall beside her lists the many donors who rallied to the cause. This is where Betsy oversees Hub City Press, which has offices in the back of the bookshop and 74 titles in print, and where she and her team of three full-time and three part-time employees sells books, hosts authors’ Q&As, sponsors writing workshops, examines manuscripts from aspiring authors and, with an advisory committee, typically selects five to six manuscripts a year to publish. Revenues from the little bookshop on the corner help pay for a summer writers conference, a writers-in-residency program, college scholarships, writing prizes and donations of books to local schoolchildren for summer reading. Wiley Cash, a New York Times best-selling author based in Wilmington, North Carolina, told Publisher’s Weekly last year the bookshop has been “a huge support to writers like me” and is “single-handedly holding down the arts” in what is now a flourishing arts scene in Spartanburg.

In size and décor with its huge windows, industrial-style ceiling and artwork, the store reminds me of Book Passages in San Francisco’s Ferry Building without the view of the Bay. The smell of fresh-brewed coffee wafts in from The Coffee Bar, and so do the customers, steaming cups in hand. The bookshop rents the adjacent space to the owners of the coffee house and Cakehead Bakery. In and out of the first-floor shops wander city visitors, families, business people and artsy teens. The vocals of Norah Jones and the Dixie Chicks play in the background. Customers are eyeing New York Times best-sellers and books published by Hub City Press, which have won 13 Independent Publisher Book Awards. I find it comforting if bittersweet in this digital age to meander among shelves of books I never knew I needed, whose heft I’ve missed and whose pages feel as sacred as conservators’ parchment. The word “Temple” minus “Masonic” on the outside of the building seems apt for the book reverence inside. So many of us miss the independent bookstores that signal a thriving downtown. This is Spartanburg’s literary green light.

Betsy calls her own books “trophies,” and I can relate. She treasures and admires them for the beauty of their covers and the possibility each new volume will rank as “that one perfect book” she is always seeking. In them is the invitation for transformation through poetry and prose. At home she and her husband have collected 5,000. By her count, she reads a novel a week. What better person to run a nonprofit bookstore, a publishing house and a literary movement?

“Our mission statement says that we nurture writers and cultivate readers,” Betsy says. “We’re a nonprofit organization, and if we are helping convince people to read a book we’ve done our job.” To understand the model, think of museum stores. “This is what in the nonprofit field is called ‘earned income,’ ” she says, which is plowed back into supporting the mission. She figures there are fewer than five bookstores like this “literary center” in the country, and this one, she says, is growing.

“If you can describe the ambition, it would be Algonquin crossed with Square Books in Oxford,” she says, referring to the renowned literary publishing house founded in 1983 in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and the Mississippi bookstore of national acclaim. “They are so good for their community. They’ve changed their community, and I know we’ve changed our community. We’ve sort of married those two ideas.”

“If you can describe the ambition, it would be Algonquin crossed with Square Books in Oxford,” she says, referring to the renowned literary publishing house founded in 1983 in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and the Mississippi bookstore of national acclaim. “They are so good for their community. They’ve changed their community, and I know we’ve changed our community. We’ve sort of married those two ideas.”

The bookstore is in the renovated Masonic Temple on Main Street.

THE GENESIS OF all things Hub City modern began downtown at a now-defunct coffee shop in 1995. Three writers bent over a napkin and devised a plan to publish one book, emphasis on one. Besides Betsy, who by this time was raising two boys and working as a freelancer, at the table were her newspaper colleague Gary Henderson and John Lane, a poet and Wofford College professor. (Years later, John and Betsy would marry.) Spartanburg had a proud history but was down and out after the textile industry collapsed, its downtown dried up. “We were still here because we liked living here. Maybe there was not a lot going on, but we all had this deep tie, maybe because of the way we had been raised, … to care deeply about our community,” Betsy says. She was a third-generation Spartanburgian. Her parents were civic-minded; her dad owned the Buick dealership, just as his father before him, and he always rooted for downtown progress. Betsy inherited his business acumen and practical ability to take a creative idea and run with it. But the three writers believed economic development and a tax base didn’t define a community fully. “The soul is in its stories,” John says. “We wanted to show this community that we had a soul.”

