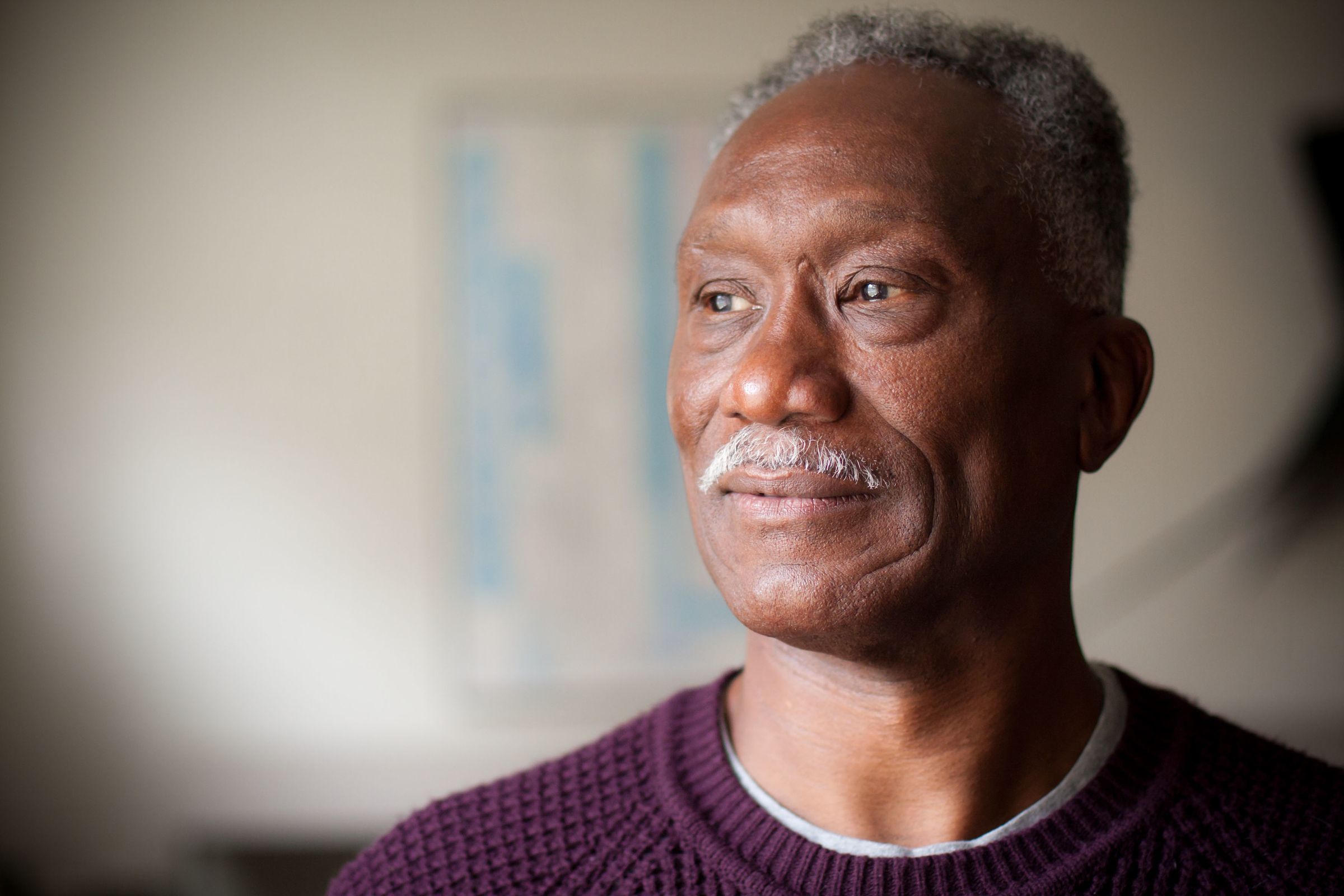

Herman Eure (Ph.D. ’74) never expected that studying parasites would lead to receiving Wake Forest’s highest honor, the Medallion of Merit.

And in a way, it didn’t. His research is part of the picture, but the trails that Eure, 70, has blazed spread out in many directions. What led to the retired biologist’s medal, awarded Feb. 16, was his commitment to the University and to mentoring and supporting students — especially African-Americans when black academic role models were in short supply.

