Dr. Atala, director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, added to his long list of professional accolades when in November Smithsonian Magazine named him the winner of the 2016 American Ingenuity Award for Life Sciences and R&D Magazine named him 2016 Innovator of the Year. In April he won the health category of Fast Company’s 2017 World Changing Ideas Awards. Dr. Atala has led scientists who were the first to create and successfully implant a laboratory-grown organ — a bladder — into patients. A pediatric surgeon and the University’s W.H. Boyce Professor and Chair of Urology, Dr. Atala is a pioneer in growing human cells, tissues and organs using 3-D printing technologies. He leads a team of 450 at the Institute. Following is a sampling of his comments over the years about his path-breaking work, which continues to garner international acclaim.

Dr. Atala, director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, added to his long list of professional accolades when in November Smithsonian Magazine named him the winner of the 2016 American Ingenuity Award for Life Sciences and R&D Magazine named him 2016 Innovator of the Year. In April he won the health category of Fast Company’s 2017 World Changing Ideas Awards. Dr. Atala has led scientists who were the first to create and successfully implant a laboratory-grown organ — a bladder — into patients. A pediatric surgeon and the University’s W.H. Boyce Professor and Chair of Urology, Dr. Atala is a pioneer in growing human cells, tissues and organs using 3-D printing technologies. He leads a team of 450 at the Institute. Following is a sampling of his comments over the years about his path-breaking work, which continues to garner international acclaim.

— Maria Henson (’82)

“Some people point to eureka moments, either with discovery or accomplishments, but the fact is that everything we do is long and laborious before we actually get results. Of course, every time you get good results you feel good because you’re one step closer to helping a patient. And that’s always rewarding.”

— Class Notes, Miami Magazine, Spring 2004

“And when we launch these technologies to patients we want to make sure that we ask ourselves a very tough question. Are you ready to place this in your own loved one, your own child, your own family member, and then we proceed. Because our main goal, of course, is first, to do no harm.”

— at TEDMED, October 2009

“I don’t know if you realize this, but 90 percent of the patients on the transplant list are actually waiting for a kidney. Patients are dying every day because we don’t have enough of those organs to go around. So this is more challenging — large organ, vascular, a lot of blood vessel supply, a lot of cells present. So the strategy here is — this is actually a CT scan, an X-ray — and we go layer by layer, using computerized morphometric imaging analysis and 3-D reconstruction to get right down to those patient’s own kidneys. We then are able to actually image those, do 360-degree rotation to analyze the kidney in its full volumetric characteristics, and we then are able to actually take this information and then scan this in a printing computerized form.

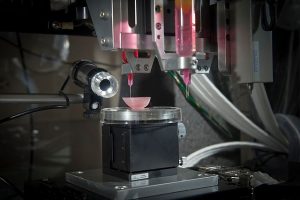

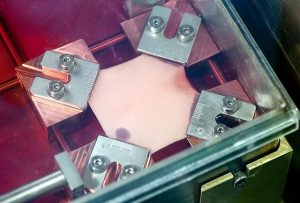

“I don’t know if you realize this, but 90 percent of the patients on the transplant list are actually waiting for a kidney. Patients are dying every day because we don’t have enough of those organs to go around. So this is more challenging — large organ, vascular, a lot of blood vessel supply, a lot of cells present. So the strategy here is — this is actually a CT scan, an X-ray — and we go layer by layer, using computerized morphometric imaging analysis and 3-D reconstruction to get right down to those patient’s own kidneys. We then are able to actually image those, do 360-degree rotation to analyze the kidney in its full volumetric characteristics, and we then are able to actually take this information and then scan this in a printing computerized form.  So we go layer by layer through the organ, analyzing each layer as we go through the organ, and we then are able to send that information, as you see here, through the computer and actually design the organ for the patient. This actually shows the actual printer. And this actually shows that printing.”

So we go layer by layer through the organ, analyzing each layer as we go through the organ, and we then are able to send that information, as you see here, through the computer and actually design the organ for the patient. This actually shows the actual printer. And this actually shows that printing.”

— “Printing a human kidney” TED talk, during which he printed a kidney-shape “mold” made of cells, March 2011

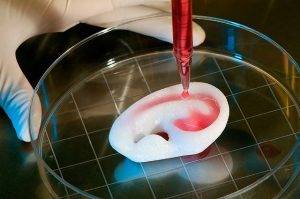

“The field was started where you use the patients’ own cells where you take a very small tissue, less than half the size of a postage stamp, of the tissue of interest from the same patient. You then expand those cells outside the body from that piece of tissue. You grow the cells in an incubator, create a 3-dimensional mold, if you will, using artificial materials that are degradable over time. …

“The field was started where you use the patients’ own cells where you take a very small tissue, less than half the size of a postage stamp, of the tissue of interest from the same patient. You then expand those cells outside the body from that piece of tissue. You grow the cells in an incubator, create a 3-dimensional mold, if you will, using artificial materials that are degradable over time. …  We then place those cells on these structures, allow them to mature and then we implant them back into the patient. … The printer is just really a way to scale it up.”

We then place those cells on these structures, allow them to mature and then we implant them back into the patient. … The printer is just really a way to scale it up.”

— “The Diane Rehm Show,” Dec. 18, 2014

“Wouldn’t it be great if we could basically just regenerate ourselves? Wouldn’t that be great? Well, is that science fiction?

Not really. Actually, one of the things that happens in nature is that things in fact can regenerate. This is the limb of a salamander, and this is real time-lapse photography, and you can see here the salamander limb fully regenerating after it was injured, within seven days. So the question, of course, is if a salamander can do it, why can’t we? And that’s really where this field comes in that we call regenerative medicine.”

Not really. Actually, one of the things that happens in nature is that things in fact can regenerate. This is the limb of a salamander, and this is real time-lapse photography, and you can see here the salamander limb fully regenerating after it was injured, within seven days. So the question, of course, is if a salamander can do it, why can’t we? And that’s really where this field comes in that we call regenerative medicine.”

— 37th annual Brown Symposium, Southwestern University, February 2015

“We’ve actually shown that we can print a broad range of tissues, from soft tissues such as muscle to medium-strength tissues such as cartilage, which are elastic, to strong tissues such as bone. So the concept now is to keep testing these tissues so we can get them into patients. … The concept is if a patient has a defect or an injury, you can do an X-ray of that area and then basically the X-ray shows the area of the defect and we can download that information digitally into our software program that drives the printheads and that actually will print a structure that will fit that patient using the patient’s own cells.”

“We’ve actually shown that we can print a broad range of tissues, from soft tissues such as muscle to medium-strength tissues such as cartilage, which are elastic, to strong tissues such as bone. So the concept now is to keep testing these tissues so we can get them into patients. … The concept is if a patient has a defect or an injury, you can do an X-ray of that area and then basically the X-ray shows the area of the defect and we can download that information digitally into our software program that drives the printheads and that actually will print a structure that will fit that patient using the patient’s own cells.”

— CNN, February 2016

An editorial in the Winston-Salem Journal on Dec. 15, 2016, called Dr. Atala “a gentleman we consider one of our greatest local talents.”