necessarily be where you’d expect to find the home of a Deacon basketball legend, but the tiny community of Timberlake, North Carolina, is closer to the heart of Wake Forest than it seems.

Take a right at the general store/pharmacy and a meandering road leads you through Person County countryside lush with green pines, pink crape myrtles and whitewashed fences. A few turns later and the pavement ends at a bumpy gravel road, dotted with puddles from recent rain, that slinks through woods where deer, wild turkeys and a gray tabby named Emerson Rogers roam at will.

As the trees thin, a spacious house — part chalet, part log cabin — comes into view on the left, set back on a sprawling green lawn. It has vast picture windows that bring the outdoors in, vaulted ceilings, a screened-in porch, assorted outbuildings and garages. And where most homes would have stairs, this one has wheelchair-accessible ramps.

This secluded spot, far from arenas in Denver or Los Angeles yet not too far from Joel Coliseum, far from the spotlight but just 30 minutes from Durham where he grew up, is where Rodney Rogers (’94) has found a measure of privacy and peace.

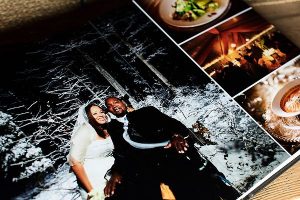

Removed from the public eye but surrounded by the great outdoors he loves, Rodney and his wife, Faye, take life one day at a time since a tragic dirtbiking accident left him paralyzed from the shoulders down.

‘He is totally 100 percent my soulmate,’ says Faye. ‘He has not changed through adversity.’

XXXXX

I’ve traveled to Timberlake with Rodney’s longtime friend and adviser, Jody Puckett (’70, P ’00), who has made the trip many times. We come bearing Mountain Fried Chicken, at Rodney’s request, and find him in the great room wearing a black Wake Forest T-shirt and black sweatpants.

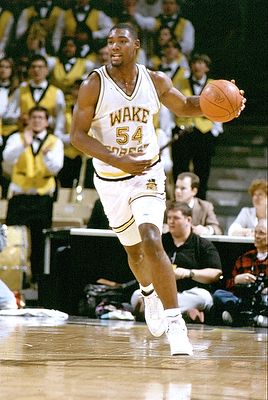

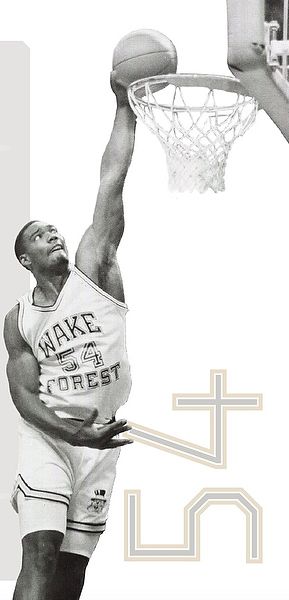

He’s watching highlight reels on a ceiling-high television, and as he analyzes plays and second-guesses strategy, it’s apparent that while his body has been rendered motionless, his mind is as active as ever. At 45, No. 54 remains an imposing figure. His 6-foot-7-inch body fills a motorized wheelchair. He breathes through a tube inserted into his windpipe, and round-the-clock caregivers are always nearby.

Hanging from rafters in the great room, where Rodney spends much of his time, are colorful tributes to his career: framed jerseys representing Wake Forest and the seven professional teams for which he played: the Denver Nuggets, Los Angeles Clippers, Phoenix Suns, Boston Celtics, New Jersey Nets, New Orleans Hornets and Philadelphia 76ers.

To his left is a black and gold Wake Forest wall showcasing basketball memorabilia including a plaque containing a section of the parquet floor from The Joel. Also there is the No. 1 football jersey he wore when he “opened the gate” at the Wake-Elon game in September 2009. On the hearth in front of him are trophies — his 2000 National Basketball Association Sixth Man Award and an Emmy for a documentary film about his life. To his right are framed, signed jerseys of NBA legend Julius Erving and NFL San Francisco 49ers star Jerry Rice.

A collection of No. 54 jerseys hangs from the rafters in the Rogers’ home.

