IF IT HADN’T HAPPENED the way it did, I would’ve sworn Robert Gipe had set it up.

IF IT HADN’T HAPPENED the way it did, I would’ve sworn Robert Gipe had set it up.

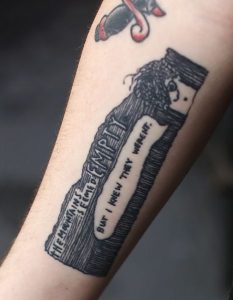

I was visiting him in Harlan, Kentucky, where he lives and teaches. We had planned to meet for lunch, but I was having a hard time raising him on the phone. So I found a pizza place called the Portal downtown and texted him to stop by. When he showed up a few minutes later, one of the servers hugged his neck. Her name is Devyn Creech. She has worked on three of the five Higher Ground plays Gipe has assembled over the years, built from the oral histories of people who live up here in coal country. Not only that, Devyn has a tattoo on the inside of her right forearm of a panel from Gipe’s illustrated novel “Trampoline.”

His student Devyn Creech sports a tattoo of one of Gipe’s drawings.

So the place I randomly picked for lunch turned out to be the same place where an employee had Gipe’s work sunk into her skin.

This revealed two true things.

One: Harlan, Kentucky, is a small town.

Two: Robert Gipe has touched a lot of people in it.

From his front porch, Gipe can see downtown Harlan spread out below.

The 1985 Wake Forest grad — his name rhymes with pipe, with a hard G out front — has spent most of his adult life building community art projects in this little pocket of eastern Kentucky. He’s 53 and has been up here more than 25 years, first with Appalshop — a nonprofit that blends art with activism — and then as director of the Appalachian Program at Southeast Kentucky Community and Technical College.

This part of the state is America in extreme. The mountains and rivers are some of the prettiest in the country. The people are some of the poorest. The coal industry supported thousands of families even as it wrecked the environment. Now even coal is fading and jobs are hard to come by. For young people, it can seem like the only way up is out. These are the things Gipe has nudged the community into talking about through the Higher Ground plays. They deal with ugliness — drug addiction, suicide, family fights over land and legacy. But they give a voice to all sides of the issues, and cut the pain with humor and music.

Gipe’s novel, “Trampoline,” is filled with his own illustrations.

The rest of the world is starting to notice. “Trampoline” — about a teenage girl named Dawn Jewell coming to terms with her life in coal country — won the Weatherford Award in fiction in 2015 for the best book about Appalachia. The New York Times came to Harlan a few years ago to write about the plays. Starting in September, the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York featured a scale model of the Higher Ground portable theater — a collection of seven stages and 150 bleacher seats that Gipe and his students hauled to towns around the region, so any community that wanted to could see a show.

“It compares favorably with, like, a U2 concert,” Gipe says.

Robert Gipe

He allows himself a little smile when he says that. He’s a natural storyteller with a dry Southern accent — in his mouth, the word riiiiiiight takes two or three seconds to make it all the way out. But he prefers to sit back and listen. In his community projects, students and townspeople make most of the decisions. Gipe guides, edits, keeps things on track. He wants the voice of the work to be theirs, not his.

“To let people realize their own experience is valid, and has a literary character, is deeply empowering,” says Maurice Manning, a poet and professor at Transylvania University in Lexington, who has known Gipe 20-some years. “To let people believe in themselves and hear their stories in their own words … there’s nothing elitist in his interest. He’s a real grassroots guy all the way around.”

“This place is rough, has had it rough, people are rough, have been treated rough, they’ve been knocked around,” Gipe says. “I love it here. I love working with the people here. And that was the thing. I never acted like I wanted to help anybody. I just wanted to be here.”

TO GET TO GIPE’S front door from the street, you have to climb 69 concrete steps. The view is worth the hike. You can see just about all of Harlan — population 1,700 or so — from Gipe’s front porch. If you watched “Justified,” the TV series set in Harlan that ran six years on FX, you saw a similar view at the end of the opening credits. The show — violent, funny, smart and Southern as hell — wasn’t shot in Harlan, but some of the writers and cast members came to town to understand the place better. (The Portal, where Gipe and I had lunch, turned up in the show as the restaurant where the bad guy played by Sam Elliott kept his ill-gotten cash in a basement safe. On TV, and in real life, the Portal used to be a bank.)

