Editor’s note: this article was originally published in the Raleigh News and Observer on Dec. 31, 2016. It is reprinted with permission.

RALEIGH — About 17 years ago, John Kane looked at a failing mall on polluted soil and saw the future of Raleigh.

He would clean the dirt contaminated by a gasoline station on Six Forks Road. He would end North Hills’ life as an indoor mall.

And even with one of the region’s most popular retail centers, Crabtree Valley Mall, three miles down the road, Kane would erect one of the city’s premier destinations not only for shopping but also for working and living all in one place.

Kane, by paying meticulous attention to detail and collaborating with residents, “took the fear out of density,” says former Raleigh planning director Mitch Silver, and turned Raleigh into a 21st-century city.

“It wasn’t just about the buildings. It was about the space in between the buildings,” says Silver, who now works as New York City’s parks commissioner.

Kane emerges as one of the Triangle's most successful deal makers, a catalyst for growth and mass transit. (Photo by Travis Long/Raleigh News and Observer)

“Most cities rely on a hub and a spoke, but it’s better to be a poly-centric city,” Silver says. “People want to have choices and places they can go. It’s unique Raleigh can pull that off.”

Now, the man who helped whet Raleigh’s appetite for urban living is helping transform the city again.

His latest infill projects aim to change downtown Raleigh’s landscape while maintaining its character. And his influence in the political arena will help change the way Wake County residents commute and enjoy life outdoors for decades to come.

Kane Realty last year finished Stanhope, an apartment complex that caters to students with street-level retail on Hillsborough Street, setting the tone for other developers near N.C. State University. Meanwhile, The Dillon, a 17-story mixed-use tower on West Street downtown, is rising from the bones of an old warehouse to feed off Union Station, the city’s future transit hub.

Raleigh's skyline (Photo/Google Maps)

Kane believes mass transit is important for a growing city. He helped craft the Wake Transit Plan, a vision to bring commuter rail and enhanced bus service to Wake over the next decade, and promoted the recent half-cent sales tax referendum that will help fund it. His political connections also helped bring about the 2015 sale of the former Dorothea Dix psychiatric hospital campus to the city of Raleigh for a park.

In an increasingly liberal city that’s sometimes uneasy with the changes brought on by growth, Kane remains a respected Republican developer and deal-maker. The key to success, Kane says, comes from a simple philosophy: “It doesn’t have to be my idea; it just has to be the best idea.”

Impulsive once

John Merritt Kane grew up in Henderson, an hour north of Raleigh, and graduated from Wake Forest University in 1974 with a business degree.

Kane says he was never the smartest kid in class, but that he always worked hard and knew at an early age that he wanted to build things.

After working for his dad’s construction firm for four years, Kane assembled enough investors to help him buy a 220,000-square-foot shopping center in Greenville in Eastern North Carolina. So in 1978, Kane rented a two-bedroom apartment nearby and moved there to start his own business.

The man who helped whet Raleigh’s appetite for urban living is helping transform the city again. (Photo by Travis Long/Raleigh News and Observer)

With the weight of a business on his shoulders, Kane adopted a new-found sense of discipline that he applied to every aspect of his life. “He would get up, put on a suit, go into the other room and go to work,” his wife, Willa, recalls.

Willa witnessed what was likely Kane’s last big, impulsive decision because she was also the cause of it. It came after their first date.

“I asked to marry her about three weeks later,” Kane says. “It was kind of like love at first sight.”

The couple’s decision to marry still stands as the most spontaneous thing they’ve ever done. They married about a year later.

They laugh about it now, though they kept their engagement story a secret for years from their four children.

“We weren’t trying to lie to them, but it was prudent to not tell them what a whirlwind romance we had,” Willa says. “The more marriages we’ve watched, the more we’ve realized that marriage is work. Given how quickly we fell in love, we’re extremely fortunate that it’s turned into a long, healthy marriage.”

Stanhope student apartment complex (Photo/Google Maps)

Turning point

Kane, 64, now looks out his second-floor office window above a North Hills jeweler onto the 18-story Bank of America tower he built on the other side of Six Forks Road.