“Well, I’m doing pretty good, taking it one day at a time and trying to get things done,” Rodney tells me. “I get upset at stuff sometimes. I made a mistake that I shouldn’t have made. I had to get a grip on it at first. I didn’t even want to go outside, didn’t want to do anything. But like my wife said, ‘Baby, this is our life now.’ You just deal with it and move forward. That’s what I did.”

On that Friday after Thanksgiving in 2008 the ground was wet and the mud was slick. Faye, then his fiancée, begged him not to go dirtbiking. Rodney was an experienced rider but on that day he hit a ditch and flew over the handlebars, landing flat on his back. He yelled to his friend that he’d hurt his neck and couldn’t feel anything.

“For the first 30 days I cried; I didn’t even bathe,” says Faye, who married Rodney in 2010 beneath a huge tent on their front lawn. At times the magnitude of how their lives had changed threatened to break their fighting spirit, but she knew they had the strength to survive; they just had to find it together. She has been a godsend, says former Wake Forest Head Coach Dave Odom, who recruited and signed Rodney, and she deserves considerable credit for holding their lives together. “In life when one thing is taken away, another is given,” Odom says.

“For the first 30 days I cried; I didn’t even bathe,” says Faye, who married Rodney in 2010 beneath a huge tent on their front lawn. At times the magnitude of how their lives had changed threatened to break their fighting spirit, but she knew they had the strength to survive; they just had to find it together. She has been a godsend, says former Wake Forest Head Coach Dave Odom, who recruited and signed Rodney, and she deserves considerable credit for holding their lives together. “In life when one thing is taken away, another is given,” Odom says.

After his injury doctors gave Rodney a 50-50 chance for survival, and to this day he courageously beats those odds. “He is totally 100 percent my soulmate,” says Faye. “He has not changed through adversity. He is giving, considerate, thoughtful of people, me and our family. He is the same, only still.”

OOOOO

odney did not have an easy childhood, but he never used that as an excuse to misbehave or get in trouble, says Jenny Robinson Puckett (’71, P ’00), Jody’s wife, who was Rodney’s Spanish tutor at Wake Forest. “That wouldn’t have occurred to him. Some people just have it. It’s an ‘it’ factor I can’t put my finger on.”

But then, just like that, she does. “ … the things he did, large and small … there was always this thread of grace through Rodney,” she says, her voice cracking with emotion. “Because without that he would have, by now, given into despair; without that thread of grace and courage, he might not be alive.”

The mortal tapestry that is Rodney Rogers is woven from threads of grace: character, courage, kindness, determination, humility and compassion. His power isn’t just a physical presence but a spiritual one. He is a man who, despite overwhelming personal challenges, maintains his own courage, hope and dignity while inspiring others to find theirs.

“My opinion of him has always been very high because from the first time I met Rodney the difference between him and many other students, or players or people, was that he had such an attitude of humility and respect for having landed at Wake Forest, and it was obvious he wanted to do his very best in return.”

When Rodney was young his mother was critically injured in a car accident and required extensive longterm care. His father left the family and died when his son was a boy. Rodney, his sister and brothers grew up in Durham’s McDougald Terrace housing project. When Rodney broke his leg playing football, he hobbled to school on crutches because he had no other way to get there. His stepfather, the only man Rodney called “Dad,” died in 1990. Rodney was divorced from his first wife, with whom he had three children: Roddreka, Rydeiah and Rodney Rodgers II.

Despite an unsettled home life, he excelled as an athlete. Blessed with a physique that former Wake Forest teammate Randolph Childress (’95) describes as “touched by God,” Rodney had the body to play basketball and the mind to understand it. At Hillside High School he was dubbed “The Durham Bull.” The parents of his best friend, Nathaniel Brooks Jr., took note of his personal struggles and determination there. One day Mr. Brooks, a masonry contractor who had coached one of Rodney’s youth teams, told him, “Get your clothes. You’re coming to live with us.”

The Brooks family valued hard work and education. “They instilled their ways into me and how I needed to be — make the bed up, say scripture at the front of the church,” Rodney says. He credits the Brookses with pointing him in the direction of Wake Forest. In yet another tragic event in Rodney’s life, Nathaniel Jr. died in a motorcycle crash in August 2008 — just months before his own accident.