Flannery O’Connor

John dug into Spartanburg’s history, discovering it had been widely known in the early 1900s as Hub City thanks to its many railroad tracks. “(C)onfident of whatever else happened to me,” the essayist E.B. White once wrote, “the railroad would always pick me up and carry me here and there, to and fro.” Long ago, his sentiments might have been shared by residents of Spartanburg with her passenger lines radiating outward and her grand pronouncement: “A glimpse at the map will show the city of Spartanburg to resemble the hub of a great wheel with spokes running in five directions. … Spartanburg is emphatically the gateway to the Western World.” The coffee klatch writers named their fledgling organization the Hub City Writers Project and decided to produce the book, complete with the “hub” quote and a title: “Hub City Anthology.” They modeled themselves after the Federal Writers’ Project in which the federal government employed writers, historians, librarians and teachers to document the nation’s culture during the Great Depression.

John says the echo was intentional: “A community can be in a great depression and not even know it. To say it is to admit you’re defeated.” They envisioned a book that would give Spartanburg a literary identity. They planned to feature essays by 12 writers and works by local artists. “Black writers, white writers, older, younger, natives, newcomers — everybody wrote a little piece about Spartanburg,” Betsy says. With no money or experience, Hub City Writers Project designed a brochure Betsy laments “looked like something you’d make in the fourth grade.” They mailed the brochures to wealthy donors, who were promised a collectors’ hardback edition of the anthology with their names in the front and a tax deduction if they contributed $100. The group hoped for 100 checks and received 120. “We were early crowdsourcers, absolutely,” says Betsy.

John says the echo was intentional: “A community can be in a great depression and not even know it. To say it is to admit you’re defeated.” They envisioned a book that would give Spartanburg a literary identity. They planned to feature essays by 12 writers and works by local artists. “Black writers, white writers, older, younger, natives, newcomers — everybody wrote a little piece about Spartanburg,” Betsy says. With no money or experience, Hub City Writers Project designed a brochure Betsy laments “looked like something you’d make in the fourth grade.” They mailed the brochures to wealthy donors, who were promised a collectors’ hardback edition of the anthology with their names in the front and a tax deduction if they contributed $100. The group hoped for 100 checks and received 120. “We were early crowdsourcers, absolutely,” says Betsy.

They held the book launch in the old train depot in April 1996. There was a traffic jam. So many people showed up and spread along the train tracks, the writers couldn’t conduct the reading. “I think we sold 700 books that first day. It was incredible,” Betsy says. “I think people had a deep longing for some way to celebrate their community and understand it and bring people together around the idea of Spartanburg. You know, it’s a town in the shadow of Greenville. We’ve made mistake after mistake here. So we struggle, and we want to feel great about ourselves. We are good people in our town.”

They held the book launch in the old train depot in April 1996. There was a traffic jam. So many people showed up and spread along the train tracks, the writers couldn’t conduct the reading. “I think we sold 700 books that first day. It was incredible,” Betsy says. “I think people had a deep longing for some way to celebrate their community and understand it and bring people together around the idea of Spartanburg. You know, it’s a town in the shadow of Greenville. We’ve made mistake after mistake here. So we struggle, and we want to feel great about ourselves. We are good people in our town.”

Betsy’s essay, “Magnolia,” was featured in the book. Of Spartanburg, she wrote, “I believe it is a place of consequence.” Of herself, she wrote, “I am no pioneer. I am a root seeker, a nest clinger.”

Fellow citizens in this city of 37,647 would disagree. They see Betsy as a pioneer, a woman of consequence. “It’s fun to watch her,” former Spartanburg Mayor Bill Barnet tells me. “It’s fun to watch someone be successful.” When he prepared to retire in 2010, he urged people to support the vision for establishing the bookstore, not a retirement party. “She’s really attracting attention and deservedly so. … She’s the Energizer Bunny, always plugging along doing good things,” he says.

