In 1979, when art department chair Robert “Bob” Knott was recruiting me to move to Winston-Salem and Wake Forest, he kept saying, “Reynolda House is in our backyard.” I had never heard of Reynolda House and didn’t have a clue what he meant.

Bob and I had been colleagues at the University of Massachusetts-Boston and neighbors in Boston’s South End. A native of Memphis who had been educated in California, Illinois and Pennsylvania, Bob had returned south in 1976 to teach modern art in the new art department that was taking shape at Wake Forest, and he wanted me to join him. I was an art historian, an “Americanist” focused on architectural history and historic preservation.

When I arrived in Winston-Salem for my requisite talk to University faculty and meetings with administrators, it was April. Those of you familiar with the Northeast know that April in Winston-Salem beats April in Boston by a mile. It isn’t even a race. For three days, I was never off Reynolda Road. I thought all of Winston-Salem looked like Reynolda Road in springtime.

The only other place I saw besides the University was the Reynolda House Museum of American Art. Bob took me there to meet Nick Bragg (’58), its legendary director, who had attended my talk — an indication of the connection between Reynolda and the nascent art program at Wake Forest.

Harold W. Tribble Professor Emerita Margaret Supplee “Peggy” Smith

The museum was housed in tobacco magnate Richard J. Reynolds’ former home, an impressive white stucco bungalow with an astonishing green Ludowici tile roof. My grandparents lived in the Philadelphia suburb of Bala Cynwyd in a white stucco house with a green roof. The Reynolds home thus looked familiar to me, but, of course, it was infinitely grander.

I remember walking through the museum’s classically proportioned rooms, amazed at the quality of the paintings and aware that I could enjoy and teach works by Frederic Church, Thomas Hart Benton, Georgia O’Keeffe and other major American artists nearby, just through the woods — literally in our backyard.

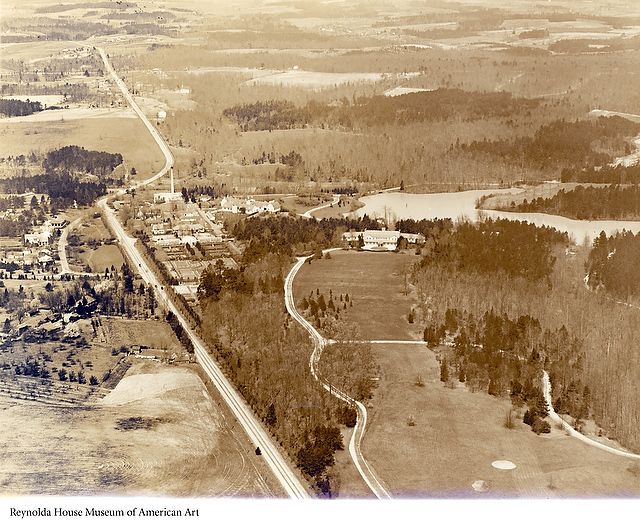

My “inner” historian compels me to clarify that the University is actually in Reynolda’s backyard, the distant pastures of the 1,067-acre estate that included a village; a school, church and post office; barns and other farm buildings; pastures, fields and a lake, as well as the impressive bungalow where the family lived.

Peggy Smith says the Reynolds estate “was a point of pride for local people.”

I found the domestic setting of the museum welcoming. Outside, the gardens sparkled with weeping cherry and dogwood trees; hundreds of daffodils animated the woods. Lake Katharine had some water in it in those days. Bob sold me on making the move, leaving the slushy streets of Boston in spring behind.

In the intervening years, my first impressions of Reynolda have held firm. I have relished the opportunity to view the extraordinary art, study the estate’s architecture and enjoy its landscapes. In the years I was still a runner, I jogged through the woods and around the lake, Sony Walkman in hand, frequently passing by biology Professor Herman Eure (Ph.D. ’74) and his physically fit cohorts from the athletics department. On a professional level, many of my research projects have originated from the estate, its architecture and its occupants.

When the Reynolds family built Reynolda (1912-17), there was nothing like it in North Carolina. Biltmore in Asheville was larger and grander, but George Vanderbilt was an outsider, not born and bred in tobacco country. Katharine Smith Reynolds hailed from Mount Airy, just up the road, and R.J. Reynolds came from just across the border in Virginia. When he founded America’s most successful tobacco company in Winston-Salem (and kept the stock local so the money stayed here), he ushered in an era of prosperity unmatched in the history of a small Southern city.

The Reynolds estate was a point of pride for local people. They read about it in the newspaper, they rode out Reynolda Road to see it, and no doubt they discussed the comings and goings of the Reynolds family in endless detail.

Katharine Reynolds envisioned Reynolda’s landscape as a beautiful setting that extended the estate and its buildings into nature. It provided places for her children, family and friends to swim, go boating, play tennis, hit golf balls or hike in the woods. The landscape also served the community. The gardens were located along Reynolda Road so that locals could enjoy the trees and flowers. Nearby farmers learned from its model farm and up-to-date technology.

(In the 1980s, as Wake Forest embraced women’s studies, the insights of that discipline helped reshape Reynolda’s historic identification with the tobacco manufacturer to include his young wife, Katharine, and her progressive vision of a model farm, diversified agriculture, education reform, healthy recreation and suburban living. Katharine Reynolds became the centerpiece of the museum’s first exhibition on its history as an American country house, and the feminine “Reynolda” acquired a whole new meaning).

As Reynolda’s landscape has matured and the surrounding area become more densely settled, its importance to the community for recreation and respite has become even more apparent. I like to think about Wake Forest as part of the historic landscape of Reynolda: a chapter started in the 1950s.

From the air and on the ground, Reynolda is the gemstone of Winston-Salem’s “Emerald Necklace” which encompasses the University, Reynolda, Graylyn and the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art (SECCA).

The museum was created 50 years ago by Reynolds children and grandchildren as a way to ensure Reynolda’s continued relevance to the community, and hence, its preservation. R.J. and Katharine Reynolds’ daughter Mary worried about how the estate could sustain itself; her husband, Charles Babcock (LL.D. ’58), and daughter Barbara saw an art museum as a way to preserve its importance to the community and ensure its viability. Drawing on her Smith College training as an art historian, Barbara Millhouse (L.H.D. ’88, P ’02) assembled a major American art collection in the 1960s.

Generations of art majors have felt that Reynolda belonged to them, but the collection has been important for everyone who loves art. Now, as Amy E. Herman, who has worked with police, lawyers, doctors and just about everyone else, writes in her book, “Visual Intelligence,” studying artworks can “sharpen your perception, change your life” by developing observation skills which can be transferred to life’s important challenges.

Generations of art majors have felt that Reynolda belonged to them, but the collection has been important for everyone who loves art. Now, as Amy E. Herman, who has worked with police, lawyers, doctors and just about everyone else, writes in her book, “Visual Intelligence,” studying artworks can “sharpen your perception, change your life” by developing observation skills which can be transferred to life’s important challenges.

As Reynolda celebrates its centennial, what more could we ask? And it is in our backyard.

Harold W. Tribble Professor Emerita Margaret Supplee “Peggy” Smith, a recipient of the University’s highest honor, the Medallion of Merit, retired in 2011 after 32 years at Wake Forest. Her most recent book is “American Ski Resort: Architecture, Style, Experience.”