HERMAN EURE HAS FIRE AND ICE IN HIS VEINS, and BOTH HAVE SERVED HIM WELL.

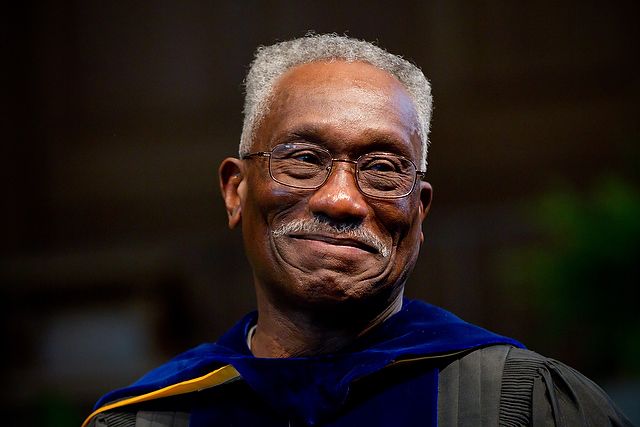

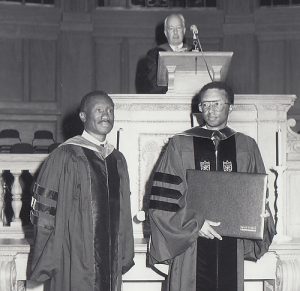

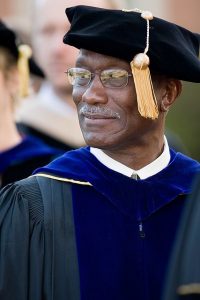

The ice steeled him for his journey through the 1960s and ’70s as a student leader in civil rights, as Wake Forest’s first full-time black graduate student, its first black doctoral recipient on the Reynolda Campus and its first black full-time faculty member. With unflappable demeanor, he moved past others’ doubts and initiated Wake Forest’s Office of Minority Affairs (now the Intercultural Center) in 1978. On Feb. 16, Eure received the University’s highest honor, the Medallion of Merit, to add to awards for his teaching and community service. In April he was elected to the University’s Board of Trustees, the first regular faculty member in modern times to have that role.

Under his cool resolve flows a fire of ambition, fueled by his parents’ relentless message that he could succeed at anything he wanted to do in this world. Anything. Befitting the scientist he would become, Eure could see concrete evidence that his parents, whose formal education ended at fifth and seventh grades, spoke the truth. He watched his oldest sister become the first in the family to attend college at what is now N.C. Central University in Durham, North Carolina. Ella Eure-Eaton went on to sing with the Metropolitan Opera in New York City.

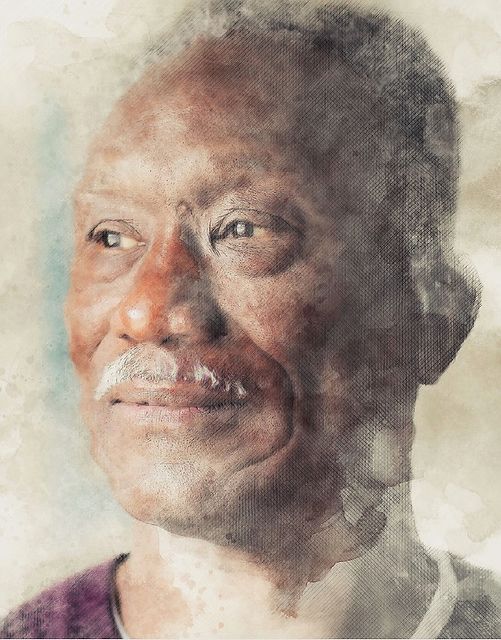

Herman Eure (Ph.D. '74), Medallion of Merit winner and scientist who led the way.

“I was never afraid,” said Eure (he adopted the more common pronunciation of “YOU-ree,” though back home it’s pronounced “Yewr”). “People used to say, ‘He’s cocky.’ It wasn’t cockiness; it was confidence. My father would make us prepare. If we were digging a ditch, do it the right way or don’t do it.”

“I was never afraid,” said Eure (he adopted the more common pronunciation of “YOU-ree,” though back home it’s pronounced “Yewr”). “People used to say, ‘He’s cocky.’ It wasn’t cockiness; it was confidence. My father would make us prepare. If we were digging a ditch, do it the right way or don’t do it.”