“Rodney was so much of a puppy dog, and I say that in the kindest way. You wanted to hold him and pat his head. He would do anything you wanted him to do. Extra tutoring? ‘Where do I go?’ He wanted to become part of the greater Wake Forest community, and he did. He earned the respect and love of students, faculty and staff.”

XXXXX

odney the gifted athlete could have gone to many a school, but he wanted to compete in the Atlantic Coast Conference. He was committed to his education and chose Wake Forest; it was small, and he knew he would get the attention he needed to excel on and off the court. Once he committed, he never wavered. “I wasn’t worried about basketball,” he says. “God gave me the talent so all I had to do was work hard and show the coaches I could play. But I had to get my grades first before I could do anything else.”

odney the gifted athlete could have gone to many a school, but he wanted to compete in the Atlantic Coast Conference. He was committed to his education and chose Wake Forest; it was small, and he knew he would get the attention he needed to excel on and off the court. Once he committed, he never wavered. “I wasn’t worried about basketball,” he says. “God gave me the talent so all I had to do was work hard and show the coaches I could play. But I had to get my grades first before I could do anything else.”

Jody, a retired businessman who worked in the athletic department for 16 years as a basketball trainer and academic adviser, describes Rodney as the biggest, most-gifted athlete he’d seen at Wake Forest in 50 years — and also one of the kindest and hardest-working. He remembers when Rodney and other student-athletes had dinner at the Puckett home before a tutoring session. After thanking Jenny for the food, several in the group headed to the den. But not Rodney. He stayed behind to help clear the table and load the dishwasher.

“It was as if he were saying, ‘I don’t take this meal for granted, I’m thankful that you went to the trouble,’ ” says Jenny. “And he was always so kind in return to any kindness you showed him.” Rodney often let his teammates know how to show respect to a coach, to a tutor … that it was not just the words you said, but the way you said them, Jenny says. “I heard him correct a couple of people in the tutoring group, and if they were late, he took that up with them. And the people he was talking to understood it was appropriate for him to call their attention to it. He got automatic respect. He was sort of the unspoken leader of the group.”

One evening before Wake was to play Duke, Rodney and Jenny were preparing for a Spanish exam while Jody tidied up the kitchen. Coach Odom had a mandatory meeting the night before each game, and Jody, who was responsible for getting Rodney back to campus on time, realized they were about to be late. “I ran into the dining room and pointed out the time,” he says. “Rodney looked at me and said, matter-of-factly, ‘Coach Odom knows where I am,’ and he kept right on working. We beat Duke the next day and Rodney did well on his Spanish exam.”

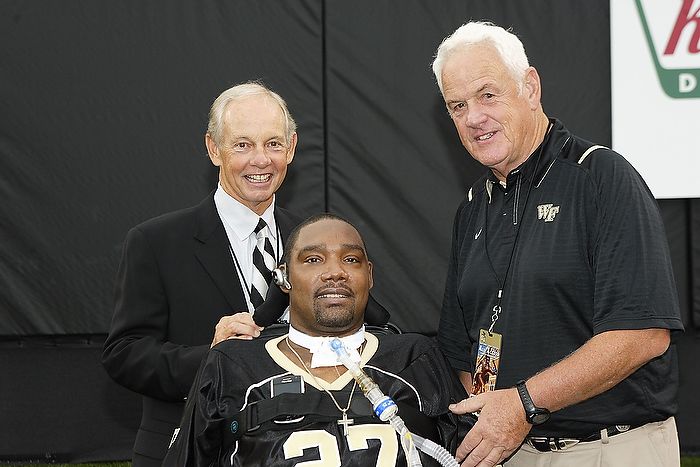

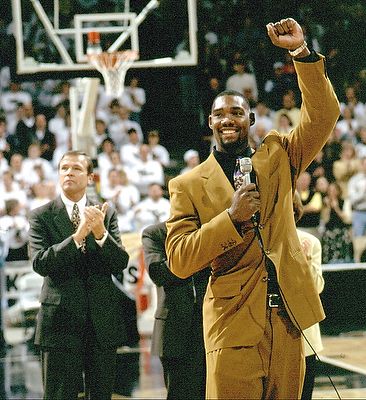

Rodney with Dave Odom (left) and Bill Faircloth (’64)<br /> (Brian Westerholt/Sports on Film)

