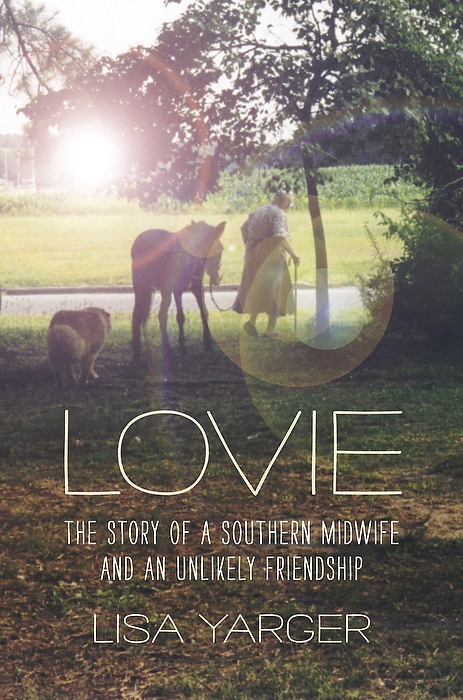

Lisa Yarger (’89) is the author of a new book, Lovie: The Story of a Southern Midwife and an Unlikely Friendship, (UNC Press in association with the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University) that was nearly 20 years in the research and writing. She responded to several questions from Wake Forest Magazine.

How did the idea for the book come about, and what was it like for the story to unfold over so many years?

In 1996 I was working as a folklorist for the North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh. We had a big exhibit on health in the works, and I was looking for an African-American lay midwife from eastern North Carolina to help us tell the important story of midwife-attended home births from that part of the state. Unfortunately I couldn’t find a black midwife who was still alive. Then I heard about this white, professionally trained nurse-midwife in Beaufort County named Lovie Beard Shelton, who had been delivering babies in eastern North Carolina homes for nearly 50 years. This wasn’t exactly what I was looking for, but Lovie sounded interesting, so I arranged to visit her.

Author Lisa Yarger (left) and North Carolina nurse-midwife Lovie Beard Shelton.<br /> Photo by Shanna Marie Shaffer.

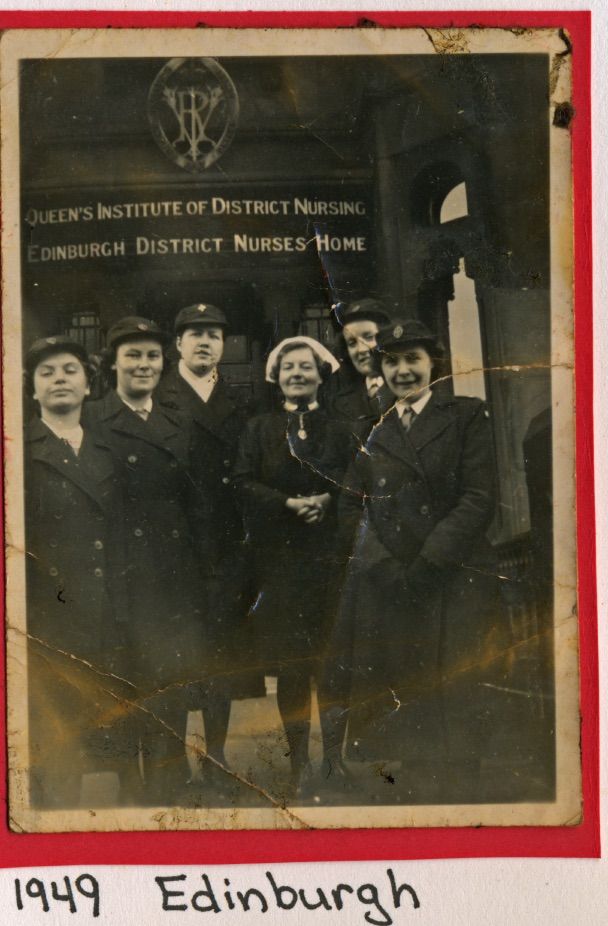

When I met Lovie, I knew I was in the presence of someone special. Her credentials themselves were impressive: she had traveled from rural North Carolina to Scotland in 1949 to study under a world-famous midwifery teacher (Margaret Myles) because nurse-midwifery was almost unheard of in the United States and there were few training spots; she had returned to North Carolina to become the first public health nurse in Pamlico County as well as the first nurse-midwife in the state; she had delivered some 4000 babies, mostly African-American; and along the way she had also raised four children.