Todd Stephens, director of the Spartanburg County Public Libraries, says, “Clearly, she’s had an impact on downtown Spartanburg and its development without a doubt.” In what was a part of downtown lagging in revitalization, the bookshop opened and has welcomed new neighbors: a restaurant, a fancy wine shop, a brewery and a 10-story boutique hotel under construction. Betsy has made it “her life’s work” to improve the city, he says, and she has done that by “connecting people to the written word.” Chris Jennings, executive director of the Spartanburg Convention & Visitors Bureau, calls her “our hometown hero.” She is the recipient of the bureau’s 2016 tourism award. “Betsy has the big picture,” he says.

Todd Stephens, director of the Spartanburg County Public Libraries, says, “Clearly, she’s had an impact on downtown Spartanburg and its development without a doubt.” In what was a part of downtown lagging in revitalization, the bookshop opened and has welcomed new neighbors: a restaurant, a fancy wine shop, a brewery and a 10-story boutique hotel under construction. Betsy has made it “her life’s work” to improve the city, he says, and she has done that by “connecting people to the written word.” Chris Jennings, executive director of the Spartanburg Convention & Visitors Bureau, calls her “our hometown hero.” She is the recipient of the bureau’s 2016 tourism award. “Betsy has the big picture,” he says.

When it came to selecting her college, she had only one picture in mind: Wake Forest. She applied early decision, intent on writing and pursuing her love of ACC basketball. Tall and lean to this day, she’s built like an athlete, but she wasn’t good enough at hoops to play in college. She moved into Bostwick 2-B and formed close ties with her hall mates. “Thirty-five years later most of us are still seeing each other.” As first-year students, she and her friend Catherine Woodard (’80, P ’13) plopped down on the floor in Reynolds Gym so they could claim the first student tickets for the ACC basketball tournament. Their friends stood in for them while the two superfans went to class. “We took our sleeping bags, and the line formed behind us all four years,” she says proudly. She remembers her favorite history professors, David Smiley (P ’74) and Howell Smith (P ’84, ’91), and her fascination with people “coming and going” in historic movements, from the South to the North with the rise of the automobile industry, from Appalachia to the mill villages in textile towns like hers.

There is some irony that she says, “I’m a Southern girl and don’t think I’ve ever imagined a moment in my life leaving the South.” No out-migration for her. Instead, she is content to stay and shepherd Hub City Writers Project, the big tent for Hub City Press, the Hub City Bookshop and, for a while, HUB-BUB, a cultural organization backed by the city and devoted to promoting art, music and film. “It was a real renaissance in this town, but it just about killed me,” Betsy says of her time overseeing Hub City Writers Project’s work and HUB-BUB. With HUB-BUB alone, “we were doing 100 to 150 events a year.” Eventually, Betsy decided to run only one organization: Hub City, and HUB-BUB went out on its own.

Through these 21 years, her enthusiasm for literature and community hasn’t waned nor has her devotion to helping writers at any stage of development. Michel Stone of Spartanburg is one of them. “I was a mom who had never published anything,” she says. For years she attended the annual writing conference at Wofford College sponsored by Hub City Writers Project. Then she won a Hub City writing fellowship to attend a summer program at Wildacres Retreat in North Carolina. A short story she was crafting became a novel, and the publisher was Hub City Press. With Betsy as a publicist displaying the deal-making skills befitting a car dealer’s daughter, “The Iguana Tree” sold 15,000 copies, won a 2012 Independent Publisher Book Award and launched Stone on a book tour around the country.

Through these 21 years, her enthusiasm for literature and community hasn’t waned nor has her devotion to helping writers at any stage of development. Michel Stone of Spartanburg is one of them. “I was a mom who had never published anything,” she says. For years she attended the annual writing conference at Wofford College sponsored by Hub City Writers Project. Then she won a Hub City writing fellowship to attend a summer program at Wildacres Retreat in North Carolina. A short story she was crafting became a novel, and the publisher was Hub City Press. With Betsy as a publicist displaying the deal-making skills befitting a car dealer’s daughter, “The Iguana Tree” sold 15,000 copies, won a 2012 Independent Publisher Book Award and launched Stone on a book tour around the country.