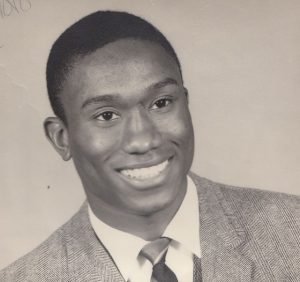

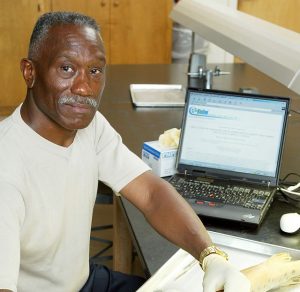

Eure, the seventh of 10 children growing up in the small northeastern North Carolina town of Corapeake, in Gates County, excelled at math and science as well as football, basketball and track.  He graduated as valedictorian and student leader at his segregated high school and accepted academic and track scholarships to the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, a historically black college. He went on to build a successful, rewarding career as a parasitologist, researcher, teacher and administrator, including chairman of the biology department and associate dean of the college at Wake Forest. Eure, 70, retired in 2013 to travel and enjoy time with his family – his wife, Kelli Sapp (MS ’93), who teaches biology at High Point University, two children and seven grandchildren.

He graduated as valedictorian and student leader at his segregated high school and accepted academic and track scholarships to the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, a historically black college. He went on to build a successful, rewarding career as a parasitologist, researcher, teacher and administrator, including chairman of the biology department and associate dean of the college at Wake Forest. Eure, 70, retired in 2013 to travel and enjoy time with his family – his wife, Kelli Sapp (MS ’93), who teaches biology at High Point University, two children and seven grandchildren.

Eure’s story is infused with several principles. Find mentors, listen to them and become a mentor to others. Do the work and be prepared. Believe in yourself. “My feeling was that what I think about me is more important than what you think about me,” Eure said. “Rooting my feelings about me in you is like being on a roller coaster, and I don’t like roller coasters.”

Eure’s story is infused with several principles. Find mentors, listen to them and become a mentor to others. Do the work and be prepared. Believe in yourself. “My feeling was that what I think about me is more important than what you think about me,” Eure said. “Rooting my feelings about me in you is like being on a roller coaster, and I don’t like roller coasters.”

He instilled confidence in his students while accepting no excuses for not trying. “You may not be able to do something as well as someone else, but if you commit yourself to it, you can do it … because Wake doesn’t accept any students who can’t do it.”

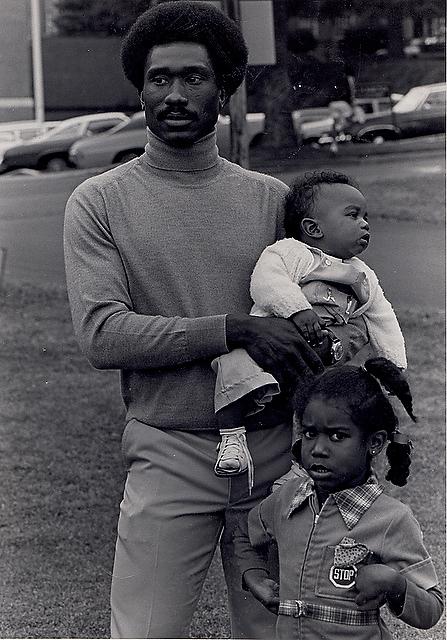

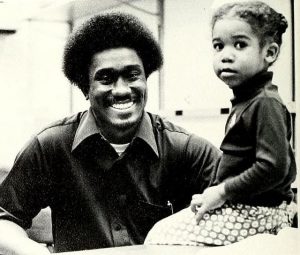

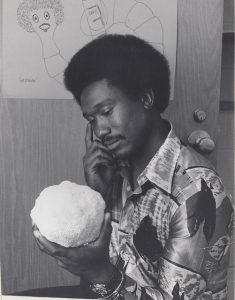

Herman Eure with his children, Lauren and baby Jared, in 1976.

One of the most important things that happened to him in high school, Eure said, was having his math teacher scare the heck out of him as he was about to graduate.

“He said, ‘Eure, more valedictorians flunk out of school than anyone else.’ What he was saying to me was, ‘You’re smart, but because you think you’re smart, don’t go to school not putting in the time and the work.’ He put me on notice.”

At college, Eure discovered that his athletic scholarship consisted primarily of a guarantee of a work-study job. If he had to work anyway, he would focus on academics. He never ran a day of track for the school. He loved both history and science, but science won out.

He once again excelled at academics and leadership, organizing civil rights demonstrations. He worked all kinds of jobs on campus, from cutting grass to assisting the president’s secretary, who gave him the application that landed him a prestigious Ford Foundation Fellowship for graduate school. He applied to three universities, but Wake Forest, which was starting a graduate program in biology, was his first choice. He and a brother drove to campus, and Eure spoke with Gerald Esch (P ’84), who was chairman of the biology department’s graduate committee.

He once again excelled at academics and leadership, organizing civil rights demonstrations. He worked all kinds of jobs on campus, from cutting grass to assisting the president’s secretary, who gave him the application that landed him a prestigious Ford Foundation Fellowship for graduate school. He applied to three universities, but Wake Forest, which was starting a graduate program in biology, was his first choice. He and a brother drove to campus, and Eure spoke with Gerald Esch (P ’84), who was chairman of the biology department’s graduate committee.