His wooden desk is nearly as long and wide as the Maserati he leases. The furniture matches the tobacco-colored walls, and his coffee-table books feature photos of famous skyscrapers from around the world – many of which Kane has visited.

Kane’s career isn’t defined by North Hills so much as measured by it.

There’s pre-North Hills John Kane, who mostly focused on suburban retail centers and owned a slew of exercise gyms. Then there’s post-North Hills John Kane, Raleigh tower-builder and advocate for urban lifestyles.

“Once you work in an environment like this or live in an environment like this, you think to yourself, ‘Why would I want to be in the suburbs?’ ” says Kane, who lives in a 9,700-square-foot, $2.2 million house on Drummond Drive just a mile away from his office.

“You can walk to the Starbucks and hang out, go to the movies, go to the gym or go to the store and get Christmas presents,” he says. “I can do anything I want right here, and that’s pretty sweet.”

Downtown Raleigh, North Carolina (Photo/Google Maps)

Kane’s blond hair is turning gray. He now absorbs his environment through thick tortoise-shell glasses, and he’s not as athletic as he was when he played for the golf team at Wake Forest.

But some things haven’t changed. Kane, whose family has a history of heart disease, still works out every day. And his modest, trim frame still fits well into pressed slacks and tailored jackets.

He’s also as organized as ever, because he needs to be. Not only is he chairman and CEO of Kane Realty, which employs 153 people, he holds leadership positions for organizations throughout the community, including governing boards for RDU International Airport, the N.C. Chamber of Commerce, the Duke University Health system and the Research Triangle Regional Partnership.

His days are cluttered with conference calls, staff meetings and networking events. He’s often the quietest, but most compelling, voice in the room.

In 2014, Kane helped Gov. Pat McCrory’s office when negotiations over the sale of the Dix property to the city grew tense. Kane is friends with McCrory and through years of development work in the city had forged relationships with Raleigh leaders.

“He was able to work as an honest broker to keep the process moving forward,” says Lee Roberts, the state’s budget director at the time. “Without John’s constructive involvement, we’d probably still be trying to finalize the transaction.”

North Hills shopping complex (Photo/visitnorthhills.com)

‘Not a player’

Kane’s most high-profile deal is also his most unlikely. In 1997, two years before he bought North Hills Plaza and four years before he bought North Hills Mall, Kane seemed to cast doubt on his company’s potential to undertake what would become one of the Triangle’s most transformational projects.

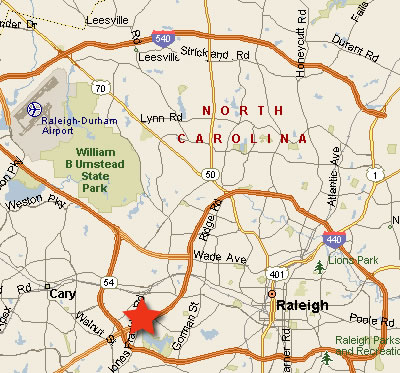

Kane had bought 55 acres of prime real estate on Walnut Street in Cary across from where the CrossRoads Ford dealership stands now. He hoped to build a shopping center like the one that sits there today.

But he was cautious.

“It is a little bit out of the ordinary for us. We’re probably more suited to doing smaller deals,” Kane told The N&O after buying the land. “We’re not trying to go be some player.”

Later that year, he sold the property without building on it. Kane said in a recent interview that he left the Cary market because of swelling anti-development sentiments. But 19 years ago, he told The N&O the Walnut Street project was too big of an undertaking for his company.

Kane Realty’s “concentration is on neighborhood center development and tenant leasing,” he said at the time. “We’re not prone to $50-million-to-$60-million developments.”

Couldn’t get a penny

Kane was in the process of redesigning North Hills Plaza, a neighborhood retail center on Six Forks Road in Raleigh, in 2000 when the owners of North Hills mall across the street approached him about buying the mall.

Kane only wanted the mall if he could redevelop it, and the mall’s contracts with its tenants left that prospect in question. Despite its decline as a destination, Kane says North Hills remained 92 percent occupied, and he didn’t want the headache of dealing with the tenants.

