SEATTLE — On the uplifting journey into the heart and soul of Killian Noe, you are forced to pull over now and then, just to catch your breath.

It’s the view of the community she shaped in downtown Seattle. It’s the strength of her belief that we are a better nation if we act as if we belong to one another.

It’s the doors she opens and the table she sets for guys like John Wilson.

Wilson was sleeping on a piece of cardboard in a Seattle parking lot in 2009 when the construction crew arrived on the downtown ridge above Lake Union.

He was 51 at the time, an ex-con still anchored to his addictions, eating far too often from a garbage can. The bushes, Wilson says, were “a safe haven when I was doing my incorrigible behavior,” but no escape from the Skil saws and hammers.

Exasperated, Wilson finally marched across Denny Way and asked the crew what the heck they were building.

The Recovery Café, he was told, which further infuriated him. “I didn’t need recovery stuff coming around me,” Wilson recalls. “I was a squatter, but I felt in some way insulted. It was my neighborhood. They came into my neighborhood.”

He’s a big man. He takes a deep breath. “Thank God.”

Why the change of heart? Because, Wilson explains, “I got to a place in my meaningless life where it became deplorable, and deplorable wasn’t working any more.”

Because he finally realized, as the lucky ones do, that he couldn’t make it alone.

Because he met Killian Noe.

“Killian is the picture of unconditional love,” Wilson says. “The expression of compassion. Of spirituality. There are a thousand words you can use to describe Killian. I’m damn near at the point of wanting to use ‘sainthood.’ ”

"Our willingness to fight for those suffering injustice grew out of our call to be in relationship with those suffering injustice. If we truly are growing in love with our neighbors who are suffering at the hands of unjust systems — if that love is deep enough and authentic enough — then FINDING OURSELVES OPPOSING THOSE UNJUST SYSTEMS WILL FOLLOW AS NATURALLY AS THE MORNING FOLLOWS THE NIGHT."

OR A DOZEN YEARS now, Recovery Café has been lunch counter, life raft and “community of radical hospitality” for those wrestling with addiction, homelessness and mental-health issues in Seattle.

OR A DOZEN YEARS now, Recovery Café has been lunch counter, life raft and “community of radical hospitality” for those wrestling with addiction, homelessness and mental-health issues in Seattle.

The café is solace and inspiration for 350 members who are otherwise abandoned when rents rise, minimum-wage jobs vanish, and cops and bus drivers are stationed at the front lines of the mental-health crisis.

“One way to change structures and systems that are leaving out large segments of the human family,” Killian says, “is to create what the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. called ‘beloved communities,’ communities that show what it looks like when those people aren’t left out.

“It’s a healing community for all of us.”

It’s the nexus of this story. But let’s take leave of the Emerald City for a moment to retrace the journey that brought Killian to the neighborhood.

Killian Noe has said, "All of us were created to be instruments of love."

She grew up in the Carolinas, the daughter of the Rev. Harold Killian, a Southern Baptist minister and 1944 Wake Forest graduate. “From early on,” Killian says, “I was programmed to think that was the best school in the world.”

When she arrived on campus as a junior, few things had as much impact as her conversations with a New Dorm (now Luter) housekeeper: “We struck up a friendship. When she took me to church with her, it awakened something in me: a social justice dimension in the Gospel that was more explicit than I remembered in the church of my childhood.”

If you also attended Wake in the ’70s, ponder that for a moment. Maybe you, too, were up early Sunday for the Wait Chapel processionals. Maybe you even caught a ride downtown to hear Dr. Ernest A. Fitzgerald rise to the pulpit at Centenary United Methodist.

But how many of us struck up a close friendship with the hospitality staff on the night shift? Which of us crossed the tracks and the racial lines to hear the Gospel at an African-American church?

That was Killian Noe’s nature. When court-ordered busing roiled her South Carolina high school, she devoted herself to building bridges between the old guard at the school and the strangers in the halls.

“My mom told me that as a little girl, I was always drawn to people who were different from me,” Killian says. “I think there was something deep in me that drew me to the places where people are suffering.”