"For me being a college professor is a whole lot more than being in the classroom and doing research. You’re a mother, a father, a coach, a mentor, a cajoler, the person who has to crack the whip."

Eure was Wake Forest’s first full-time black graduate student in 1969, its first black doctoral recipient on the Reynolda Campus and its first black full-time faculty member. With an unflappable demeanor, he overcame others’ doubts and persuaded Wake Forest to create the Office of Minority Affairs (now the Intercultural Center) in 1978, at a time when many universities were just beginning to recognize the unique needs of minority students.

His successful, rewarding career as a parasitologist, researcher, teacher and administrator included serving as chairman of the biology department and associate dean of the College at Wake Forest. He retired in 2013 to travel, volunteer and spend time with his family – his wife, Kelli Sapp (MS ’93), who teaches biology at High Point University, two children and seven grandchildren.

“I never expected to win the Medallion of Merit,” Eure said. “In some ways it’s kind of embarrassing to be given an award for doing something that you knew you should be doing anyway. For me being a college professor is a whole lot more than being in the classroom and doing research. You’re a mother, a father, a coach, a mentor, a cajoler, the person who has to crack the whip. You’re all those things.”

Eure has been a mentor to many students including Randolph Childress ('95), associate head basketball coach.

Eure was born the seventh of 10 children to parents whose formal education ended at fifth and seventh grades. But his parents raised their children in the small northeastern North Carolina town of Corapeake, in Gates County, with a relentless message — that they could succeed at anything they wanted to do in this world. Anything.

“I was never afraid,” said Eure (he adopted the more common pronunciation of “YOU-ree,” though back home it’s pronounced “Yewr”). “People used to say, ‘He’s cocky.’ It wasn’t cockiness; it was confidence. My father would make us prepare. If we were digging a ditch, do it the right way or don’t do it.”

Eure excelled early at math and science as well as football, basketball and track. He graduated as valedictorian and a student leader at his segregated high school and studied science at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, a historically black college where he was a leader once again. His mentors there urged him to apply for graduate school.

Among Herman Eure’s honors:

