Susan Payne Carter (’06) knew as an undergraduate that having her laptop in class could lure her onto AOL Instant Messenger, the communication of choice before iPhones, iPads, Twitter and Instagram became ubiquitous.

Later, she saw the impact of electronic devices in the college classes she teaches.

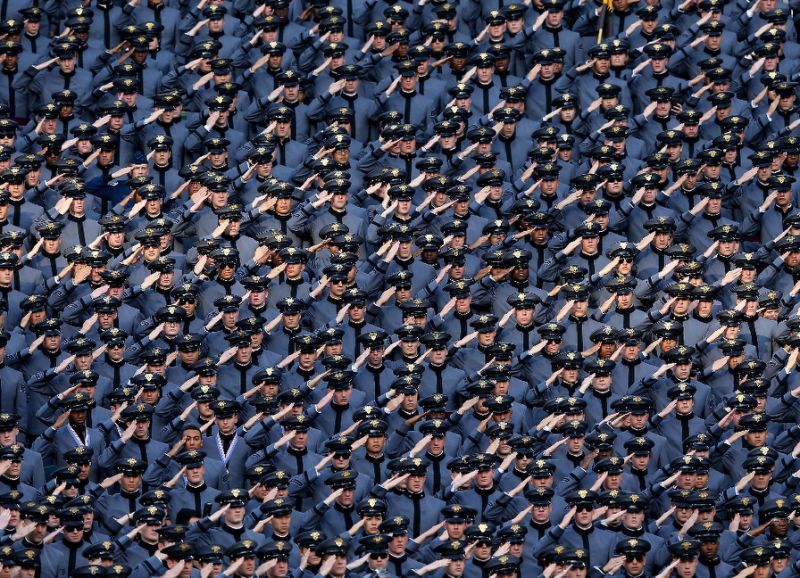

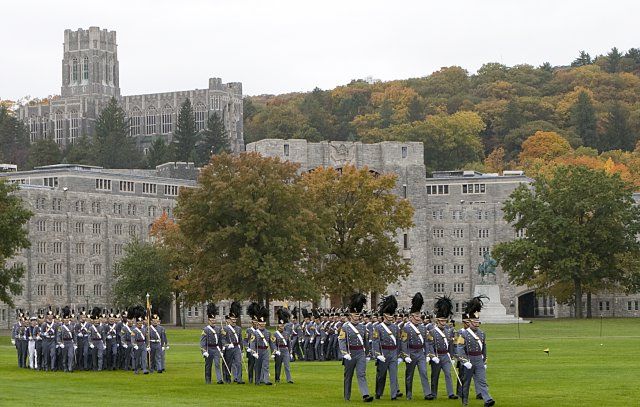

“I know personally I get distracted by using the computer, so as an instructor I often don’t let students use computers in class,” said Carter, an assistant professor at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and research analyst in its Office of Economic and Manpower Analysis.

Susan Payne Carter and her research colleagues found that use of computers and laptops in the classroom reduced students' final exam performance.

But is typing lecture notes more effective than writing them? Isn’t the internet a key tool in classrooms? Or does a device in hand distract from learning and prove that successful multitasking is an illusion? Or all of the above?

Some studies have focused on these topics, but questions remain. So when a colleague at West Point suggested that Carter ply her statistical trade on whether computers and tablets in class during the semester affected final exams, she was game.

The result was an experiment from 2014 to 2016 by Carter and colleagues Kyle Greenberg and Michael S. Walker. They found that computers and tablets in the classroom, even with strict limits on their use, reduced students’ average final-exam performance in a statistically significant way. The negative effects on final exams occurred even with the group that was allowed to use only iPads, which had to lie flat in view of professors.

Carter is an assistant professor at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and research analyst in its Office of Economic and Manpower Analysis.<br />

The effect of laptop and tablet use was large enough that it could make the difference between a B+ and an A-. In statistical terms, the difference was one-fifth of a standard deviation, or 1.7 percentage points on a 100-point scale. And this was true in the highly competitive environment of West Point, where grades affect later military job opportunities, giving students a strong incentive to pay attention.

