Perhaps unlike many Wake Forest graduates, Brock Jobe (’70) has had some of his most fascinating scholarly conversations while on the floor, studying the underpinnings of an Early American desk or chair. But like many of his fellow alumni, he credits a mentor for helping him get where he is today. In Jobe’s case the “where” is a celebrated career as professor and museum curator. And the mentor who pointed him in that direction was Wake Forest Professor of History Ed Hendricks.

'These objects have stories to tell,' says Brock Jobe.

“As a student in the late ’60s I hadn’t thought of a museum career; it hadn’t been understood or perceived that someone could be paid to do that kind of work,” said Jobe, who retired in 2015 as professor of American decorative arts at Winterthur, an estate, museum and library in Delaware housing one of the most important collections of Americana in the United States.

“I had an extraordinary experience with Dr. Hendricks in his colonial American history course. He got me interested in early history, and I had the chance to visit Old Salem and enjoyed that,” said Jobe, who earlier this year received the Eric M. Wunsch Award for Excellence in the American Arts, presented at Christie’s in New York City. “It paved the way for what eventually became a career.”

After a five-week course in all things early American — specifically household items — Jobe was hooked.

Jobe, who met his wife, Barbara (’70), at Wake Forest, was a newly married junior who knew nothing about Winterthur when Hendricks tipped him off to a graduate program there offered in conjunction with the University of Delaware. The opportunity interested him because it fused early American history, craft and art. It also had a major selling point for a newlywed: a full scholarship and stipend. He applied and was accepted.

“I didn’t fully grasp exactly what kind of program it was,” said Jobe, the oldest of three sons who are all Wake alumni. “I came into the program with very little understanding of historic American craft. I knew nothing about antique furniture, early glass, ceramics or silver.” After a five-week crash course in all things early American — specifically household items, he was hooked.

Brock Jobe and his wife, Barbara, met at Wake Forest and were married between their sophomore and junior years.

At the University of Delaware, where he earned a master’s degree from the Winterthur Program in Early American Culture in 1975, he worked with another mentor, Winterthur instructor Benno Forman. “I just found him to be inspiring,” said Jobe. “He took to me and got me hooked on furniture.” That experience led to a career and research focusing on objects made and used in New England.

After finishing his graduate work at Winterthur, Jobe began his career at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. His fascination with furniture would lead him to positions at Colonial Williamsburg, as the curator of exhibition buildings, and Historic New England (formerly Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities), where he was chief curator. In 1993 he returned to Winterthur as the deputy director for collections and interpretation. In 2000, he transitioned into his role as professor of decorative arts.

Keenly interested in the craft of building furniture, Jobe likes to look at every surface and every part, especially those not visible from afar. “I like to pull those drawers out, look inside the carcass and see how it’s made,” he said. “These objects have stories to tell.” One of his greatest challenges, but also greatest pleasures, in working with items people have left behind is the opportunity to tease out those stories and share them with others. “Facts can be as dry as toast, but folding information into a story brings it alive. We find those stories and craft them in such a way to be enjoyed and become meaningful to the public.”

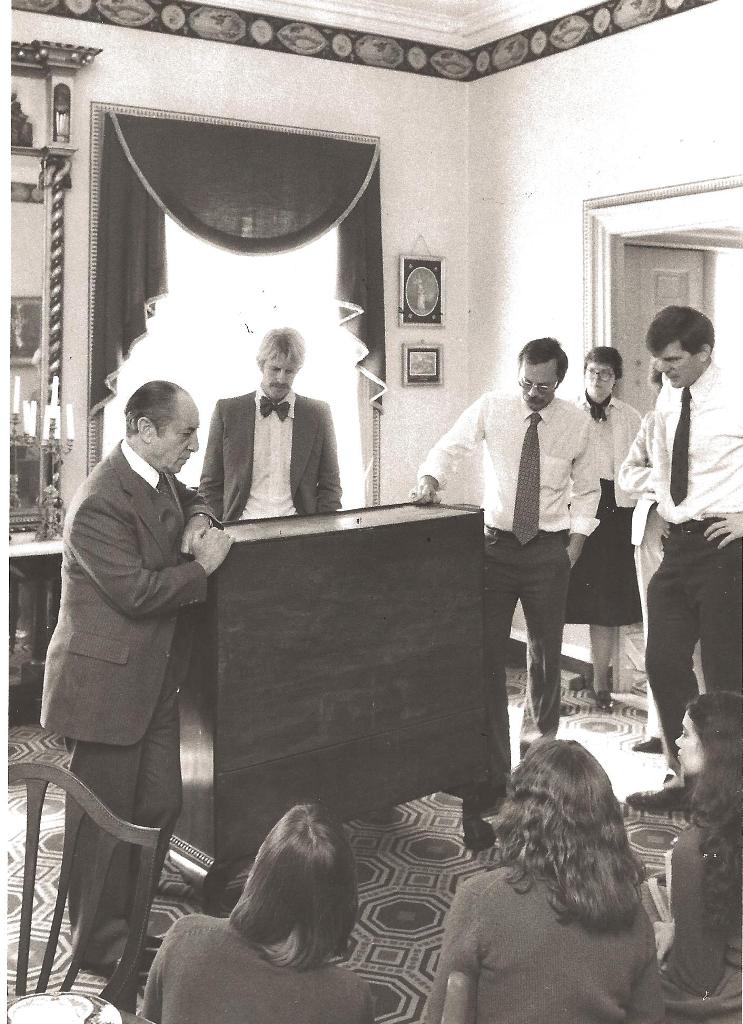

'I like to pull those drawers out, look inside the carcass and see how it’s made,' says Jobe, far right.

“Brock, in particular, is understood to have open arms to discourse on furniture, and I always enjoy photographs of him studying a piece because you can see in the look on his face that he loves what he is doing and that the table, chest, desk is about to get flipped upside down so he can feel, touch, embrace the object and soak in all that it is,” said Wunsch Americana Foundation President Peter Wunsch. “We are so happy to be able to honor a scholar of, and lover of, furniture like Brock Jobe.”

“At no time have I ever known Brock Jobe to be too busy, too engulfed or too self-absorbed to stop everything and advise a student, a colleague, a collector or a friend,” said Tom Savage, Winterthur director of museum affairs. “He counts among his devoted fans dealers, auctioneers, collectors, curators, conservators, all of whom admire him tremendously.”

Brock Jobe (far right) with (from left) Albert Sack, Gib Vincent, Richard Nylander, and Jayne Stokes, in the parlor of the Harrison Gray Otis House in Boston, mid-1980s.<br />

Jobe, who said with a chuckle that he has “failed retirement,” lives six miles from Winterthur and remains active there, studying, writing and lecturing about American furniture. He is a trustee for Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts, helping to interpret history through its buildings.

As a teacher and historian, he is especially pleased the village is beginning a charter school that will teach all manner of subjects. “What we used to call civics,” he said, “is just a basic understanding of how our country was formed, the various issues we’ve faced, how we’ve dealt with these issues — in some cases wisely and not so wisely — we have to make the next generation aware of that. All of us have to do what we can to include history in our curriculum and recognize the value of it. Maybe it will not provide you with a job, but it will provide you with a way of thinking that will provide you with more than a job.”