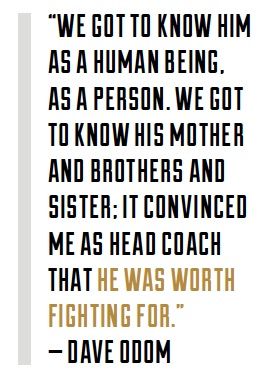

When Odom became head coach in 1989, he asked Jerry Wainwright, an assistant coach, if there were players whom the previous staff had been recruiting they should follow up on. The first name out of Wainwright’s mouth was Rodney Rogers. There was this kid in Duke’s backyard, and Carolina’s and N.C. State’s, and he was big and strong; he played all the sports and was the best in all of them, but basketball was his love. “No matter where you were as a basketball coach in America, you knew about Rodney Rogers,” Odom says.

As Wake coaches got to know Rodney better, they moved beyond his scoring averages, his rebounds and assists, beyond how fast he could throw a baseball or how far he could toss a football. “We got to know him as a human being, as a person,” Odom says. “We got to know his mother and brothers and sister; it convinced me as head coach that he was worth fighting for.”

The stars aligned and Rodney committed to Wake Forest in 1990. “From a basketball standpoint he was a huge first step for us,” says Odom. “I have said on numerous occasions in my term as head coach, Rodney Rogers was our most important recruit, simply because prior to him, there was nothing to indicate Wake Forest was serious about championships. When we signed him, it kind of opened the door and cleared the air that Wake Forest was indeed serious. The next guy we signed was Randolph. Rodney was the beginning.”

Randolph Childress (’95)<br /> (Brian Westerholt/Sports on Film)

A Deacon legend in his own right who last year was promoted to associate head basketball coach, Childress and Rodney entered the program together; they still have each other’s backs. “I don’t know if I can even put into words what he means to me; I don’t think he understands it,” Childress says, emotionally. “Rodney Rogers is the reason I’m at Wake Forest.”

Childress wanted to play in either the Big East or ACC and made only two official visits: to Seton Hall and Wake. When he found out Rodney was coming to Winston-Salem it made his decision easy. “He was always giving, always a team guy … he wasn’t intimidating or a bully, just as humble as if he were 160 pounds instead of 260. That’s the charisma he had about him; he was an imposing guy, but he was one of the guys. He had a magnetic personality about him.”

He relishes the story of a conditioning workout freshman year when one player was late for the morning run; if he didn’t show, the whole team would have to do a makeup run. Rodney took charge, directing a teammate to go fetch the offender. No. 54 then made it clear to the late arrival, “We’re going to run.” Says Childress, “He never lifted weights in his life but he was as strong as a Durham Bull. Everyone watched and kind of fell in line. And coach blew the whistle, and we ran.”

Rodney was not the kind of athlete who needed a lot of encouragement, Odom points out. He “brought it” every day and expected others to do the same. “The great ones are usually like that,” he says. But No. 54 had a way of inspiring those who might not have brought as much. “The thing about Rodney was that, in his own way, he realized he needed others because it was the consummate team game; he couldn’t go out and do it by himself. That was his way of saying, ‘I need you. You help the team so that we can be the best we can be.’ ”

Childress, 1995 ACC Tournament MVP who secured his own place in Deacon history with “the shot” that beat North Carolina in overtime, acknowledges he talked a lot of trash during Rodney’s reign. But he had a 6-foot-7 safety net. “I had No. 54 behind me. That gave me the ability to be as comfortable and confident as I was because I knew I had the big guy behind me.”

“I was in Italy, and Rodney was on the opposite side of the world. Coach Odom would call and say, ‘Call Rodney. He needs to hear from you.’ So I’d call him and he wouldn’t answer, and I’d call him and he wouldn’t answer. So I left a message and said, ‘Listen, I’m six hours ahead, and I will call your ass all night until you pick up the phone.’ And the minute I left that voice mail my phone rang. If he heard that life was dealing me a challenge … he would let me know, like he always has, ‘I got your back, and I’m here.’ Every time we talk the conversation reverts back to how he can help me.”