That explains Tel Aviv and the Gaza Strip. Killian was just shy of 21 when she completed her course work at Wake Forest early and left in 1979 to spend three years in the Middle East. She mentored teenagers in Tel Aviv through the Journeymen program, then volunteered at Al-Ahli, the Gaza hospital run by the Anglican church.

Among the Palestinian refugees at Al-Ahli, Killian says, she fully grasped the wretched divide between those who have the chance to fulfill their potential and those who never do.

When she returned to the United States to attend Yale Divinity School, dividing her time between New Haven and Howard University in D.C., Killian recognized a similar despair in the men and women living on the city streets, hostage to their addiction or mental-health illness.

“We are connected to these people,” Killian says. “They are a part of us. We have to create narratives in our society in which their suffering is our concern, and ultimately, that their suffering is our suffering. The flip side of that? Their joys are our joys.”

She was wrestling with that on the morning in 1985 when the Rev. Gordon Cosby, founder of Church of the Saviour in Washington, D.C., preached that a city flush with marble monuments to former presidents also needed room at the inn for people who fell through the cracks.

“Something went straight through my heart,” Killian says. “I couldn’t stop crying. After the service, I found Gordon, and, with my puppy-red eyes, still feeling embarrassed, I said, ‘I think this is what I want to do with my life.’

“And Gordon, who’d heard it all before, who knew that when we have those impulses, we can push them back down and get on with what we’re doing, said, ‘There’s another young man about your age who has said the same thing to me. I want you to promise that before I see you again next Sunday, you will have gotten together with him.”

David Erickson was the young man’s name. They met in a park in the Adams Morgan neighborhood. After a brief lunch, Killian decided to quit her job and work full time on the launch of Samaritan Inns, sanctuaries for the homeless and addicted.

“I’ve never met someone who is so clear on that, that the world is not meant to be one where there are people on the inside and people on the outside,” says Kim Montroll, Killian’s longtime friend. “What do they say in the Beatitudes about the ‘pure of heart?’ ”

Killian has a liberating sense of purpose, even when the road ahead is obscure, Montroll says: “One-hundred percent clear? We’re lucky if we’re 50.1 percent clear. You’ll never have your act together. There’s no act to have together. Let’s get going. The world is hurting and divided.

“That’s how she lives.”

IT’S DIFFICULT TO GET Killian Noe alone at the Recovery Café. There’s always someone in her thoughts, and invariably someone in her arms.

Sometimes, it’s the woman whose father took to calling her “Little Criminal” at the age of 4 when her hospital bills for measles and spinal meningitis upended the family finances.

Sometimes it’s the guy who no longer believes he can fit his life story on the bottom of the pizza box that he flashes at passing cars on the Interstate-5 on-ramp.

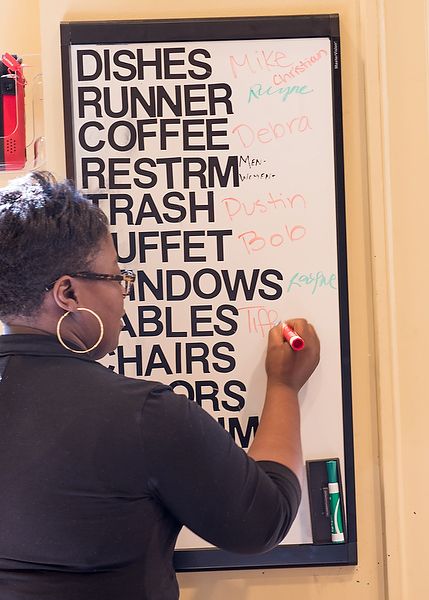

And sometimes it’s Tiffany Turner, the café’s 41-year-old floor manager, who has survived drug-addicted parents, domestic violence, alcohol and her late 20s, when she raised seven children, including her four siblings.