On a September night on his front porch, with cicadas trilling outside and Waylon Jennings on the stereo, Robert Gipe starts to tell his story.

He was born in Greensboro but grew up in Kingsport, Tennessee, where his father — who played basketball at the University of Tennessee — worked as a supervisor in a warehouse at Eastman Kodak’s giant factory. The plant made, among other things, the chemicals for Kodak film. “When anybody in the world took a photograph,” Gipe says, “an angel got its wings in Kingsport.”

But he also remembers the smell from the chemicals and the paper plant in town. He remembers a lot of people getting cancer. He remembers people trying to decide if the places that gave them a job and a wage were doing them more harm than good. Gipe drove a forklift at the factory in the summers and found that he liked the guys there. They took him frog gigging. They went out and shot groundhogs. A lot of the workers were from coal-mining towns in Kentucky and Virginia. He listened and developed an ear for the way they talked, and what they talked about.

Gipe reads notes from his students’ recordings of their family histories. “Between the mines and the curvy roads, there’s a lot of car wrecks, a lot of pain," he says. “People were trying to deal with it on their own, they’d act like it was a family failing, when really it was a system and community issue.”

By then, in the early ’80s, Gipe was a student at Wake Forest. He was awarded a Guy T. Carswell Scholarship and a National Merit Scholarship, and his mother went back to work as a registered nurse to cover the rest of the cost. He had always loved to write and draw, so he majored in English and minored in art history. Professor Emeritus of English Doyle Fosso (P ’81), a Shakespearean scholar and poet, inscribed a book of his poems to Gipe: To the regal sport from Kingsport.

Gipe helped start a student radio station, WAKE-AM, that broadcast on carrier current through the wires in the dorms. (These days, a student-run station called Wake Radio streams on the Internet.) He went to basketball games to see Muggsy Bogues (’87, P ’09) and Delaney Rudd (’85). On weekends, he and his buddies traveled the region to see bands. A lot of the new music he loved was coming from the South, and in his mind it connected with the storytellers at the factory back in Kingsport: “For me it kind of all went back to Jason and the Scorchers, R.E.M., this idea that there was a distinctly sort of Southern underground that was cool.”

After graduating summa cum laude from Wake, he went to the University of Massachusetts to get a master’s degree. His thesis was on outsider artists. He did some of his research at the library at East Tennessee State. One day he picked up a magazine he’d never seen before — Now & Then, a magazine about Appalachia. He ended up writing a sidebar to a piece in the magazine about volunteers who fought poverty in Appalachia in the ’60s. Somebody at Appalshop noticed the piece and invited him to apply for a job as marketing director. He started work at their office in Whitesburg, Kentucky, in 1989. He did a lot of work in schools, helping teachers and students tie their classwork to the culture of where they lived. He created a program called Where Art Meets Ed, a summer camp where teachers from different subjects learned how to teach art as part of their classes.

He left Appalshop in 1995 to move to Alabama, following the woman he was married to at the time. After two years there, Southeast Kentucky Community College brought him back to Kentucky to run the Appalachian Program and teach. He’s been there ever since.

His office in Cumberland, on the main campus, is covered floor to ceiling with posters for the projects he has created or supervised over the years. The five Higher Ground plays. The Crawdad music and arts festival. A conference called It’s Good To Be Young In The Mountains. A radio show and podcast called “Shew Buddy!,” which is roughly translated Eastern Kentucky for “Lord have mercy.”

A Charlie Brown head from a childhood costume sits on Gipe’s mantel at home.

He also has a shrine of sorts to “The Big Lebowski,” with bobbleheads of many of the main characters. They come from his friends. People see a bit of the Dude in Gipe. He doesn’t tote around a White Russian, but he’s got the same laid-back vibe. He’s 6-5 but it’s hard to tell unless he’s ducking through doorways. The rest of the time he’s hunched over or stretched out, usually wearing his daily uniform: jeans, black T-shirt, pen clipped to his collar.

Near Gipe’s Cumberland office is a community mosaic.

In the lobby outside his office at the Godbey Appalachian Center, his work shows on a bigger scale. There’s a giant mural of rural Kentucky life that an artist sketched out, then overlaid with a grid; people from the community then painted the grid squares to put the whole thing together. Another wall is covered with a peaceful mountain scene built from a mosaic of hand-shaped tiles. The tiles spell out quotes from some of the oral histories Gipe’s students collected. More than 200 people worked on the mosaic. They stamped the letters on the tiles with a garden-store kit.