Rodney left college a year early and was drafted by the Denver Nuggets in 1993, but he returned to campus that summer. Working with Jenny, he completed a Spanish literature class to fulfill his foreign language requirement and bring him one step closer to getting his degree, which he still intends to do. During that period Father’s Day came around; they talked about fathers and the fact that Rodney had barely known his. Jenny didn’t think anything more about it until a few days later when he told her he had gone home to Durham and asked his mother where his dad was buried. He was going to visit his dad’s grave to honor him.

“Having grown up without a father, Rodney himself grew to be a father figure,” says Jenny. “It was a natural role without being too sugary. ‘I’m going to be strong; let me help you do the same because we’ve got to get going here.’ It was just inborn in him.”

OOOOO

![]()

n the Rogers’ Timberlake home is a piece of artwork that reflects the couple’s shared outlook. It reads, “The future is just a collection of successive nows.”

Their successive “nows” focus on mutual support and well-being, as well as fulfilling Rodney’s mission to spread the message of staying positive while living life as a quadriplegic. They stay involved in the community through the Rodney Rogers Foundation, a nonprofit they created to encourage those with spinal cord injuries to pursue personal growth and individual virtue.

The foundation also sponsors events in Rodney’s childhood neighborhood, McDougald Terrace, such as book drives to encourage youngsters to read, and donates school supplies so students have no excuse to neglect homework. At Thanksgiving the foundation provides turkeys and extra food for families; at Christmas children receive toys, and those with the best report cards get bicycles. These are the occasions that Rodney, a natural people-person, enjoys most. “I try to be a help because when I was growing up I didn’t have that kind of help. It makes me feel good to sit back and watch them smile because kids run and grab a bag, they hug me and tell me thanks.

Alumnus Jody Puckett visits with Rodney at his Timberlake home. Jody and his wife, alumna Jenny Puckett, have been longtime friends and mentors to Rodney.

“The most open I ever saw (former Wake basketball coach) Jeff Bzdelik was when I took Jeff to meet Rodney. Jeff had coached the Denver Nuggets, and those two just connected. They looked over NBA playbooks and talked basketball for a good two hours.”

“I had always been a shy, humble kid,” he says. “Even when I had the name that I got, superstar Rodney Rogers, it never dawned on me, I never let it get to me. I just wanted to play ball and win. If I had a chance to take time out to talk to you or sign an autograph, that’s what I did. A lot of athletes, if kids try to come over, they haven’t got time … I saw a lot of guys who wouldn’t talk to fans. I didn’t ever want that; I wanted to come out and be a winner. I wanted to make the fans happy because the fans make me who I am.”

Last summer Rodney was an honored guest at the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) Top 100 Camp in New Jersey, where he gave a motivational talk and shared life lessons with the league’s rising stars. The NBPA honored his commitment to living life to the fullest by presenting a camper with the first Rodney Rogers Courage Award.

Rodney gives a motivational talk to young athletes at the National Basketball Players Association Top 100 camp last June.<br /> (Courtesy of the NBPA's Top 100 Camp)

“Oftentimes in life we encounter difficult times, and the true measure of a man is how you deal with those difficult times and how you continue to move forward,” said Purvis Short, NBPA director of player programs, at the award presentation. “None of us have had a situation as difficult as what Rodney’s been going through. He’s never wavered, his courage has always been outstanding. He’s really been a true example of what it means to face life’s most difficult challenge, and continue to try to move forward and to give back.”

“I’m still here for a reason. I think that’s one of the reasons God kept me here. I’m still talking and praying and reading the Bible and trying to figure out what’s his real reason. Got to talk it out with him and see where it leads.”<br /> — RODNEY ROGERS (’94)

XXXXX

hildress was playing ball in Italy when he got the call from Coach Odom about Rodney’s accident. “I didn’t say a word; I just broke down and hung up the phone.” Weeks later he visited Rodney in the Atlanta rehabilitation center where he had been transported from a Durham hospital. “The first couple of hours we just watched him sleep. He was battling. Tubes everywhere. He wakes up and I say, ‘Hey, big guy.’ And instantly the conversation goes to me. ‘How’s your son? How’s your career?’ The entire conversation became about me. He’s the strongest person I’ve ever met. I used to say that from a physical standpoint. Now I say it from a mental standpoint.