Esch said he told the young man who showed up at his door in 1969 that the department had no money left to pay him as a teaching assistant, which most graduate students needed to pay their bills. “Eure looked at me kind of funny and said he didn’t need any money. He said, ‘I have a Ford Foundation Fellowship for five years.’ ”

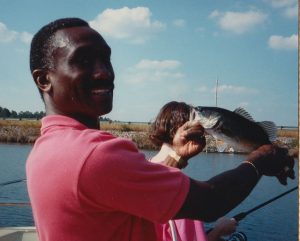

Eure wanted to be a parasitologist, and that was Esch’s specialty, too. The deal was sealed. With Esch’s help, Eure went straight to doctoral study, skipping a master’s degree but taking all the courses for both degrees. Esch helped Eure and another student do research at the Savannah River Ecology Laboratory at the nuclear site in Aiken, South Carolina. Eure studied parasites in largemouth bass.

Eure wanted to be a parasitologist, and that was Esch’s specialty, too. The deal was sealed. With Esch’s help, Eure went straight to doctoral study, skipping a master’s degree but taking all the courses for both degrees. Esch helped Eure and another student do research at the Savannah River Ecology Laboratory at the nuclear site in Aiken, South Carolina. Eure studied parasites in largemouth bass.

"I was 27 years old, with the big Afro, the bell-bottom pants. There were some kids who didn't quite know how to take me. Thought I was biased."

Wake Forest Medallion of Merit

Wake Forest Medallion of Merit

University Trustee

Donald O. Schoonmaker Faculty Award

Donald O. Schoonmaker Faculty Award

for Community Service

First faculty member

First faculty member

to deliver Founders’ Day address

Jon Reinhardt Award

Jon Reinhardt Award

for Distinguished Teaching

The inaugural Trident Professor Award

The inaugural Trident Professor Award

from the Gamma Kappa Chapter of

Delta Delta Delta

As Wake’s only black graduate student, Eure said he encountered bias, more often from staff who thought he should stick to his own kind. Students and faculty would ask whether he played basketball or football, assuming he must be an athlete. He experienced nothing but support in the biology department. Two older white Southern faculty members treated him with more respect than he had ever encountered in segregated eastern North Carolina. “These two didn’t care what I was as long as I did the work,” Eure said. “Look, you could have dropped my GRE (test) scores on the floor, and they would have sat right on the floor and wouldn’t wriggle, but I had great grades, great letters and, after my first year there, no one doubted that I could do the work.”

Failure was not an option, Eure said. How could he go home to Corapeake and say he hadn’t succeeded with this big opportunity?

Failure was not an option, Eure said. How could he go home to Corapeake and say he hadn’t succeeded with this big opportunity?

Eure said he was direct and sometimes angry at injustice, but he learned to modulate. “I figured out if you’re the loudest voice all the time, people know what you’re going to say and they avoid you. Keep your mouth shut sometimes.”

When Eure finished his doctorate in 1974 he had faculty job offers elsewhere and initially said no to Wake Forest, ready to try someplace new. But he saw what was possible at Wake Forest, and he knew he could make a difference. He stayed because of three men committed to progress: Provost Ed Wilson (’43), President James Ralph Scales and Dean of the College Tom Mullen (P ’85, ’88).

Mullen said he worked hard to recruit Eure.

Mullen said he worked hard to recruit Eure.

“I was most favorably impressed the first time I met him,” Mullen said. “For one thing, here is a man of great emotional balance and maturity. I’m talking about somebody before he’s begun teaching or had much experience in the academic world.”

Eure always worked hard, was a gifted teacher and successfully recruited many sought-after black students being courted by better-known universities, Mullen said. “Here is someone who had about him a sense of fairness, of being fair to colleagues, staff, students, willing to be of help to the people with whom he worked,” Mullen said.

“It’s fair to say he saw it through,” Mullen said. “Maybe that’s what a person does to become worthy of a Medallion of Merit. They see it through. They commit to the University. He certainly did that wonderfully well.”

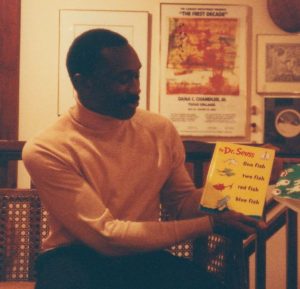

Eure was surprised by his experiences as the first black faculty member. (The late Dolly McPherson arrived in the English department the same year). “In my naïve way, I thought, ‘Well, I’m going to be the savior for black students.’ Because I knew the black kids had pushed to get minority faculty,” Eure said. But he found his greatest immediate impact was changing the expectations of white students, most of them facing a black teacher for the first time.