Kane feared JC Penney, which today remains in its original building, would fight his plans. “I told them, ‘We’ll buy it, but you gotta get an amendment with Penney so they can’t hold us up,’ ” he recalls.

Mall ownership accepted the terms, and Kane shifted to the pollution problem.

Tanks underneath a gas station on the property had leaked into the ground and spread 1,400 feet toward the Beltline. While the issue drove down the sale price, it made it hard for Kane to get funding to buy and redevelop the property.

“At the time, there wasn’t as much history and precedent of dealing with environmental issues, so people were scared to death of them,” Kane says. “We couldn’t get any financing. We couldn’t get 50 cents.”

So Kane partnered with Cherokee Investment Partners, a Raleigh business that cleans and redevelops polluted properties. Cherokee CEO Tom Darden says he believed in Kane, even if some plans seemed unusual.

“There were components that you had to scratch your head about,” Darden says. “At the time, if someone had told me that building a big, nice hotel there would be a synergistic use of the site … I wouldn’t have seen it.”

Jim Anthony, a real estate developer and broker with Colliers International, says Kane’s willingness to patiently craft innovative projects has made him the most dominant local developer of the last two decades.

“John, I think, does what he’s doing because he has a vision for land that’s a rare gift,” says Anthony, who’s known Kane since the late 1980s. “He can look at something and see what doesn’t exist but should or could. Then he brings the ingredients together to make it happen.”

Dorton Arena on the N.C. State Fairgrounds (Photo/TripAdvisor)

Relationships matter

If Kane’s vision is a gift, his patience is a calling.

Kane was born in Roxboro but raised mostly in Henderson, where his family moved when he was 4-years-old. He grew up going to church but says he didn’t start thinking about his place in life until shortly after he married Willa.

In both his public and private life, Kane says he tries to follow Jesus’ call for his followers to be humble, loving and forgiving.

The Kanes are founding members of Holy Trinity Anglican Church in Raleigh, created in 2004 by about 200 people who split from the national Episcopal church because they thought it was too liberal. They helped the church acquire land at the corner of Peace and Blount streets and build what would become the first new downtown church campus in decades.

These days, the Kanes are excited about a program they helped launch called New City Fellows, a leadership course that aims to help Christians apply their faith at work.

“Relationships really matter to John,” says Mike Smith, president of Kane Realty. “He’s so good at the follow-up and the check-up. He’s sincere; he’s authentic. He’s the real deal.”

One of the biggest struggles of Kane’s life came in 2002 upon learning that his chief financial officer had embezzled money – about $1.5 million, Kane later found out from state investigators – from the company.

The news was devastating. The Kanes were stunned and confused. Not only was Kane’s CFO a trusted employee, he was one of Kane’s best friends and the godfather of his second son, William.

“To be betrayed like that not just one time but over a period of 10 years … it’s pretty hurtful,” Kane says.

The N.C. Real Estate Commission in 2005 barred Kane from using his real estate sales license for at least six months. The CFO, Clifford “Mickey” Clark, was sentenced to 30 months in prison in 2007 after pleading guilty to a federal change of interstate transportation of stolen property. Real-estate license laws made Kane responsible for enforcing accounting systems that safeguard a company’s money.

Kane says he had a chance to pursue further charges against Clark and potentially recoup some of the money from his insurance company, but declined to do so.

“It was a forgiveness thing,” he said.

North Carolina Executive Mansion (Photo/Learn NC)

Pleasant adversary

Kane’s approach to relationships – “treat people the way you want to be treated” – has earned the respect of many of the people affected by his developments.

He hasn’t met all their requests over the years, says Patrick Martin, president of the Midtown Citizens Advisory Council, one of the resident-run councils that review local development proposals. But residents in the Midtown area appreciate that Kane is accessible, Martin says.

Kane shows up to CAC meetings and answers questions in person, something some developers send their attorneys to do, says Mack Paul, a local development attorney.

“He’s unique in letting himself be the face of his own company,” Paul says. “There are not many developers I work with that are willing to endure that.”

In 2000, as Kane revealed his redevelopment plans, Bert Rosefield formed a coalition of about 100 North Hills families to monitor the situation and protect their neighborhoods. Rosefield didn’t agree with all of Kane’s decisions; for one, Kane declined to keep a 100-foot tree buffer that some wanted to preserve.