2017: Wake Forest Medallion of Merit

2011: Donald O. Schoonmaker Faculty Award for Community Service

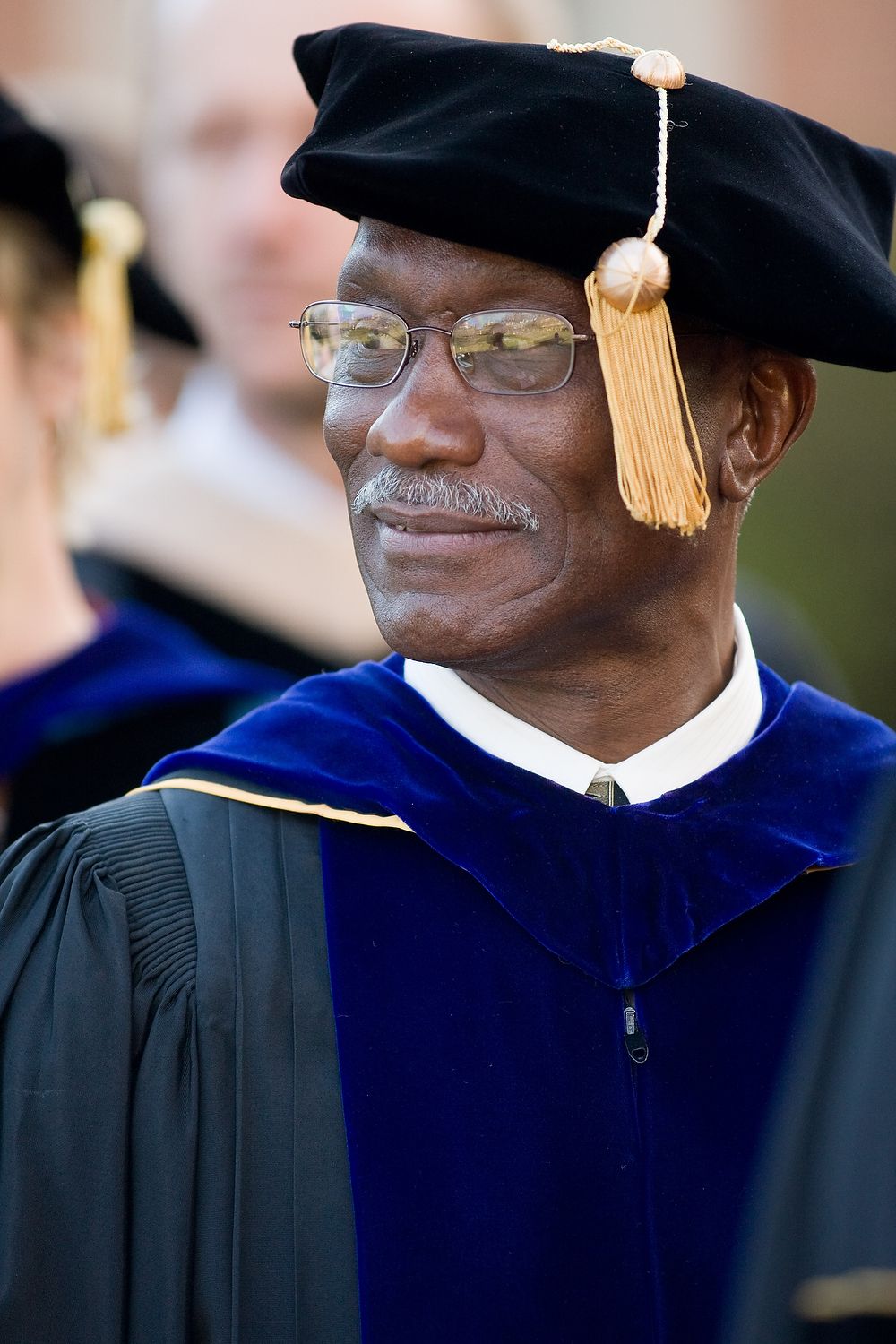

2008: First faculty member to deliver Founders' Day address

2001: Jon Reinhardt Award for Distinguished Teaching

1990: The inaugural Trident Professor Award from the Gamma Kappa Chapter of Delta Delta Delta

Gerald Esch (P ’84), who was chairman of the Wake Forest biology department’s graduate committee, said he told the young black man who showed up at his door in 1969 that the department had no money left to pay him as a teaching assistant, which most graduate students needed to pay their bills. “He looked at me kind of funny and said he didn’t need any money. He said, ‘I have a Ford Foundation Fellowship for five years.’ ”

Eure wanted to be a parasitologist, and that was Esch’s specialty, too. With Esch’s help, Eure went straight to doctoral study, skipping a master’s degree but taking all the same courses for both degrees. Esch helped Eure and another student do research at the Savannah River Ecology Laboratory at the nuclear site in Aiken, South Carolina. Eure studied parasites in largemouth bass.

As Wake’s only black graduate student, Eure said he encountered some bias, more often from workers who thought he should stick to his own kind. Students and faculty would ask whether he played basketball or football, assuming a black student must be an athlete. He experienced nothing but support in the biology department. “After my first year there, no one doubted that I could do the work,” Eure said.