hildress was playing ball in Italy when he got the call from Coach Odom about Rodney’s accident. “I didn’t say a word; I just broke down and hung up the phone.” Weeks later he visited Rodney in the Atlanta rehabilitation center where he had been transported from a Durham hospital. “The first couple of hours we just watched him sleep. He was battling. Tubes everywhere. He wakes up and I say, ‘Hey, big guy.’ And instantly the conversation goes to me. ‘How’s your son? How’s your career?’ The entire conversation became about me. He’s the strongest person I’ve ever met. I used to say that from a physical standpoint. Now I say it from a mental standpoint.

“My kids need to know who Rodney Rogers is,” adds Childress, whose son Brandon is a freshman on the Wake team. “Younger players need to meet him because I don’t think they understand who or how dominant he was. Over the years, as the coaching staff changes, his impact will not change at this University. That will last forever.”

Odom, who searches for a word to describe his drive down to Durham after Rodney’s accident — then chooses “surreal” — says that if Rodney’s life were divided into two chapters, one before the accident and one after, when you compared the two you’d see human traits that were in both. “But they’re more apparent in the second chapter, because that’s when most people who have less spiritual attributes come apart and give up. He has not done that.”

Wake Forest retired Rodney's No. 54 jersey in 1996.

OOOOO

![]() n the woods of Person County, Rodney’s voice is fading, and out on the front porch Emerson Rogers is nudging an empty Friskies can. It’s time to say our goodbyes. But not before we step out back for a quick tour of Rodney and Faye’s impressive RV — black and tan but close enough to call black and gold — specially outfitted to make his travel more comfortable.

n the woods of Person County, Rodney’s voice is fading, and out on the front porch Emerson Rogers is nudging an empty Friskies can. It’s time to say our goodbyes. But not before we step out back for a quick tour of Rodney and Faye’s impressive RV — black and tan but close enough to call black and gold — specially outfitted to make his travel more comfortable.

Rodney tells us how much he misses going to NASCAR races, tinkering with cars and driving big trucks (if you didn’t know, he started a trucking company and was also a heavy equipment operator for the city of Durham after he retired from the NBA in 2005). He is energized by the outdoors and prays that God will one day let him go riding and hunting again.

Rodney, who always loved to tinker with cars and drive heavy equipment, is proud of the large RV parked in his backyard.

I ask Rodney to name the best player in the NBA. Without hesitation, in as robust a voice as he can muster, he shouts, “Me!” And there is that broad smile I remember from his Wake years.

Cherin Poovey with Rodney Rogers

“We want to see you back on campus again soon,” I say. “Maybe I’ll get down for a game this season,” he replies. “Maybe I’ll even walk in.”

Through many dangers, toils and snares, Rodney Rogers has persevered. Fortified by threads of grace, he takes life’s court each day to face his toughest opponent of all.

“The fortunes of his life have taken a turn that would have done most of us in by now,” says Odom. “He continues to not only fight it, but perhaps win, the battle.”

He is the same, only still.

RODNEY’S REIGN

WFU (1990-93), NBA (1993-2005)

1991 – ACC Rookie of the Year

1991 – ACC Rookie of the Year

1992-93 – Two-time first-team All-ACC

1993 – ACC Player of the Year, consensus second-team All-American

1991-93 – Led Wake Forest to three NCAA tournament appearances including a Sweet Sixteen berth in 1993

1993 – Ninth pick overall in NBA Draft by the Denver Nuggets

1996 – No. 54 jersey retired at Wake Forest

2000 – NBA Sixth Man of the Year Award with Phoenix Suns

2003 – Played in NBA finals with New Jersey Nets

2004 – Inducted into Wake Forest Sports Hall of Fame

2005 – Retired from NBA

2014 – Inducted into North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame

12 seasons with seven NBA teams:

Denver Nuggets

Los Angeles Clippers

Phoenix Suns

Boston Celtics

New Jersey Nets

New Orleans Hornets

Philadelphia 76ers

CAREER STATS

Average points per game:

Wake Forest, 19.3

NBA, 10.9

Average rebounds per game:

Wake Forest, 7.9

NBA, 4.5