But it was the more literary aspects of Lovie’s life that gave me the idea for the book. Here was a midwife so taken by the story of Jesus’ birth that she kept a mule in her back yard to remind her of pregnant Mary riding a donkey into Bethlehem; Lovie also liked to think that there had been a midwife assisting at Jesus’ birth, even though “the Bible forgot to mention it.” Additionally, this was a woman who had devoted her life to bringing new life into the world yet had endured devastating losses, including the sudden death of her husband, the murder of her oldest son, and the accident that left her younger son partially paralyzed. She grieved for these losses as long as I knew her, but she was also an extremely funny person who seemed keenly aware of herself as a character; she delivered lines as though she knew they’d go right into my book.

As for the story unfolding over so many years, well, that wasn’t planned! I had been wanting to take on a book-length creative writing project, and I somehow had the idea that writing a narrative nonfiction account of a real person would be easier than writing a novel. This turned out to be very naive. For one thing, the ethical and moral implications of writing about an actual person are enormous, and I had a hard time getting clear on where my obligations to Lovie ended and where my obligations to myself began.

Then, too, the longer the research process went on, the more it became clear that I needed to write myself into the book, otherwise the reader would start to wonder where all this material was coming from and just whose perspective was shaping the story. Turning myself into a character was more challenging than writing about Lovie. Obviously this isn’t my memoir, but there are memoirist parts to the book; as the reader’s guide to Lovie, I needed to show enough of myself to get the reader to trust me, to take my hand as we together got to know this remarkable person and the world she occupied.

Why was this an important story for you to share?

I wanted to give Lovie what she seemed to crave: recognition and a place in history. Equally important, I saw for myself an amazing subject and rich material and the opportunity to bring this singular woman to life on the page for others.

Lovie at about age 12 with one of her father's mules.<br /> Photo courtesy of Lovie's sister, Octavia Bowman.

Could you describe your evolving friendship with Lovie?

At first we were rather formal with each other: two professional women collaborating on a professional project. And of course we mostly were talking about her work. After the exhibit opened and I asked if I could write about her, things relaxed somewhat. (She invited me to stay in her home for several days, for example.) Lovie’s yard was extremely important to her, and once I started helping her with various yard projects, things loosened up even more, and our relationship grew to include aspects of her life that had nothing to do with her career. We could have fun together, we could laugh and joke together; I would say that we became friends. But it was a peculiar, lopsided kind of friendship, in that Lovie never really knew that much about me. If you’d asked her, she couldn’t have told you anything about my family or my childhood, for example.

Two things interested her: my love life (I was 29 and single when we met) and whether or not I was going to church. I ended up weaving those threads into the book, because I did meet and marry my husband in those years that I was spending time with Lovie, and the church theme kept popping up because Lovie kept asking about it and because I found myself having strong reactions to her attempts to pin me down. That’s another aspect of our relationship that I explore in the book: Lovie’s and my attempts to pin each other down and how successful those efforts ultimately were. To sum up: Lovie and I were very fond of each other, and our relationship was often fraught.

What sparked your interest in writing and storytelling?

My maternal grandfather, who grew up in a German-American community outside of St. Louis, was an expert storyteller; it was from him that I first had an appreciation of a good story well told. His stories all came from real life experiences – mostly his own, but also from people he knew – and gave me a sense of how one could artfully transform little nuggets of daily life into compelling stories.

Lisa Yarger on her youth: 'I see now how hungry I was then for stories about women.'<br /> Photo by Sabine Kueckelmann.

As a girl I read primarily fiction, but I also read (many times over) all of the biographies of women in a particular series in my elementary school library. This was in the 1970s, and the series was quite dated, but there were nonetheless amazing women to be found in it: Harriet Tubman, Marie Curie, Juliet Ward Howe, Eleanor Roosevelt. I see now how hungry I was then for stories about women. How did they make their way through the world, what choices did they make, how did they fare given the sexism, racism and other oppressions confronting them?

In high school I had one amazing English teacher after the other, each of whom shared her infectious love of literature. Before my senior year I attended Governor’s School West in English and had classes with Lucy Milner (who went on to direct GSW and is very much a part of the Wake Forest community); that was the summer I fell in love with Winston-Salem and (thanks to Milner) the short stories of Flannery O’Connor. At Wake Forest I declared myself an English major, and while pounding out decent articles for the Old Gold and Black as well as solid academic papers, I started to think I might like to write creatively someday, though I had no idea how to get started. I regret that I never took a creative writing class at WFU; I could have taken one with Maya Angelou, then the Reynolds Professor of American Studies, but I was terrified that I might find out that creative writing wasn’t my thing. So while a number of my friends took and enjoyed her class, I acted as though I already knew what I needed to know and didn’t need creative writing instruction. Sigh …

I started moving in a creative writing direction during two brief stints at the Winston-Salem Journal. I always preferred writing personal profiles, what newspapers call “human interest” stories, as opposed to hard news. I wrote as many human interest stories as I could get away with and avoided the hard news where possible, in part because hard news often involved conflict, and conflict scared me back then, but also because I invariably forgot some critical detail in the news stories. Once I submitted a story about a fire without bothering to find out how the fire had started. (No one had been injured, and I suppose I wasn’t all that curious about it.)