The room behind the mosaic is the community college’s theater. Gipe hated theater as a kid. His main memory is playing the Woodsman in a version of “Snow White” and having to sing a song called “I’m a Terrible, Terrible, Terrible, Terrible Man.”

Which makes it all the stranger that theater is now what he’s most known for.

Gipe’s office is filled with student art and posters from his community projects. His computer screen’s logo refers to the project: It’s Good To Be Young In the Mountains.

THAT FIRST YEAR, 2005, the showstopping musical number featured a doctor handing out prescriptions while townspeople formed a bucket brigade to pass him cash. It was a bold move, especially since a real doctor in Harlan had just been arrested for overprescribing drugs. But Gipe and the cast — 85 people in all — had pushed to tell the truth the best way they knew how. On opening night, Gipe sweated as the cast started singing the song “Pain,” and the onstage doctor flung prescriptions into the air.

“It was amazing,” Gipe says. “You could hear people whispering in the audience. It hit like a hammer.”

That play was “Higher Ground,” which became the title for the series. The next play, “Playing With Fire,” centered on a daughter coming home from rehab — a twist on the biblical tale of the prodigal son. Then came “Talking Dirt,” about a young man who inherits land that a coal company wants to strip mine. The fourth play, “Foglights,” focused on layoffs in the coal business and the area’s foggy future. And “Find a Way” discussed the difficulty of talking about gay, lesbian and transgender issues.

But each play is also filled with subplots and digressions and jokes. As the publicity material for “Find a Way” says: “It is also about leveling with one another, dealing with economic and personal grief, lost dogs, homegrown tomatoes, telling one’s parents things they may not want to hear, and fending off packs of crazed coyotes with a flashlight and a radio.”

Professional playwrights and songwriters have worked with Gipe and the community to shape the plays, but with each version the pros have done less and less. The cast rewrites the scenes, reworks the songs and adds new material, all with the purpose of making the play feel authentic. The writers also make sure every side gets a say. Gipe knew “Talking Dirt” was going to be critical of the coal business, so “Playing With Fire” — the play before — made sure to put mining in a kinder light.

Gipe was worried that townspeople who worked on the production would pull their punches. There has been a controversy or two — a few cast members left “Find a Way” as it dug into sexuality issues — but for the most part, the cast goes deep. He remembers working on one scene where a bulldozer operator was arguing with his fiancée, an environmentalist, about the options they had as young people. A man watching the rehearsal — he hadn’t decided if he would be in the production — said the scene was weak. He talked about how parents weep at Harlan High’s graduation because they know their kids are leaving and not coming back: Nobody was offering me college scholarships. All I got was my mother crying. So when I got this job, I took it. The cast wrote his words straight into the scene.

Devyn Creech, the woman with the tattoo from back at the Portal, started working with Gipe on a play he did at her high school. She went to Morehead State to study theater, but Shakespeare didn’t move her like the stories of her own people did. So she came back home. She has worked on the last three Higher Ground plays, moving from actor to stage manager to writer to co-director. The grant money that Gipe gets to put on the plays allows him to pay Creech and some of the other people who work on the productions. He also sets aside some cash for child care and gas money. That way people can work on the play and not go in the hole.

Right now Creech, who’s 21, is working at the Portal and planning to go back to college. She has a better idea of what she wants to do: keep telling the stories of people in Harlan.

“A lot of us grow up not really liking this place much,” she says. “But when you work on these plays with Robert, and you learn about this place, it really becomes like a family. You see why you should love the place that you’re from.”

That same idea plays out in “Trampoline.”

Gipe tells the story of Dawn Jewell, a 15-year-old girl struggling with anger and confusion in fictional Canard County, a place much like Harlan. Her father is dead, her mother is a drug addict, and her brother beats on her all the time (although, to be fair, she beats on him even worse). Her grandmother is fighting the coal companies that want to mine the mountain where they live. Dawn accidentally, and reluctantly, steps into the battle. About her only solace is the voice of a young DJ on the local radio station.