Rosefield did, however, appreciate Kane’s willingness to listen and meet with concerned residents. In fact, he’d give Kane an “A” grade for responsiveness.

“I found him then to be a very pleasant and agreeable adversary,” Rosefield says. “He’s going to build what he envisions, but he’s willing to make small compromises which are very important to us. And he’s going to be a gentleman while he does it.”

Raleigh councilwoman Kay Crowder offered a similar review of Kane. Crowder, a tough critic of development, was considered the swing vote when Kane Realty sought to rezone its downtown property in preparation for The Dillon.

Crowder met with Kane over several months to discuss her desires to keep out rowdy bars, save the old brick warehouse façade and add more retail space on the ground floor – all of which Kane vowed to do.

“I found him very open to listening,” Crowder says. “He knows the difference between overbuilding and building responsibly. I found him tough but fair.”

Kane Realty is also working with the city and the Contemporary Art Museum of Raleigh, located across the street from The Dillon, to commission public art around the construction site.

“They don’t have to do that, but they care about the community,” said Gab Smith, CAM’s executive director. “John and his whole team are placemakers.”

A key voice

Kane isn’t done yet.

He plans to add a 31-story tower at North Hills, on the east side of Six Forks, which would be the second-tallest building by story in Raleigh. Over the next two years, the company hopes to build an $85 million to $100 million mixed-use project on the south side of Peace and West streets on the northern side of downtown.

It won’t be easy. The more developers seize Raleigh’s prime real estate, the more city leaders are scrutinizing them. Kane says he has good relationships with council members, none of whom are Republicans. Councilman Bonner Gaylord works for Kane Realty managing North Hills, so he’s required to recuse himself from votes related to Kane projects.

No matter. Kane – a longtime Republican booster who has welcomed George W. Bush, Rep. Paul Ryan, Sen. Marco Rubio and Sen. Richard Burr into his home – is well-regarded among many local Democrats because he’s willing to put party politics aside to push for initiatives he believes in.

In 2012, he broke with the local GOP to support an $810 million Wake schools bond referendum. And over the last couple years, Kane worked closely with county commissioners and about 70 other local stakeholders to craft the Wake Transit Plan.

The plan aims to bring bus service to every Wake town, dedicated bus lanes to Wake’s core and commuter rail between Garner and Durham. He co-chaired Moving Wake County Forward, which advocated for the sales-tax referendum that voters approved by a 52 to 47 percent margin in November.

Advocates say Kane’s help was key.

“If you look at North Hills on Six Forks Road, you can’t continue to just have an auto-centric mobile solution if you’re going to have that level of density. And he totally gets this,” says Sig Hutchinson, chairman of the Wake County commissioners.

“His voice, not only from the development side but from the Republican side, is critical,” Hutchinson says.

North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh (Photo/Google Maps)

No plans to retire

Kane spent a recent cold, rainy afternoon touring two towers he plans to open this year on the east side of North Hills.

First: the AC Hotel building, which he says will appeal to millennials by offering a sleek “minimalist” design. Dust and mud caked Kane’s work shoes as he hopped over puddles and walked through the exposed bottom floors.

Kane then made his way up the 12-story Allscripts building. From the top, he could see the construction crane five miles south at The Dillon site in downtown Raleigh. Company engineers walked over to the wall-to-ceiling windows, smiling and commenting on the span of the company’s real estate empire.

Kane said little, as he doesn’t show his emotions often.

He’ll grin or crack a joke while talking about deal-making and his experiences traveling the world. He smiles a lot, though, when he talks about Willa, their children and grandchildren. He tries to see or talk to his children at least once a week, even if it means getting up early to meet for coffee at a North Hills Starbucks.

And yet, Kane has no plans to retire or even slow down.

He says he has no “unfinished business” – no white whale project he’s dreamed about for years. He scoffs at the notion of building a legacy. And he denies that he’s a workaholic: “I’m not a deal junky,” he says.

He’s competitive, he admits, and he simply loves re-purposing things into projects that make the community better, the way he did when he bought a declining mall in North Raleigh and pushed the city in a new direction.