Turner believes Killian may be an angel. And the café? “The program isn’t perfect. Members relapse. Some even die. But the door is always open. The reason why the café is so strong, and so different, is that we have all suffered some kind of pain. The people behind the scenes, we all have a story. And we’re giving the love that we have received.”

When her husband, Bernie, relocated to Seattle in 1999, Killian left Samaritan Inns and Church of the Saviour, where, as she writes in “Descent into Love: How the Recovery Café Came to Be,” “I learned that by rigorously pursuing the inward journey — a deepening connection with our truest self, our God and with others in authentic community — we discover our outward journey, where our gifts connect with some need or suffering in the world.”

HE STARTED Recovery Café five years later at the edge of Seattle’s Belltown, then found more space for the lost on Denny Way even as the needs and suffering in the city grew more dramatic. Seattle’s homeless population surged 21 percent in 2015, and several shootings at the most notorious homeless camp, “The Jungle,” forced police to raze the tent city in October. Last February, the city was featured in “Chasing Heroin,” the PBS “Frontline” documentary on the opiate epidemic. King County’s 156-heroin-related deaths in 2014 have only added to the stigma of addiction.

HE STARTED Recovery Café five years later at the edge of Seattle’s Belltown, then found more space for the lost on Denny Way even as the needs and suffering in the city grew more dramatic. Seattle’s homeless population surged 21 percent in 2015, and several shootings at the most notorious homeless camp, “The Jungle,” forced police to raze the tent city in October. Last February, the city was featured in “Chasing Heroin,” the PBS “Frontline” documentary on the opiate epidemic. King County’s 156-heroin-related deaths in 2014 have only added to the stigma of addiction.

“Reasonable people become unreasonable when their kids pick up needles,” says David Coffey, the café’s executive director.

The café is open to anyone who has been clean and sober for 24 hours. Members must contribute in some way to the café’s operation. And they must remain committed to recovery circles, where they are held accountable and allow themselves to be deeply known.

“Live prayerfully. Show respect. Give and forgive. That’s what it comes down to at Recovery Café, and Killian creates the environment,” John Wilson says.

Wilson now has an apartment and a savings account at a local credit union. He moves furniture, sponsors several people in a 12-step program, and leads a Friday afternoon recovery circle at the café.

“When I come in there now, I still take the garbage out,” he says. “When new people coming off the streets, and off drugs and alcohol, see a familiar face from the streets, wiping tables and taking out the garbage that gives them some specter of what it can be and what they can be a part of.

“That’s what I had to do. I had to learn to be a part of.”

Don’t we all? “When you relapse on drugs or your mental health, it pulls you to the absolute edges, to this place of very painful isolation,” Killian says. “So, the invitation here is to maintain enough stability to stay grounded in community, grounded in relationships.”

Even when the times and culture celebrate the addictions we carry.

“I think wealth isolates us. Privilege isolates us,” Killian says. “And I think poverty and mental health and addiction hugely isolate us. What I always want to call people to is an authentic experience with authentic community, so that we can be known not just for our gifts but in our brokenness.”

She is blunt about the brokenness of this country’s politics. She doesn’t want Donald Trump to have the last word. “I think our nation’s soul is at risk,” Killian says, “when we push any group to the outside.”

She won’t abandon anyone to the refugee camp, the cardboard sheet, the lonely night shift in the New Dorm basement. She doesn’t separate the world into those who belong inside the circle of radical hospitality and those who don’t.

As she said at September’s Convocation for Wake Forest’s School of Divinity, “I don’t think it’s helpful for us to talk so much about God’s love. What is needed in these dangerously divisive times are communities in which we experience God’s love.”

That experience is now possible at Recovery Cafés in four other Washington cities and San Jose, California. “In our wildest dreams,” Killian says, “this model might spread like Habitat for Humanity.”

And John Wilson won’t be the last to say, “They came to my neighborhood. Thank God.”

Steve Duin is The (Portland) Oregonian’s Metro columnist. He is the author/co-author of six books, including “Comics: Between the Panels,” a history of comics; “Father Time,” a collection of his columns on family and fatherhood; and a graphic novel, “Oil and Water.”