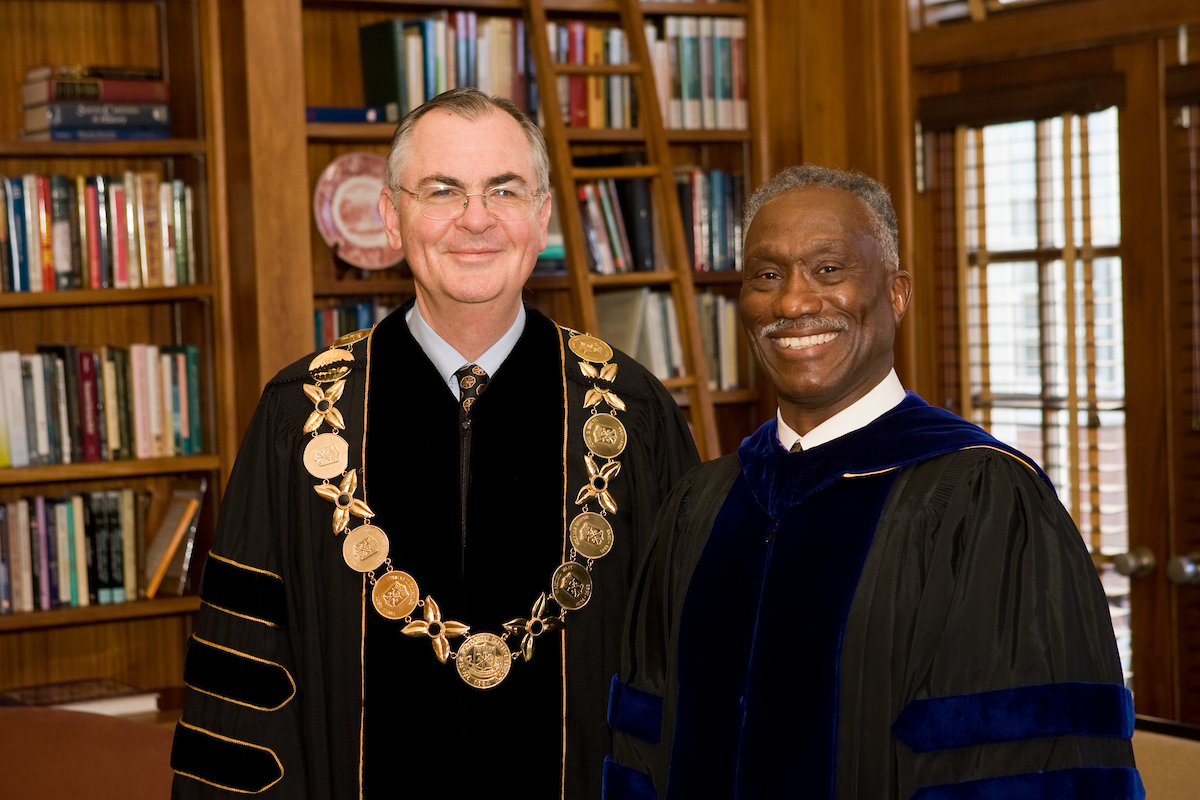

Professor Herman Eure and President Nathan Hatch prior to Eure's address at Founders' Day Convocation in 2008.

When Eure finished his doctorate in 1974, he had faculty job offers elsewhere, but he saw what was possible at Wake Forest. He stayed because of three men committed to progress: Provost Ed Wilson (’43), President James R. Scales and Dean of the College Tom Mullen (P’ 85, ’88).

Mullen said he worked hard to recruit Eure.

“I was most favorably impressed the first time I met him,” Mullen said. “For one thing, here is a man of great emotional balance and maturity.”

Eure always worked hard, was a gifted teacher and successfully recruited many sought-after black students, Mullen said.

Eure was surprised by his experiences as the first black faculty member. (The late Dolly McPherson arrived in the English department the same year). He knew he could mentor black students, but he found his greatest immediate impact was on white students, most of them facing a black teacher for the first time.

“I was most favorably impressed the first time I met him,” said former Dean of the College Tom Mullen. “For one thing, here is a man of great emotional balance and maturity.”<br /> <br />

“I was 27 years old, with the big Afro, the bell-bottom pants,” Eure said. “There were some kids who didn’t quite know how to take me, thought I was biased. I said, ‘If you do the work, you can be green. You’ll get the grade that you earn.’ ”

Minority enrollment data at Wake Forest wasn’t available for 1974, but minority students have increased from 11 percent of the 3,624 undergraduates in 1992 to 29 percent this academic year, with black students accounting for 6.5 percent of the 4,955 students enrolled in fall 2016, according to the Office of Admissions. Black representation was 3.3 percent of the 451 faculty members in 2015, the most recent year available.

Eure instilled confidence in his students while accepting no excuses for not trying. “You may not be able to do something as well as someone else, but if you commit yourself to it, you can do it. … because Wake doesn’t accept any students who can’t do it.”

Carol L. Hanner is a writer, book editor and former managing editor of the Winston-Salem Journal.