Eure was surprised by his experiences as the first black faculty member. (The late Dolly McPherson arrived in the English department the same year). “In my naïve way, I thought, ‘Well, I’m going to be the savior for black students.’ Because I knew the black kids had pushed to get minority faculty,” Eure said. But he found his greatest immediate impact was changing the expectations of white students, most of them facing a black teacher for the first time.

“I was 27 years old, with the big Afro, the bell-bottom pants,” Eure said. “There were some kids who didn’t quite know how to take me, thought I was biased. I said, ‘If you do the work, you can be green. You’ll get the grade that you earn.’ It never crossed my mind that I would grade someone down because they didn’t like me, because I knew I couldn’t afford to do that. I knew that I had to be better at what I did and fair at what I did because I knew everybody was watching me. So the same mistakes that a newly minted white Ph.D. could make, I couldn’t make those same mistakes.”

He counseled many black students and would tell them if they were wrong. He recalled a student angry that his English professor thought he had plagiarized a paper. Eure pointed out that the student’s black slang created a disconnect for the professor. “I told him, ‘I know as much (b.s.) lingo as you, but when I go to class, it’s the King’s English. Tell her to give you a topic to write on, sit in front of her and write it,’ ” he advised.

He counseled many black students and would tell them if they were wrong. He recalled a student angry that his English professor thought he had plagiarized a paper. Eure pointed out that the student’s black slang created a disconnect for the professor. “I told him, ‘I know as much (b.s.) lingo as you, but when I go to class, it’s the King’s English. Tell her to give you a topic to write on, sit in front of her and write it,’ ” he advised.

He also counseled faculty and staff who weren’t sure how to deal with black students. He challenged assumptions that black students would be C students, yet he also noted that not all issues with black students were black issues. He recommended that a teacher consider whether he or she would do the same whether the student was black or white.

He also counseled faculty and staff who weren’t sure how to deal with black students. He challenged assumptions that black students would be C students, yet he also noted that not all issues with black students were black issues. He recommended that a teacher consider whether he or she would do the same whether the student was black or white.

Eure pitched the idea of an Office of Minority Affairs to Provost Wilson in 1977. Some opponents noted that there was no Office of White Affairs. Eure argued that all offices were there for the majority and that the University wasn’t living up to its Pro Humanitate motto. Wilson created the office in 1978.

Minority enrollment data at Wake Forest weren’t available for 1974, but minority students have increased from 11 percent of the 3,624 undergraduates in 1992 to 29 percent this academic year, with black students accounting for 6.5 percent of the 4,955 students enrolled in fall 2016, according to the Office of Admissions. Black representation was 3.3 percent of the 451 faculty members in 2015, the most recent year available.

Minority enrollment data at Wake Forest weren’t available for 1974, but minority students have increased from 11 percent of the 3,624 undergraduates in 1992 to 29 percent this academic year, with black students accounting for 6.5 percent of the 4,955 students enrolled in fall 2016, according to the Office of Admissions. Black representation was 3.3 percent of the 451 faculty members in 2015, the most recent year available.

"Every student is different, and you have to figure out how to tap into that, to get them to give you what is there."

Susannah Sharpe Cecil (’90), who graduated in the Health and Exercise Science program and lives in Clemmons, North Carolina, said Eure was her favorite professor. “He was incredibly thorough, very fair, but also quite accessible. It was important to him that you got what he was trying to impart. He was a mentor, and he wanted his students to do well. He had such a good sense of humor. As a man, as a human being, he just showed great character and was very inspiring.”

For Eure, the most meaningful awards have come from his colleagues and students. “I never expected to win the Medallion of Merit. In some ways it’s kind of embarrassing to be given an award for doing something that you knew you should be doing anyway. For me being a college professor is a whole lot more than being in the classroom and doing research. You’re a mother, a father, a coach, a mentor, a cajoler, the person who has to crack the whip. You’re all those things. Every student is different, and you have to figure out how to tap into that, to get them to give you what is there. I’ve been really happy for students when I see the light turn on.”

For Eure, the most meaningful awards have come from his colleagues and students. “I never expected to win the Medallion of Merit. In some ways it’s kind of embarrassing to be given an award for doing something that you knew you should be doing anyway. For me being a college professor is a whole lot more than being in the classroom and doing research. You’re a mother, a father, a coach, a mentor, a cajoler, the person who has to crack the whip. You’re all those things. Every student is different, and you have to figure out how to tap into that, to get them to give you what is there. I’ve been really happy for students when I see the light turn on.”

Carol L. Hanner is a writer, book editor and former managing editor of the Winston-Salem Journal. Historian Jim Barefield also received the Medallion of Merit this year. Read Joy Goodwin’s (’95) profile of him, “Seriously Funny,” from our summer 2012 issue.