“It has opened up the world for me, and now I’m sitting at my kitchen table emailing Nan Talese,” Stone says. Her second novel, “Border Child,” will be published by Nan A. Talese/Doubleday in 2017. “Betsy was as excited as I was,” Stone says of her contract with Talese, a revered editor and publisher in New York. Stone says Betsy “has never lost sight of how she wanted to nurture emerging writers and establish writers who have a sense of place.” Stone has nominated Betsy for South Carolina’s highest arts honor, the Elizabeth O’Neill Verner Award. (Hub City Writers Project won in 2002, but it was time for Betsy as an individual to be honored, Stone and other recommenders told me.)

Betsy once said of Hub City Writers Project: “We reflect our community, and that’s what makes us successful.” In Spartanburg, Betsy is all about community, calling her team her biggest asset and making sure to bestow credit on a long roster of citizens promoting writing and reading. Still, it’s not too much of a stretch to call Betsy Wakefield Teter the hub of Hub City — the visionary who never loses sight of her city’s soul, its storytellers or her personal goal to be the best publisher in the South.

Betsy once said of Hub City Writers Project: “We reflect our community, and that’s what makes us successful.” In Spartanburg, Betsy is all about community, calling her team her biggest asset and making sure to bestow credit on a long roster of citizens promoting writing and reading. Still, it’s not too much of a stretch to call Betsy Wakefield Teter the hub of Hub City — the visionary who never loses sight of her city’s soul, its storytellers or her personal goal to be the best publisher in the South.

Betsy Wakefield Teter's Picks

SOUTHERN NOVELS EVERYONE SHOULD READ:

“Wise Blood” by Flannery O’Connor

“Lie Down In Darkness” by William Styron

“The Color Purple” by Alice Walker

“Edisto” by Padgett Powell

RECENT SOUTHERN FICTION:

“Something Rich and Strange: Selected Stories” by Ron Rash

“All I Have In This World” by Michael Parker

“The Tilted World” by Beth Ann Fennelly and Tom Franklin

“Fallen Land” by Taylor Brown

“Byrd” by Kim Church

HUB CITY BEST-SELLERS:

“The Iguana Tree” by Michel Stone

“Minnow” by James McTeer

“Carolina Writers at Home” edited by Meg Reid

“The Whiskey Baron” by Jon Sealy

TRIBUTES

On Mother’s Day in 2015, former writers in residence returned to Spartanburg to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Hub City Writers Project, which sponsored their residencies. They honored the project but also toasted their patron saint, Betsy Wakefield Teter (’80). Following are excerpts:

“I came to Spartanburg because of Betsy and I stayed here because no one person, save for my family, has ever invested so much in me and asked for so little in return. She’s taught me a kind of generosity that I will aspire to always, to give so brilliantly and passionately that you inspire the rest of the world to give along with you.”

— poet Eric Kocher, formerly of Baldwin, New York

“IF HUB CITY BOOKSHOP ISN’T THE PLACE WHERE EVERYBODY KNOWS YOUR NAME, IT’S AT LEAST THE PLACE WHERE EVERYBODY KNOWS BETSY TETER. … I’VE GOTTEN TO KNOW THIS COMMUNITY, AND ONE FACT HAS BECOME VERY OBVIOUS: IT’S NOT JUST THAT THE LITERARY SCENE IN SPARTANBURG WOULD BE LESSER WITHOUT BETSY; IT WOULDN’T EXIST.”

— poet and teacher Casey Patrick of Minneapolis

“I want to say that if I could be a superhero my answer would be Betsy Teter — but I think what makes her even more heroic is that she didn’t come from space or wasn’t bestowed powers but has an innate understanding of her personal power: what it means, and how to use it. We can see how clearly she has used it for Spartanburg, out of joy and love, and how that spread to writers and artists not just throughout the South but nationally.”

— Corinne Manning, writer, editor and teacher in Seattle

“BETSY GAVE ME THE BEST YEAR OF MY LIFE, AND SHE TAUGHT ME WHAT IT MEANS TO TRULY FIND HOME.”

— Jameelah Lang, whose Ph.D. is in creative nonfiction from the University of Houston