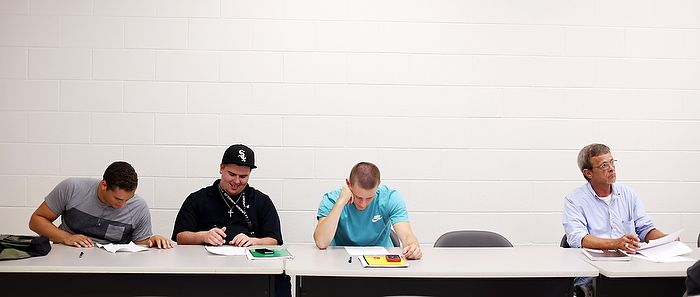

Students work on a quiz in Gipe’s class at the Southeast Kentucky Community & Technical College campus in Harlan.

Here’s a moment in Dawn’s voice from early in the book:

I was cold and filthy from sleeping at Houston’s. I wanted so to go in Mamaw’s and take a shower, but I did not want to have to talk enviro-fighter strategy with Mamaw. I wanted to go somewhere and be clean and beautiful. I wanted to wear a dress. I wanted to have my picture made. I wanted to rest my hand in the crooked elbow of a boy who loved me. I wanted our favorite song playing. I wanted my head on his shoulder.

Gipe salts the story with more than 200 of his drawings, but they don’t illustrate scenes that have already happened — they’re part of the flow of the storytelling. It’s like a TV character breaking the fourth wall and speaking directly to the audience.

Marianne Worthington, who teaches journalism and communication at the University of the Cumberlands in Williamsburg, serialized the first six chapters of “Trampoline” in the literary magazine Still: The Journal. She doesn’t remember ever seeing anything else quite like it.

“The story that Robert has written, it’s a messed-up family,” Worthington says. “And part of the reason they’re messed up is, they don’t have any money, they don’t have any education, and they’re at the mercy of the coal companies. That’s a real live thing that happens here every single day.”

This past summer, Southern Cultures magazine published the first chapter of Gipe’s follow-up novel, “Weedeater.” Gipe hopes to publish the full novel in 2018. It’s set in the same universe as “Trampoline,” and Dawn Jewell shows up right away. In an interview with author David Joy, Gipe described the themes in “Weedeater” as “the relevance of art, the futility of love, the possibility of saving somebody, and the importance of proper oil-gas ratios.”

Gipe’s students gather oral histories from their families. Those stories become the raw material for the community Higher Ground plays.

CLASS IS ABOUT TO START at the Southeast Kentucky campus in Harlan. Gipe teaches here and in Cumberland. On this night he has a dozen students, a mix of ages and races. Gipe is marveling at how many of his students have worked at Food City, the supermarket down the road. “Is it a requirement for this class that you have to work at Food City?” he says. It makes his students laugh.

Tonight he’s preparing his students to go interview family members. Those interviews become the oral histories that become the raw material for the Higher Ground plays. He has the students watch snippets of three Appalshop documentaries — one on a miner, one on an activist, one on a chairmaker. He asks the students to listen to what the subjects say, then come up with questions that might have produced those answers. Then the students call out the questions as Gipe writes them on the board.

He goes through each question, dividing them into categories. He erases the yes/no questions and the questions that might get short answers. He’s looking for long answers. He’s looking for stories.

“The way people do bridge-building, which we do constantly, changes the sense of the community,” he says.

“They know how to draw,” he says of the family members his students will interview. “They know how to make biscuits and gravy. They know how to change the oil in their vehicle. I want to know how they know all these things. I want to know what happened. What happened in your life?”

He gathers the remaining questions into themes. Questions that ask somebody to explain. Questions that ask somebody to describe. Questions that get people to talk about their feelings. Questions that wonder what happened next.

He edits and erases, narrowing the questions down to their core, and like a sculptor, without ever saying it, he reveals the questions behind all his own work. It is work built on a deep interest about how other people live, and a desire to hear their stories, and to help them tell those stories.

Gipe talks about his work as helping the people of Eastern Kentucky see their lives “in a whole new context. An elevated context.” He has spent all these years in one of the poorest places in America, and in that time he has revealed its wealth, not just to the outside world but to the people who live here.

Devyn Creech, the girl with the Gipe tattoo, picked one special panel from “Trampoline” to ink into her right forearm because it spoke to her. It is a single sentence:

The mountains seemed empty, but I knew they weren’t.

Tommy Tomlinson is a writer in Charlotte whose upcoming memoir is “The Elephant in the Room.” He was a longtime columnist for The Charlotte Observer and has also written for ESPN, Sports Illustrated, Forbes, Southern Living, Our State and many other publications. He is teaching his first journalism class at Wake Forest this semester.