Carter, originally from Houston, knows what it takes to succeed in academics. She graduated summa cum laude in mathematical economics at Wake Forest and received numerous honors, including the Wall Street Journal Student Achievement Award in Economics. In 2012, she was awarded a Ph.D. in economics from Vanderbilt University. At West Point, she received the Murdy Award for Teaching Excellence in the Department of Social Sciences in 2013.

She spoke to Wake Forest Magazine about the study. An edited version of the conversation is below. She said she’s obligated to note that she doesn’t represent the views of West Point, the Department of Defense or the U.S. Army.

What is your advice to an instructor trying to decide how to handle computers in the classroom?

Instructors probably are and they should just continue to be wary that if students are on their computers, they could be distracted, or it could be that people aren’t able to take notes as well. Our paper does not distinguish between those two, so we don’t know what the driving force is. (Some research shows hand-written notes are more effective, possibly because students focus on concepts instead of stenography.) Just be wary that there are potentially negative effects. And possibly (they should) inform their students of our study so the students can make their own decision.

Explain the significance of the variations in grades you found.

It amounts to a little bit less than 2 percentage points, a 72 versus a 74. The main point isn’t that their grade necessarily will be dramatically lower because we’re just looking at the objective portion of their final exam. (The study analyzed multiple choice and short answers that accounted for 85 percent of grades but not essay questions that were graded more subjectively.) We’re saying that their comprehension of the material is lower.

What did you find the most surprising or interesting aspect of your conclusions?

I thought it was interesting that allowing just the tablets had similarly negative effects to using the computer. The tablet can be used a little bit more like writing with paper and pen, although there are still distractions that come up — there are the messaging services and email just like on an iPhone. (The study found that 80 percent in the full technology classes used the technology during class while only 40 percent of the tablet-only students did.) Tablets are still relatively new for taking notes so it could also be that students are not as adept at taking notes on a tablet as they are on paper.

What has been the response from instructors?

What I found is that there are a number of instructors who now give this paper out at the beginning of class. To me it’s fun that instructors are actually using our study to inform their students of the potential effects or using our study to justify not using computers in traditional classes. So it’s actually having an impact.

"I thought it was interesting that allowing just the tablets had similarly negative effects to using the computer,' says Susan Payne Carter.

What options do you see for avoiding distractions when a computer is necessary as part of instruction?

I’ve heard of classrooms where the internet is blocked, not at West Point. But you’re still typing, so if typing is causing you to have worse note-taking, then it would still be a negative effect. Perhaps more monitoring of students, which just becomes harder in larger classes. A nice aspect of West Point is that the classes are so small (averaging 15 students in the study) so the distraction effect should actually be smaller than in a classroom where you’re not so close to your instructor. Any sort of classroom technique that keeps students engaged would help.

There are all sorts of teaching techniques to keep students engaged, such as “clickers,” where an instructor will ask a question and all students are required to answer, and the answer will populate on the board.

What else should we be sure to take note of?

One of the biggest complaints we get from people who don’t really read our article is that we’re saying that all computers and technology are bad for learning, but that’s not what our study is showing. We’re saying that in the traditional classroom environment where laptops are optional we’re finding negative effects.

What’s next?

We’d like to dig more into what could be causing these negative effects of computer usage, whether it’s the distraction of email or other websites, teasing out that.

Susan Payne Carter says she has heard of classrooms where the internet is blocked, but not at West Point.

From a broader view, what drew you to study economics?

I took an econ class my freshman year, my first semester at Wake. I saw the applicability of economics in the first few lessons on such basic concepts as opportunity costs. It’s just a logical way of thinking, and I really enjoy that. I’ve always liked math and enjoyed doing calculus, and in economics I’m able to use my math in an applied way.

How has it been doing this work in a military environment?

It’s very exciting and interesting. I do more labor economics now, and we have good data on people in the military, and there’s just a lot of interesting policy-relevant questions you can ask.

Switching back to Wake Forest, what is your favorite memory of your time there?

Non-academic? Three of my favorite nights were in my freshman, sophomore and junior years when we beat Duke in basketball and we went to wrap the Quad. It was exciting.

The full published study is here in the February 2017 issue of Economics of Education Review.

Carol L. Hanner is a writer, book editor and former managing editor of the Winston-Salem Journal.