Lovie in her yard in Washington, North Carolina, circa 2000.<br /> Photo by Lisa Yarger.

A few years after graduation I was working for a non-profit in Washington, D.C., trying to decide my next move, when my anthropologist boyfriend pointed me toward folklore studies. I had little sense of what a folklorist did beyond interviewing people and writing about them, but that was enough for me. I got a master’s in folklore from UNC-Chapel Hill, which led to the museum job, which led me to Lovie.

When did you move to Munich, and what is it like to live abroad and manage a bookshop? Do you miss the USA?

In 2005 I gave birth to a daughter; four months later we packed up our lives and moved to Munich to open a bookshop. (I do not recommend this approach to major life changes.) Things were tough at the beginning, but after 11 years I feel planted here.

Our bookstore attracts people from around the world who are visiting or who make their home in Munich, and it’s a treat to welcome them to our shop. John Browner, my husband, is the book seller and businessman; I handle our events. When our daughter was small I started doing Saturday morning readings for children: my goal with these has always been to get kids laughing. Eventually I figured out that I could use the bookshop as a platform to do whatever I wanted. With children, for example, I like to share books that are somewhat irreverent, as well as stories that show how young people are inherently powerful and intelligent. I’ve gone on to create and host anti-racism events, writing workshops and a monthly open reading. Through these I’ve met people from around the world who have become friends.

There’s a lot I miss about the United States. Above all I miss my family and friends. I miss North Carolina and I miss Durham, where we lived before our move. I miss the ease with which one can fall into conversation with a stranger while waiting in line at the grocery store or walking the dog. And there’s a certain flexibility and spontaneity to US culture that I miss, especially as it’s connected to creativity. This might be a strange example, but what comes to mind is a former neighbor in Durham who set up a little memorial to her dead cat in her front yard, complete with a laminated photo of the cat, a one-page typed tribute to the 18 years she’d shared with the cat, and flowers in a vase. All the neighbors knew the cat and everybody noticed its absence, and this was the woman’s way of letting us know the cat was gone and why the cat had been special to her. When I visit the U.S. I always notice unexpected bursts of creativity like that.

So all of that I miss. On the other hand, it’s been incredibly valuable to have a perspective on my country from the other side of the Atlantic.

Lovie, third from left, with sister midwifery pupils in Edinburgh, 1949.<br /> The woman in the white cap is likely a tutor.<br /> Photo courtesy Carolyn Ellison.

Looking back on your time at WFU, were there experiences and/or mentors who shaped you as a person, as well as the path you have followed?

I ended up at Wake Forest because of David Smiley. The summer before my senior year of high school I stopped by campus with my parents just to look around, and we happened to run into Dr. Smiley, who immediately took us under his wing and gave us a tour. I was already interested in WFU but his warmth and welcome sealed the deal. I never had a class with him but remember how, after a rainfall, he used to pick worms up off the sidewalks on the Quad and gently place them onto the grass; in my middle age I have also become a rescuer of stranded worms and think of Dr. Smiley whenever I move one to safety.

While I no longer remember which classes I took during the first semester of my freshman year, I’ll never forget the excitement I felt when it suddenly dawned on me that all my seemingly disparate courses were actually connected. (The beauty of a liberal arts education!) I had been a good student in high school but always had an eye on pleasing the adults around me; at WFU I discovered the joy of learning for myself, because things interested me. The classes that had the biggest impact on me were Charles Lewis’ introduction to philosophy (he famously awarded only one A per class; the A went to someone else but I ended up with a B+++++ and an encouragement to take more philosophy, which I did); modern drama with Nancy Cotton (eye-opening readings that shaped my love of dialogue), and Blake, Yeats and Thomas with Edwin Wilson (surely I took notes in that class but I mostly remember just being enchanted.)

Beyond academics: in the Outing Club I discovered a love of hiking, swimming in rivers and sleeping under the stars; on the Old Gold and Black staff I learned the pleasure working as a team to create something more than one could on one’s own; and in the Catholic Student Association, I developed deep personal connections and a bigger picture of the poverty and oppression faced by individuals and communities outside of my protected bubble. I still have close connections with many of the women and men I met in those organizations and still marvel at my luck in having shared my time at WFU with them.

Lisa Yarger (’89), a Carswell Scholar, graduated magna cum laude with a degree in English. She and her husband and daughter live in Munich, Germany, where they own and operate an English secondhand book shop, The Munich Readery.